The U.S. is still ‘missing’ more jobs than it did at the worst point of prior postwar recessions

Here’s the bad news: The nation’s payrolls are still down 10.7 million jobs, or about 7 percent, since their peak in February, when the recession began. That’s enormous. In fact, a higher net share of jobs is still “missing” today, relative to pre-recession times, than was the case even at the worst period of any prior postwar downturn.

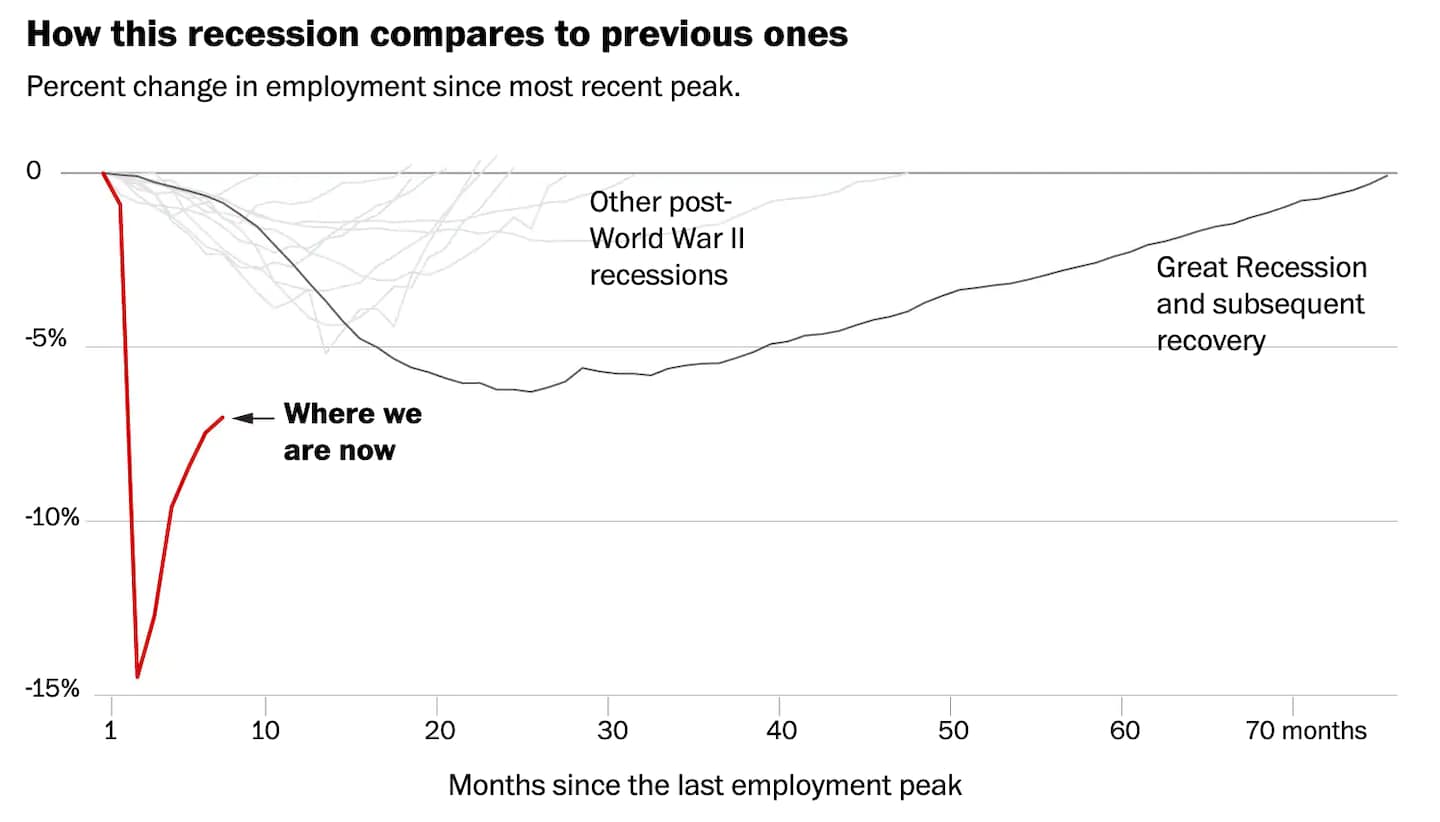

The chart below shows percentage changes in employment since the recession began, and how recent trends compare with other postwar downturns and recoveries. The black line plots the Great Recession and its aftermath. At the very worst point for the job market in that business cycle, payrolls were down about 6.3 percent. Now, however, the magnitude of those Great Recession job losses looks slightly less “great” when compared with more recent changes in employment, plotted by the red line.

Another measure of labor market health, the unemployment rate, tells a barely more favorable story.

The unemployment rate in September was 7.9 percent. This is lower than had been forecast and down from earlier this year. The unemployment rate peaked at 14.7 percent — though that official figure understated the damage due to measurement issues. Unfortunately, unemployment fell in September largely for the “wrong” reasons: because people dropped out of the labor force and stopped being formally counted as employed.

The 7.9 percent rate is also pretty close to the average peak unemployment rate of all postwar recessions.

An unemployment rate of 7.9 percent is also the highest for any president heading into a reelection contest in modern economic history. Several incumbents headed into their elections with rates above 7 percent (Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush), but none with a rate this high.

Some other observations about the jobs report:

Job growth has undoubtedly slowed in recent months. In June, the nation’s employers added an impressive 4.8 million jobs; last month, they added just 661,000. In any other recession, adding 661,000 jobs in a single month would be a tremendous feat. Not so when the nation is as deeply in the hole as we are now (again, see that first chart).

This slowdown calls into question persistent characterizations from this administration that the recovery is “V-shaped.” Yes, we initially had a sharp bounce-back. Lately, that bounce has slowed.

Any typographers out there want to take a gander at the top chart, and let me know if the shape of the red line resembles a V in any font? It looks more like some of the other shapes used to describe the recovery: a backward square root, a flaccid check mark, etc.

Some other signs suggest the recovery might slow further, including the fact that a rising share of workers who are unemployed are on permanent, rather than temporary, layoff. Several large employers, including Disney, Goldman Sachs, Allstate and airlines, recently announced more downsizing, too.

Labor-force participation is also falling, especially among prime-working-age women — driven in part by the fact that women are more likely to be primary caregivers, and in many parts of the country children are not yet back at school in person. Since February, about 926,000 men ages 25 to 54 have dropped out of the labor force. In the same period, 1.7 million women in the same age group have exited.

The chart below shows the trends expressed in terms of declines in labor-force participation rates since February.

Government payrolls also took a massive hit, thanks mainly to a decline in state and local government education employment. They shed 231,000 and 49,000 jobs, respectively. If more schools return to in-person classes, some of those jobs may be recovered. However, budget crunches caused by the pandemic recession may limit how many people are rehired.

Which brings us to the main reason for pessimism: stalled congressional talks on coronavirus relief.

As these and other measures show, Americans are still struggling and stressed. A recent Census Bureau survey found that about 1 in 10 adults was in a household where there was either sometimes or often not enough to eat in the previous seven days. The pain is most concentrated among lower-wage, service-sector and blue-collar workers; higher-wage, college-educated, white-collar workers who can continue working from home are mostly doing fine.

White Americans have also recovered about 60 percent of their lost jobs, whereas Black Americans have recovered only about a third.

It is essentially a tale of two economies. Some have suggested the best letter for describing the shape of the recovery is a K.

Perhaps because there are signs of a recovery — uneven though it may be — policymakers have not seen fit to pass more fiscal relief either to mitigate the virus or its economic consequences. Well, not all “policymakers” feel this way. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome H. Powell has been pleading for Congress to inject more stimulus, and the Democratic-controlled House has already passed multiple bills to do so. Republicans in the Senate and the White House appear to still be standing in the way. Perhaps that’s also because, as my Post colleagues reported, President Trump’s advisers are telling him that the benefits of any stimulus deal reached now would not kick in until after the election.

Without more aid coming, and with the virus still not under control, a sputtering recovery may lapse into full-on decline again.

Read more: