A dodgy deal helped make him a billionaire. It worked, until now.

Throughout this munificence, though, Smith had a secret: He’d played a role in what federal prosecutors allege was the biggest tax evasion scheme in U.S. history, an effort by his longtime associate, Texas billionaire Robert Brockman, to hide $2 billion from tax authorities in an offshore scheme featuring a computer program called Evidence Eliminator and code names such as “Redfish” and “Snapper.”

Smith, whose code name was “Steelhead,” according to prosecutors, has admitted to hiding profits in offshore accounts and filing false tax returns for ten years. He is cooperating with investigators and faces no charges. But his complicity in the alleged tax crimes has stunned the many who had seen a role model in the charismatic 57-year-old entrepreneur, often ranked as the wealthiest Black person in the United States.

These two sides of Smith — the impressive generosity on one and the admitted tax evasion on the other — may be hard to reconcile. But they are inextricable, according to documents reviewed by The Washington Post, including charity filings with tax authorities and Department of Justice court filings.

Both aspects stem from a deal Smith and Brockman made 20 years ago, one that joined the unlikely pair in a venture with vast ambitions. Smith, the determined son of Denver schoolteachers, was then an aspiring financier; Brockman was older and far wealthier, a man who had already made a fortune with a company that sold software for the automotive industry.

Brockman’s offer set Smith up with his own private equity firm, Vista Equity Partners, and more than $1 billion in capital to invest, according to Smith’s statement to prosecutors. That arrangement eventually allowed Smith to become a billionaire himself.

But the partnership also entailed an offshore trust to “willfully conceal” $200 million of Smith’s earnings from tax authorities, according to Smith’s agreement with prosecutors. While that account in recent years has become the source of much of his charity, it also ran afoul of rules requiring the disclosure of offshore accounts for tax purposes, according to the court documents.

It was a Faustian bargain, in other words, but at the time Smith saw mainly its benefits. It would be more than a decade before its downside would be revealed.

The statement that Smith and his attorneys signed put it this way: Brockman “presented this unconventional business proposal as a ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ offer, dictating the unique terms and unorthodox structure to the arrangement. Despite any misgivings, Smith accepted [Brockman’s] offer, viewing it as a unique business opportunity he eagerly wanted to pursue.”

Attorneys for Brockman, who pleaded not guilty, did not respond to a request for comment for this story. Smith’s statement does not explicitly name Brockman, but uses the term “Individual A” and incorporates enough work history and biographical detail to identify that person as Brockman. Brockman, who has been released, is scheduled for a bail hearing this week.

Attorneys for Smith declined to comment as well, but in a recent letter to investors, Smith wrote that the “decision made twenty years ago has regrettably led to this turmoil … I should never have put myself in this situation.”

“You can only judge people on how you know them,” said Clive Gillinson, executive and artistic director of Carnegie Hall in New York City, to which Smith has contributed more than $30 million. “I trust his integrity.”

A spokeswoman for Mnuchin, Monica Crowley, said the treasury secretary was unaware of the tax investigation at the time he and Smith were talking about how to design relief legislation.

Origins of a private equity billionaire

By the time Brockman and Smith met in 1997, Smith seemed destined for success. Ambitious and determined, he has described himself as the product of what he has called “a family of achievers.”

Growing up in Denver at the beginning of desegregation, Smith took a bus across town from his predominantly Black neighborhood to attend mostly White schools. Both his parents had earned doctorates in education, he has said.

“My older brothers were with me, walked down to the end of the block, get on the bus, and drive for 35, 40 minutes — seemed like forever,” he said in a 2019 interview with Reid Hoffman, co-founder of LinkedIn. “To now walk into a community of students that looked nothing like the kids I was accustomed to. But like all things, the thing we figured out was guess what? We had more alike than we had different. … That was a big part of my upbringing.”

He earned a chemical engineering degree at Cornell and then, after corporate jobs at Kraft and Goodyear, got an MBA from Columbia. His next job was an investment banker at Goldman Sachs, a position that alone would have been a mark of elite success.

But Smith had his eye out for more, and while working for Goldman Sachs in 1997, he met Brockman and came to admire the operation of the older man’s software company, then known as Universal Computer Systems.

The meeting was critical for multiple reasons. It introduced Smith to his first major investor, which can be a crucial hurdle for anyone with his aspirations. It also introduced Smith to Brockman’s business model, one that Smith would use as a template at the software companies his private equity funds would buy and sell.

As Smith recalled in a 2018 interview with David Rubinstein, co-founder of the private equity firm the Carlyle Group: “I then run into this small company in Houston, Texas, that is the most efficient software company I’ve ever seen. They had some very basic things that they just did extremely well. I said ‘Wow, if you took those basic things and actually applied them ultimately to other enterprise software companies … it would create tremendous value in those companies.’”

It was sometime in the late 1990s, according to the statement signed by Smith, that Brockman approached him with the idea of creating a private equity fund. Smith set up what would become Vista Equity Partners, and Brockman invested $1 billion into it.

It was a tremendous investment, but Brockman’s money came with some strings, according to Smith’s statement. One requirement was that Smith keep half of his earnings from their private equity fund in an offshore account. That was done because in the event of any disputes, Brockman wanted to avoid litigation in U.S. courts.

In his statement, Smith also said that Brockman instructed him not to discuss the offshore accounts with other attorneys. Brockman’s attorney, meanwhile, told Smith that the paperwork he and Smith prepared would make it appear as if the income and assets of the trust were not owned or taxable to Smith, according to Smith’s statement.

“They gave me one of those offers that looked quite interesting,” Smith recalled in the Rubinstein interview. “I remember my lawyer said, ‘This is a bad deal, Robert, but you should take it.’”

For anyone, the offer likely would have been tempting, but even more so for an aspiring Black financier or others from underrepresented groups, people in the industry said.

“To get people to give you hundreds of millions of dollars in order to execute your strategy … it’s hard for anyone, but particularly hard for a Black person,” said Charles Hudson, managing partner at Precursor Ventures, an early-stage venture capital firm.

“I’ve never been offered that amount of money — with strings or without,” said Hudson, who is Black. “If someone offers you a big check, it’s going to be attractive.”

From that starting point, Vista Equity Partners blossomed, buying and selling investments in software firms. Smith applied the business tactics he’d taken from Universal Computer Systems to improve the companies the fund bought, increasing their value. While Smith led the private equity firm, Brockman continued to advise on investments, according to the indictment. At times, executives from the firms they invested in were brought to visit Universal Computer Systems.

“Robert [Smith] was a visionary and an energizing presence,” said an executive from one of the companies in the Vista Equity portfolio, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to maintain contacts in the industry. “It wasn’t just luck. Brockman gave him the original capital and the idea. It was him and his team after that.”

Discovery, then a flurry of charity

Eventually, however, the risks of his old deal with Brockman became manifest: Sometime between November 2013 and January 2014, Smith received a clue that U.S. tax officials were scrutinizing his accounts.

During that period, officials at a Swiss bank advised Smith the bank was going to participate in a U.S. Department of Justice program for the disclosure of Americans’ overseas accounts, according to Smith’s statement. The bank requested that Smith waive the secrecy of his account and recommended he apply to a voluntary IRS program to disclose foreign money.

Smith applied for the IRS program in March 2014 but was quickly rejected. This is typically a sign the agency already is scrutinizing the applicant’s tax filings, former federal prosecutors said.

When a person’s application to the program is rejected in this manner, “the IRS is basically telling you … that the IRS knows something about you or is looking at your returns already,” said George Abney, a former prosecutor in the Justice Department’s tax division who is now in private practice. “It could be something small, or it could be something large, as it appears to have been in this case.”

The standard legal advice, in such situations, Abney said, “is to go ahead and fix everything. That way if the IRS does come knocking, you can tell them we’ve already corrected the problem and that will put you in a better light.”

It is about this time that Smith became a major philanthropist, frequently making headlines with his generosity.

He’d previously used $13 million in untaxed funds to make improvements to a residence in Colorado and fund “charitable activities at the property,” the Justice Department said in a news release announcing its deal with Smith. That property appears to be Lincoln Hills, established in the 1920s to offer Black people a mountain getaway in the era of segregation. Smith converted it into a vacation home for his family and used it to host former foster children and trafficking victims. He also co-founded a nonprofit, Lincoln Hills Cares, that provides outdoor opportunities for Colorado’s underprivileged youth.

His big foray into philanthropy started in 2014, when he established the Fund II Foundation, and filled its coffers with over $182 million in assets from the offshore accounts where he had hidden his income, according to the Department of Justice and the foundation’s tax filings.

Why Smith initiated so much charity at this point is unclear. But over the same period, Smith’s personal life and his business were undergoing major upheavals.

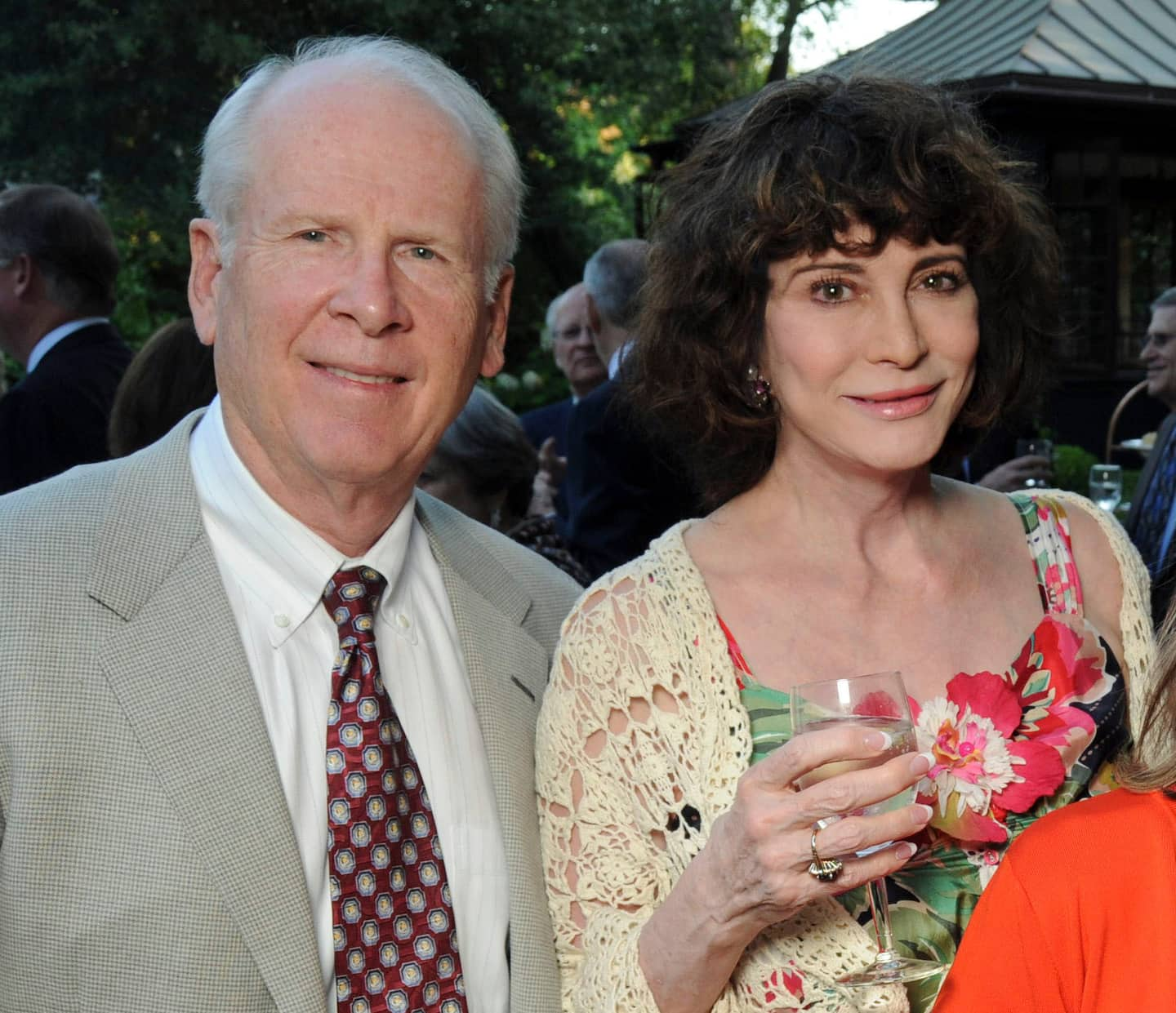

Smith divorced his first wife in 2014 and in July 2015, he married Hope Dworaczyk, the 2010 Playboy Playmate of the Year. John Legend and Seal were among the performers at a luxurious celebration in Italy.

The same month, Smith and his partners sold a minority stake in Vista Equity Partners to another private equity firm, a move that likely would have enriched him, better enabling him to become a donor.

The charity moves also might have been strategic, too, some tax experts said. If the money in the offshore entities was going to good causes, the tax evasion might strike prosecutors and juries as less wrongful.

The large donation to his foundation came from a Belize-based trust called Excelsior, which Smith controlled, and consisted of shares in a second offshore entity, a Nevis-based shell company called Flash, according to the foundation’s tax filings and statements by the Justice Department. These were the same entities Smith had established in 2000 in his agreement with Brockman, according to Smith’s statement. As part of his agreement with the federal government, Smith admits that he used those entities to hide over $200 million in income.

The foundation states on its website that the money in those entities was always meant to go toward charity. The foundation was formed pursuant to an agreement between Smith’s private equity firm, Vista Equity Partners, and the Bermuda-based company that Brockman had created to invest in the Vista fund. The foundation says the parties agreed that when the fund wound down, any leftover assets would be given to charity.

But according to the statement Smith signed with prosecutors, Smith “knowingly and intentionally falsely claimed that this charitable contribution was required as part of an agreement” with Brockman.

