The legacy of slavery made my grandmother fear investing

Dear Reader,

My grandmother was fanatically frugal and a stupendous saver.

Big Mama, as she was called by all her grandchildren, showed me the power of having a well-stocked emergency fund. But for all her financial shrewdness, she did not teach me to invest in the stock market. She taught me to fear it.

When my first employer introduced a 401(k) retirement plan, I sought advice from Big Mama. But she actively discouraged me from “gambling” in the stock market.

“That’s for White folks,” Big Mama said. “They can afford to lose money.”

My grandmother trusted financial institutions to keep her rainy-day money and park her paycheck until she paid her bills, but that was it.

She didn’t even trust the U.S. Postal Service to deliver her bill payments on time. Big Mama would spend half a day every month riding around Baltimore paying her utility bill, mortgage and car loan. She made a habit of writing down the name of whoever took her cash, warning the person that if the payment wasn’t posted promptly, there would be hell to pay.

“I’ll be back,” was originally Big Mama’s line, not the Terminator’s.

My grandmother didn’t understand how the stock market worked. She wouldn’t invest in bonds, even those issued by the U.S. Treasury.

Fear drove her to save, but it also kept her from growing her wealth by investing in the stock market.

Big Mama eventually put aside about $20,000 for her retirement. But she kept it all in a simple savings account. The bank teller couldn’t even persuade her to put the money in a short-term certificate of deposit.

“No, ma’am,” Big Mama told her. “Leave my money right in the savings account.”

Those who like to pigeonhole Blacks as financial illiterates argue that the disparity results from the failure of Blacks to comprehend the importance of investing. This viewpoint ignores the history of slavery and its enduring impact on the descendants of enslaved people.

Federal Reserve data from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances found that Black families are far less likely than White families to have retirement investment accounts.

“Among middle-aged families — who have the highest rates of account ownership — 65 percent of White families have at least one retirement account, compared to 44 percent of Black families,” the Fed said.

Those who like to pigeonhole Blacks as financial illiterates argue that the disparity results from the failure of Blacks to comprehend the importance of investing. This viewpoint ignores the history of slavery and its enduring impact on the descendants of enslaved people.

And, yes, I’m back to this again.

“Well, Michelle,” you might ask, “what’s your solution?”

No, you don’t get to put this on me. You should be asking, “What can I do?”

The first thing you can do is seek to understand and empathize with how deeply discriminatory policies and practices, past and current, continue to affect Blacks.

How has your race or identity shaped your financial decision-making? Share your thoughts with us.

Let’s start with why my grandmother was so frightened of risk. Her fears went far beyond her wariness of the stock market. To see their source, I need to take you back to her past — my history.

Big Mama’s grandfather, Byrd Drumwright, was 18 when slavery was abolished. His mother, Leah, my great-great-great-grandmother, was impregnated by the White man who owned her. Our family history book used the term “impregnate” rather than “rape,” but rape is what it was because she did not have free will. Family stories passed down also told us that two of her enslaved daughters ran away after an overseer brutally beat them. They were later found dead in a river. They drowned trying to escape slavery.

Americans must stop discounting slavery as something that happened so long ago that it can’t possibly factor into the economic inequity that still plagues Black communities.

Yes, the institution of slavery ended, but not the officially sanctioned economic oppression. What came next were laws that kept Blacks from equal access to jobs that could have elevated their income enough to allow them to invest in the stock market.

Anyone who thinks this is ancient history should look at the statistics from the novel coronavirus, which has hit Blacks and Hispanics much harder than Whites because of health-care disparities and the fact that minorities are less likely to have the kinds of jobs that allow them to work from home.

“The legacies of slavery, Jim Crow, and the New Deal — as well as the limited funding and scope of anti-discrimination agencies — are some of the biggest contributors to inequality in America,” says a 2019 report by the Center for American Progress, which has been running a series on discriminatory policies. “Together, these policy decisions concentrated workers of color in chronically undervalued occupations, institutionalized racial disparities in wages and benefits, and perpetuated employment discrimination. As a result, stark and persistent racial disparities exist in jobs, wages, benefits, and almost every other measure of economic well-being.”

And if you’re not earning a fair wage, why would you risk money on Wall Street, where every adviser will tell you, “Past performance is no guarantee of future results?”

What about the history of discrimination in bank lending and hiring practices would make Blacks want to trust financial institutions? Wells Fargo’s chief executive recently had to apologize after blaming the lack of Black employees at the bank on a “very limited pool” of Black talent.

Investment bankers allowed plantation owners to use enslaved Blacks as collateral for loans.

Yes, the institution of slavery ended, but not the officially sanctioned economic oppression. What came next were laws that kept Blacks from equal access to jobs that could have elevated their income enough to allow them to invest in the stock market.

Big Mama’s grandfather was still alive in the summer of 1919 when Whites began attacking prosperous Black towns and neighborhoods across the country, including Washington, D.C., Chicago, Tulsa and East St. Louis, Ill. The spree of brutality, destruction and murder of Blacks was called “Red Summer.” Fifty-six years after the Emancipation Proclamation, Blacks got a terrifying reminder of how quickly their property, livelihood and lives could be taken away.

So, yes, it’s going to take more than a financial workshop to overcome the anxiety my grandmother lived with all her life and passed on to me.

There was only one investment that Big Mama trusted: her home.

The key to my grandmother’s retirement plan was paying off her house before she retired. This was the topic of many of her money lessons. Yet, she never viewed her home as a piggy bank. Big Mama built up equity in her home by making extra principal payments whenever she could, but she never borrowed against it.

It would have never crossed Big Mama’s mind to use her home’s equity to help me purchase my first house, which I did within two years after graduating from college with the help of a first-time home buyer’s program. Instead, Big Mama saw paying off her three-bedroom rowhouse in Baltimore as a way to stabilize her housing costs. And that for her was retirement security.

As a descendant of enslaved people who were denied the right to own anything of real value, Big Mama needed to see and touch her wealth.

Because I wanted to take advantage of the matching contributions offered in my first 401(k), I went against Big Mama’s advice and began investing for retirement. But I could only stomach contributing to bonds funds.

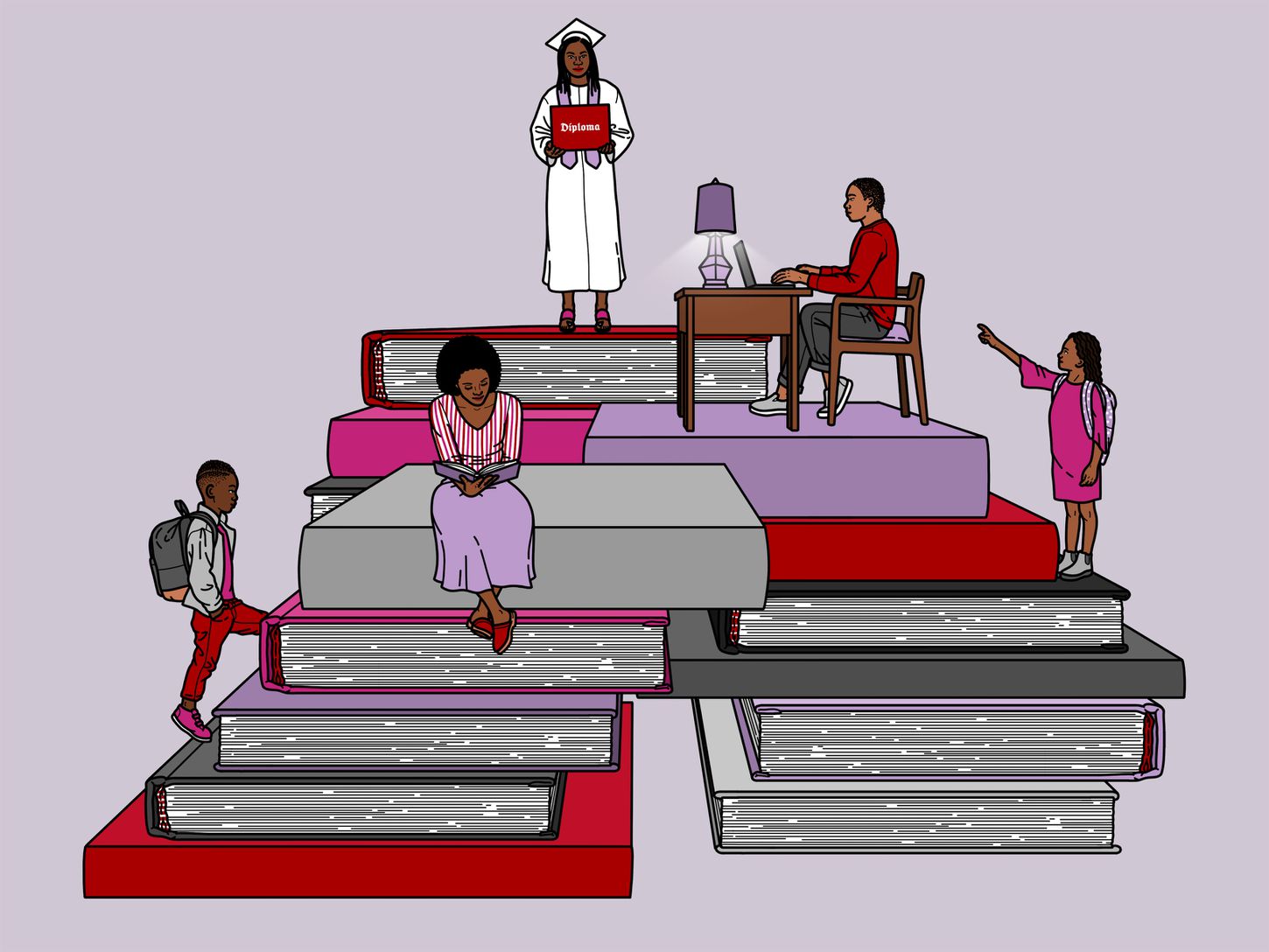

It wasn’t until my husband and I hired a Black financial adviser that I diversified into equities in my 401(k), eventually also setting up a separate non-retirement investment account that has produced solid returns. Our three children have benefited from our investment in 529 college-savings plans. They will all graduate from college with no debt.

But none of this would have been possible if not for intentional efforts to rectify decades of injustices.In my case, that included a minority scholarship that provided money for college as well as paid summer internships that led to my first newspaper job; a first-time homebuyer’s program; managers committed to increasing diversity; and a Black financial adviser who understood the legacy of slavery and helped me overcome my fears about investing in stocks.

And now, I’m teaching my children to invest.

Sincerely, Michelle

Read more from the “Sincerely, Michelle” series: