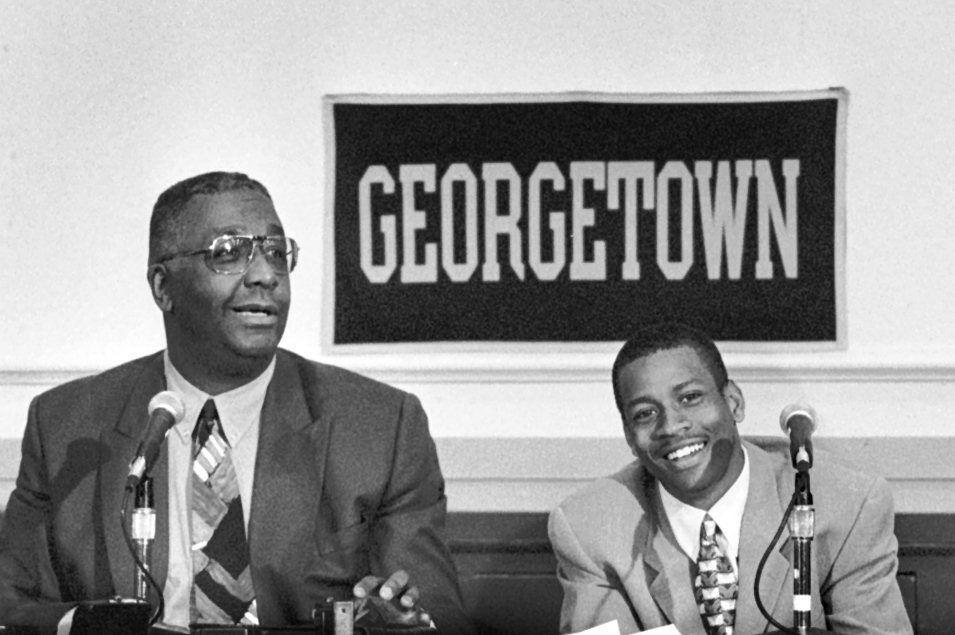

John Thompson, coach who built Georgetown basketball into national power, dies at 78

Physically imposing at 6-foot-10 and nearly 300 pounds and possessed of a booming bass voice that commanded authority better than a shrill whistle could, Mr. Thompson built his teams around similarly intimidating centers such as Patrick Ewing, Dikembe Mutombo and Alonzo Mourning and a physical, unrelenting approach to defense.

His most profound contribution to the game was his grasp of its power to lift disadvantaged youngsters to a better life. He used college basketball — and his stature in the sport — as a platform from which to demand greater opportunities for Black athletes to gain the college education they might otherwise have been denied.

To Mr. Thompson, a basketball scholarship was a vehicle rather than a destination.

For a youngster like himself, reared in racially segregated Southeast Washington and labeled academically challenged because of undiagnosed vision problems, basketball was a door that led to opportunity.

After a standout career as a center at Archbishop Carroll High School, he went on to graduate from Providence College in Rhode Island with a degree in economics. Later, after a two-year career in the National Basketball Association, he earned a master’s degree in guidance and counseling at the University of the District of Columbia.

Basketball-as-opportunity was a cause Mr. Thompson championed throughout his career. When the National Collegiate Athletic Association in 1989 adopted a proposition that would deny financial aid to recruits who failed to meet minimum scores on standardized college-admission tests, Mr. Thompson boycotted two of his own team’s games in protest.

As for the sport itself, Mr. Thompson likened it to a fantasy, using the metaphor of a deflated basketball to drive home to his players what their life would ultimately consist of if they didn’t plan for a future beyond the game.

“Don’t let eight pounds of air be the sum total of your existence” was Mr. Thompson’s frequent refrain, and the cautionary words were displayed in the lobby of Georgetown’s McDonough Arena, where Hoya teams continued to practice well after he stepped down from coaching in 1999.

Though he reached the pinnacle of his profession in leading Georgetown to the 1984 NCAA championship with an 84-75 victory over Houston, Mr. Thompson bristled at being referred to as the first Black coach to do so — not because he minimized the achievement, but because he felt that claiming the label slighted generations of African American coaches who could have accomplished the same had they only been given the chance.

On the local level, Mr. Thompson transformed a moribund basketball program at Georgetown into one of the nation’s most prestigious, compiling a 596-239 record during his 27-year tenure. Along the way, he broke down barriers between the Jesuit institution in Northwest Washington, long regarded as an exclusive, cloistered enclave, and the predominantly African American city at large.

“Coach Thompson should get more credit than he gets for having created diversity at Georgetown, connecting Georgetown to this city and making it clear that Georgetown is not some elite institution sitting off there on the top of a hill,” former NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue, captain of Georgetown’s 1961-1962 basketball team, told The Washington Post.

On a national level, Mr. Thompson was a key figure in launching the Big East Conference in 1979. The league, which was long dominated by Mr. Thompson and other coaches such as Jim Boeheim of Syracuse, Jim Calhoun of Connecticut and Rollie Massimino of Villanova, was defined by its often bitter, always passionate basketball rivalries.

Six words kick-started the blood feud in the Big East’s inaugural season. They were uttered Feb. 13, 1980, by Mr. Thompson during the news conference that followed Georgetown’s 52-50 upset of No. 2-ranked Syracuse in the final planned, regular-season game at Manley Field House, where the Orange boasted a 57-game winning streak. Georgetown trailed by 14 at halftime, but with five seconds remaining, the Hoyas’ Sleepy Floyd hit the free throws that won the game.

“Manley Field House is officially closed,” Mr. Thompson famously intoned.

Decades later, as Syracuse prepared to leave the Big East for the Atlantic Coast Conference, Boeheim reflected on the intensity of the rivalry and his affection for Mr. Thompson.

“There was never a moment in a Syracuse-Georgetown game that somebody took a play off,” Boeheim told The Post. “There were 10 people on the court playing every play; the coaches were coaching every play. We’ve had great games with a lot of teams, but the games you remember are Syracuse-Georgetown.”

With the Hoyas’ 1984 NCAA championship, Mr. Thompson turned Georgetown basketball into a brand that was recognized worldwide, as well as a symbol of pride for countless urban youths throughout the country.

Mr. Thompson achieved much of his success by fighting against the grain. He reveled in standing up, speaking out and challenging the establishment when it came to causes he believed in. For this, he was criticized from all sides during his coaching career.

Whites faulted him for fielding all-Black squads. Many Blacks faulted him for not doing more for African Americans.

Fiercely loyal to his inner circle, Mr. Thompson trusted few in the coaching fraternity and even fewer journalists. The secrecy with which he shrouded his players was often interpreted as evidence that Georgetown basketball had something to hide. It gave rise to a media-coined diagnosis, “Hoya Paranoia,” that Mr. Thompson particularly disliked.

Other coaches charged that Georgetown, under Mr. Thompson, was prone to rough play and fighting. One brawl with the University of Pittsburgh had to be broken up by police.

Much like his teams, Mr. Thompson had a game-day persona that could be intimidating. He patrolled the sideline with a signature white towel draped over his shoulder, rarely pleased with the proceedings. In a heated game against Syracuse in March 1990, with the Big East’s regular-season title at stake, Mr. Thompson was ejected after drawing three technical fouls in a 90-second span.

Asked in a 2013 interview what he recalled about the sequence of events, which included a thunderous foot stomp, a foray onto the court and at least one expletive, Mr. Thompson, who had mellowed with age, said with a laugh: “I don’t remember why I was mad. I probably created something to be mad about, to tell you the truth … I functioned better when I thought people didn’t like me than I did when I thought they did.”

Building a powerhouse

John Robert Thompson Jr. was born Sept. 2, 1941, in Washington and was enrolled in Catholic school by his mother, who believed he would benefit from the academic rigor. Unusually tall for his age, he was recruited to play basketball at Archbishop Carroll High School, which he led to three consecutive city championships, 55 straight victories and an undefeated season his senior year in 1960.

But Washington was a segregated city for much of his youth. Even in church, Mr. Thompson had to wait for White parishioners to finish their prayers before he could approach the altar.

He enrolled at Providence College, steered once again by his mother’s belief that the priests would look after her son, and led the Friars to the 1963 National Invitation Tournament title and, in 1964, their first NCAA tournament appearance.

On the heels of a stellar college career, setting school records for points, scoring average and field-goal percentage, Mr. Thompson was chosen by the Boston Celtics in the third round of the 1964 NBA draft — the year of his college graduation.

He primarily served as a backup to the Celtics’ star center, Bill Russell, during his two seasons in the NBA, in which Boston won back-to-back championships. Mr. Thompson, taking a cue from Russell, learned to keep a distance from the media and his rivals. Weary of the itinerant lifestyle, he chose to retire rather than relocate to Chicago, which chose him in the NBA’s 1966 expansion draft.

Returning to Washington, Mr. Thompson took a job as a guidance counselor and started coaching part time at St. Anthony High School, where his teams compiled a 122-28 record.

His hiring as Georgetown’s head coach represented a bit of a gamble. Despite having coached at the high school level just seven years, he was chosen over such more established candidates as Morgan Wootten and George Raveling.

Mr. Thompson insisted as a term of his employment that he be given latitude to recruit high school students who wouldn’t otherwise meet Georgetown’s rigorous admission standards. To ensure they had a bona fide chance at academic success, he also negotiated the right to hire Mary Fenlon, a former nun he had worked with at St. Anthony’s, to serve as the Hoyas’ academic coordinator. As a result, 75 of the 77 players who stayed at Georgetown for four years under Mr. Thompson received their degrees.