Regardless of these charitable donations from the offshore entities, however, some attorneys said, Smith is fortunate to have avoided criminal prosecution, especially given the scale of the tax evasion.

“The idea of a billionaire tax cheat getting immunity to cooperate against another billionaire tax cheat strikes a lot of people as out of step,” said Justin Weddle, a former federal prosecutor who handled several large tax cases and is now in private practice. “For Smith to get a non-prosecution agreement for cooperation is very unusual.”

Under his deal with federal prosecutors, Smith abandons claims for a $182 million tax refund, which consisted partly of claims for charitable deductions that he made in 2018 and 2019, the Justice Department said.

Weddle noted, too, that the tax evasion scheme strikes him as particularly ill-advised strategy for both Brockman and Smith, because while it might have saved them tens of millions of dollars, those amounts are small compared to their huge fortunes.

“It strikes me as dumb,” Weddle said. Smith “was risking criminal prosecution for a tiny portion of his portfolio.”

To review his tax situation, Smith had earlier hired tax attorneys including Charles Rettig, whom Trump appointed as IRS commissioner in 2018, according to two sources familiar with the hiring but who were not permitted to speak publicly. It is unknown what advice Rettig or the other tax experts gave Smith.

“The Commissioner did not have any role in the DoJ investigation into Robert Smith,” the IRS said in statement. “Without acknowledging whether the Commissioner represented any particular client in any particular matter while he was in private practice, the Commissioner recused himself from all such matters upon taking office.”

Tax experts said wealthy people such as Smith can reap significant financial benefits from their charitable gifts and can enhance their public reputations.

“It’s certainly a very troubling case in terms of shining a light on the extent to which wealthy Americans are avoiding taxes through offshore vehicles,” said Ray Madoff, a professor at Boston College and an expert on philanthropy and taxation. “On the charitable side, it raises questions about people’s ability to offset significant taxable income with charitable donations.”

Whatever the reasons for his charitable giving, there have been many beneficiaries, most of whom continue to praise his efforts.

Shortly after its funding, the foundation went on a philanthropic spree, making huge donations to Cornell University, the United Negro College Fund, the National Park Foundation, Susan G. Komen, and other causes. A building at Cornell University, Smith’s alma mater, was named for him.

Paula Schneider, president and chief executive of Susan G. Komen, a breast-cancer foundation, said that in 2016, Smith awarded the foundation more than $10 million worth of shares of his Fund II Foundation. That money, Schneider said, was used to start a 10-city initiative to examine why Black women have disproportionately higher rates of breast cancer.

“Robert has been an amazing benefactor for us. I can only speak to that. He has been very generous,” Schneider said.

Gillinson, of Carnegie Hall, said he was introduced to Smith seven years ago, before he had become well known. The two spoke of their love for music and the arts and Carnegie Hall’s mission to start an education program to introduce music to children, Gillinson said.

In 2015, Smith gave $15 million to enable Carnegie Hall to create a national program to introduce 5 million children to music over a 10-year period through school systems. Two years later, Smith gave an additional $10 million for an arts and education program expansion. In the following years, Smith gave $5 million to expand the music education program and $2 million to fund Carnegie Hall’s National Youth Orchestra, which travels the world performing music as ambassadors for the country.

Gillinson then asked Smith to join the Carnegie Hall board, and in 2016 he was elected its chairman.

“Everyone has absolute belief in Robert,” Gillinson said. “He’s somebody who has integrity and a real sense of commitment to the things that matter in the society we live in.”

Smith received the most attention, however, for his surprise announcement at the 2019 Morehouse commencement ceremony, in which he pledged to wipe out the student debt held by that year’s graduating class. The sum, which would come to include the educational loans taken out by the students’ parents, ultimately would reach $34 million.

Morehouse President David A. Thomas described Smith’s $34 million gift, a year after Smith had already given the school $1.5 million, as “catalytic,” inspiring other philanthropists to give to other historically Black colleges and universities around the country. This year, annual gifts to HBCUs will exceed those of any other in their 170-year history.

“All of those gifts were anchored in what Robert did,” Thomas said.

Yet the news of Smith’s involvement with Brockman has left many wrestling to understand what happened.

Smith is “an African American billionaire who up until this moment, for the most part, appeared to have basically fulfilled the American Dream,” Thomas said. He “had humble beginnings, education was his elevator up through Cornell University and Columbia, he played by the rules, became an innovator when he created Vista and focused on tech.”

Thomas believes Smith agreed to Brockman’s offer because, while it gave Brockman more control over his offshore assets than Smith might have wanted, it made his financial dreams a reality.

“This was 20 years ago and a 36-year-old brown man running around Wall Street trying to get people to invest in a very big idea. Not a lot of takers. Then he gets a billion-dollar investment. That’s how he built an empire that made him a billion dollars.”