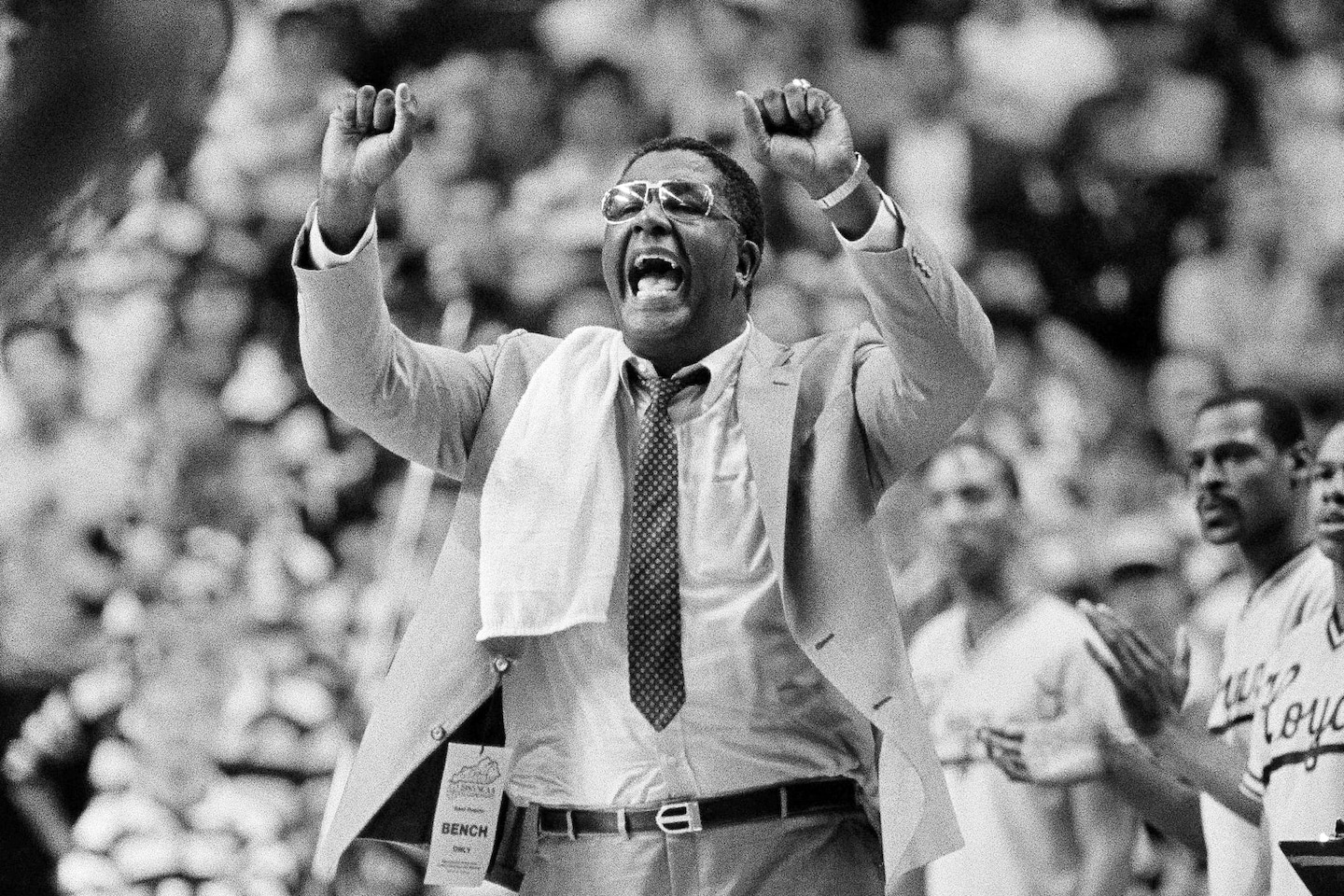

John Thompson led Black America’s basketball team

“That was Black America’s team,” says Spike Lee, the Oscar-winning filmmaker and unabashed Hoyas fan. “The ‘hood loved Georgetown. To see this big brother as the coach, to see how he protected his players as if they were his sons — to have so many in the White media be against them because of what he believed in and who he was — was to feel so much pride for them.”