Mr. Thompson’s close watch on his players’ academic progress was just one aspect of the short rein he kept on his charges throughout their college careers. He required them to travel in coat and tie. He ordered 5 a.m. practices if a player skipped a class. His micromanagement of their lives was alternately criticized, praised and cited as cause for suspicion over the years.

When it came to basketball, Mr. Thompson insisted his players adhere strictly to the style of play he instructed, built on a foundation of relentless defense.

“I don’t coach their team,” Mr. Thompson famously declared. “They play on my team.”

He had stepped into a college coaching job that, at the time, was viewed as no spectacular prize. Georgetown’s record the season before Mr. Thompson was hired in 1972 was 3-23. But success soon followed.

Georgetown qualified for the NCAA tournament three seasons after Mr. Thompson took over. He led the Hoyas to 20 NCAA tournament appearances — including a streak of 14 years in a row — and six Big East tournament titles.

His most glorious run on the Hilltop, as the Georgetown campus is known, coincided with the Patrick Ewing era. When Ewing, a 7-foot center from Cambridge, Mass., enrolled at Georgetown in 1981, he catapulted the Hoyas to national prominence, prompting the team to play most of its games off campus at the more spacious Capital Centre in Landover, Md.

During Ewing’s freshman year, Mr. Thompson took his first Georgetown squad to the NCAA Final Four, where the Hoyas fell, 63-62, in the championship game to a North Carolina team that included future NBA stars Michael Jordan and James Worthy.

After defeating Houston for the 1984 NCAA title, Georgetown nearly repeated the following year but was toppled by eighth-seeded Villanova. Ewing, named the national college player of the year, became the No. 1 pick in the 1985 NBA draft.

Having been an assistant to North Carolina coach Dean Smith on the gold medal-winning U.S. basketball team at the 1976 Olympics, Mr. Thompson was named head coach of the U.S. Olympic squad that claimed bronze at the 1988 Summer Games in Seoul. It was the last time the United States would field an Olympic basketball team composed only of amateur players.

Mr. Thompson found less success with his Georgetown teams of the 1990s. In 1996, the talented but troubled Allen Iverson became the first Georgetown player under Mr. Thompson to leave school early, entering the NBA draft after his sophomore year.

As the stakes of recruiting ramped ever higher, he chafed at scouring the country in courtship of young phenoms, feeling the teens should be begging Georgetown to enroll them rather than the reverse.

Mr. Thompson’s resignation as Georgetown’s head coach was abrupt, submitted in January 1999, just as the Big East season was getting underway. He cited personal issues, which included a recent divorce from his wife of 32 years, the former Gwendolyn Twitty, his high school sweetheart.

Just 57 at the time, Mr. Thompson never coached again. Later that year, he was named to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. He remained a fixture on Georgetown’s sidelines as his eldest child, John Thompson III, took over the head coaching job in 2004 from Craig Esherick, the elder Thompson’s longtime assistant.

In 2007, Mr. Thompson and John Thompson III became the first father and son to coach in an NCAA Final Four. But in March 2017, the university fired the younger Thompson following the program’s first back-to-back losing seasons in 44 years, and named Ewing head coach.

Survivors include his three children, John Thompson III, Ronny Thompson and Tiffany Thompson; and several grandchildren.

Life after coaching

In his later years, Mr. Thompson parlayed his powerful voice and point of view into a career as a sports talk radio host, with “The John Thompson Show” airing on ESPN 980 (WTEM AM). Mr. Thompson also provided color commentary for national college basketball games on the Westwood One Sports network.

With the academic title of presidential consultant for urban affairs at Georgetown, Mr. Thompson maintained a modest office in McDonough Arena. Known as “Big Coach” to subsequent generations of Hoya players, Mr. Thompson attended closed-door practices led by his son and was a key figure through the years in the decisions of many standout players to enroll on the Hilltop.

In October 2016, Georgetown unveiled a state-of-the-art, 144,000-square-foot, on-campus athletics facility named in the former coach’s honor. Built at a cost of $62 million, the five-level John R. Thompson Jr. Intercollegiate Athletics Center houses indoor practice courts, offices (including one for Mr. Thompson) and an academic center for the university’s roughly 700 student-athletes. A bronze statue of the former coach stands near the entrance.

“My father never learned to read, never made anywhere near the kind of money I make, but he was a success. So was my mother,” Mr. Thompson told The Post in 1984. “I am perceived as a success by standards created by white people. My team wins a lot of games; I make a lot of money. When I’m 80 and look back, is that going to make me think of myself as a success? I don’t think so.

“But if I change some things, even slightly — if I stand up on this platform I’ve been given and say, ‘No, this is wrong,’ then maybe I will feel good about myself. I may not change anything, and I know I’m going to upset some people. But I can live with that.”