“It’s why, whether you were from D.C. or New York, if you were Black, you wanted them to be victorious.”

Thompson, the patriarch of Georgetown men’s basketball, the first African American coach to win an NCAA Division I title, an outspoken advocate for racial justice and societal change, a baritone-voiced purveyor of conflict who knew two languages (“I speak English and profanity”), died Sunday. He was 78.

It’s hard to envision now but, in the 1980s, journalists didn’t lose their jobs for calling a Black coach the “Idi Amin of Big East basketball,” as a Salt Lake Tribune writer did, likening Thompson to the brutal Ugandan dictator. Students weren’t expelled for holding up signs at games alleging “Ewing Can’t Read,” as happened in 1983 during a game at Providence — until Thompson pulled his players off the court and refused to bring back All-American center Patrick Ewing and the rest of his team until the sign came down.

Today, when an NFL backup quarterback kneels before a game, Nike might sign a socially conscious athlete such as Colin Kaepernick to a multimillion-dollar endorsement deal. Entire teams boycott NBA playoff games to protest racial injustice. In 1989, though, no coach had the conviction to walk off the court before two games to protest racially biased college-entrance achievement tests.

No coach but “Big John,” who didn’t care if being woke made him broke, and who refused to be a homogenized, palatable Black man to appease ill-intentioned White America.

Thompson didn’t merely coach Georgetown; he lorded over the program and the lives of his players. And he detested the perception of the big, angry Black coach fielding a team of big, angry young Black men to do his bidding for all the slights he had received in his own life.

“So many false narratives,” Lee told me on Monday. “If you go back and look at what was written and what was said, it was just racist hate. It was all code. ‘Thugs.’ ‘Villains.’ We were all hip to where it came from: White America always had a problem with strong Black women and strong Black men. They wanted the subservient ones. All that [expletive]. John and sports weren’t immune to it.”

So many of us had him wrong. Favorite “Big John” story from over the years: Dikembe Mutombo — now a retired Hall of Fame NBA center and humanitarian — missed his first class at Georgetown as a freshman. He showed up to practice that day to find in his locker a one-way airline ticket — back to his native Congo.

“He said, ‘I’m sending you back to your father in Kinshasa,’ ” Mutombo said, referring to the country’s capital. “Big John said, ‘Go back home so you can work in [former president] Mobutu’s army.’ ”

“I could not believe it. It was chaos in my life. I thought it was the end of my education.”

Mutombo, who opened a hospital in Congo a decade ago, added, “He was preparing me for life. The real world. And I will always love him for it.”

Seventy-five of the 77 players who stayed through their senior year graduated while playing for Thompson. The three Final Four appearances and the 1984 national title were merely professional validations that helped Thompson further his real cause: using basketball to better his community — the Black community.

People who peddled perceptions of the militant Black man will hate that Big John had an affinity for country music; George Strait, Alan Jackson and Charley Pride competed for airtime with Marvin Gaye and James Brown during the 13 years he hosted an eponymous sports-talk radio show in D.C. Or the serrated edge to his sense of humor.

“You know what Black folks call Black History Month?” he asked, teasing listeners. “‘Mess with White Folks Month.’”

Down deep, Thompson loved being labeled, to be put in that box. It brought out his desire to show that being loud, successful, disagreeable and Black was not a crime but merely how the world should be.

“When they won, it was like Jackie [Robinson] or Joe Louis for us,” said Lee, who was longtime friends with Thompson, and whose Mars Blackmon character sometimes wore a Georgetown shirt. “The same type of feeling, this pride from within that went to such a different level than just basketball.”

His words, deeds and success went straight to humanity and on to history, which will remember him as a pioneer for what was ultimately right.

Read more: