Job growth will slow during a Biden presidency: The easy gains are almost gone

Job growth has decelerated every month since June, and there are some signs from the hard-hit travel and restaurant industries that the fast-spreading novel coronavirus could put economic growth into reverse.

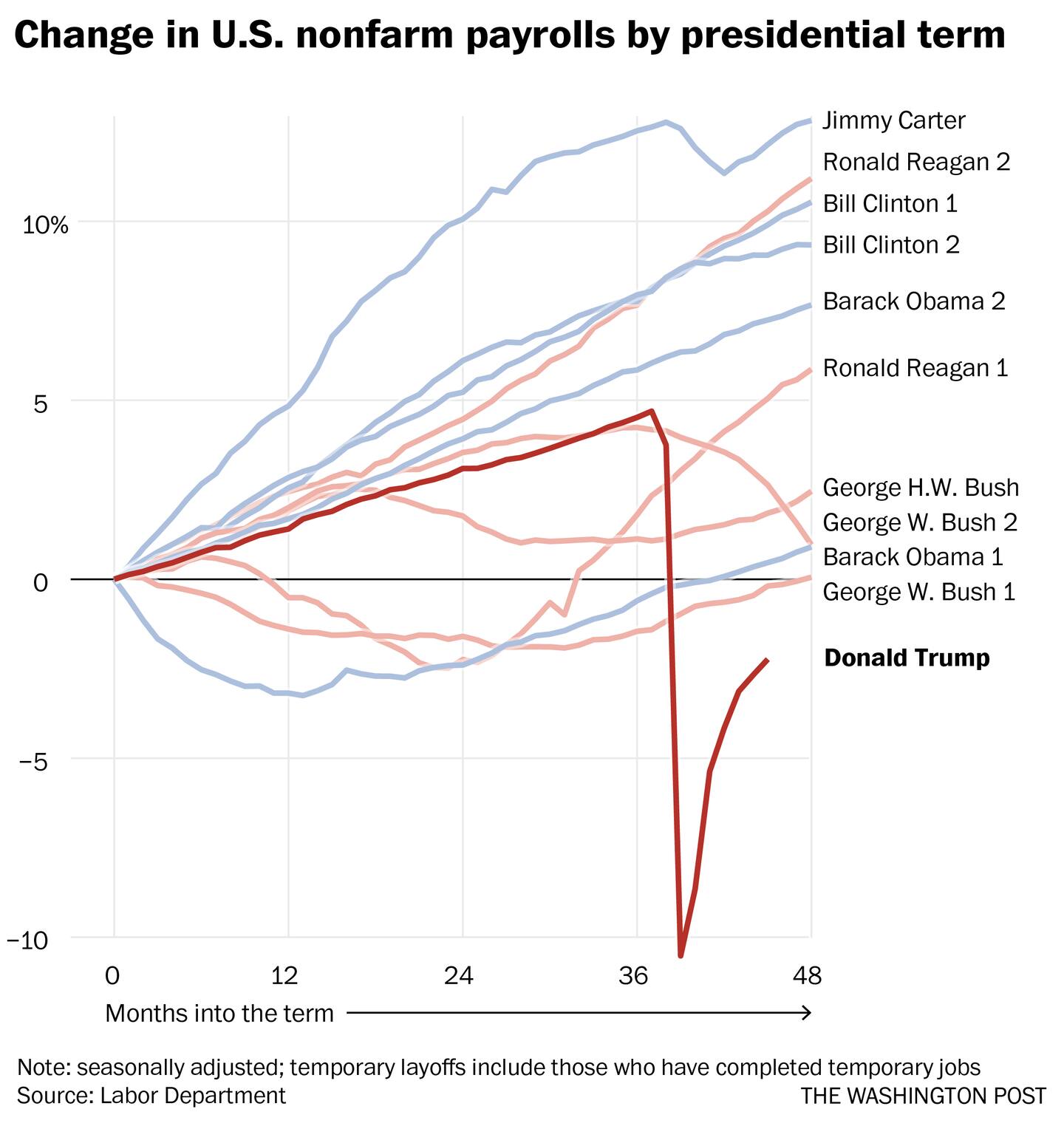

President Trump’s single term in office is poised to end with apocalyptic job losses followed by a string of impressive monthly job gains. That has less to do with policy and more to do with how the coronavirus crisis hit swifter and deeper than anything before it, giving plenty of room for a rapid early recovery, as businesses reopened and $4 trillion in federal aid washed through the economy.

In April, as the U.S. shutdown deepened, 18.1 million laid-off workers said they expected to be called back to their employers, Labor Department data shows. As of October, there were only about 3.2 million of them left — the rest were either rehired or, in some cases, laid off permanently. That flood of workers returning from temporary layoffs translated into rapid employment gains. Over the same period that temporary layoffs ended for 14.9 million workers, the economy gained 16.4 million jobs.

The vast majority of workers leaving temporary layoffs appear to be returning to their previous jobs, according to Eliza Forsythe, a labor economist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and a recession specialist who has dug into federal data on the temporarily unemployed in recent work.

Not all of those who left the ranks of the temporarily unemployed got their jobs back, of course. Some of them were laid off for good, as were some of their unemployed peers. Even as the number of temporarily laid-off workers plunged, the number of those permanently laid off doubled. By October, most layoffs were permanent. If unemployed workers were going to get their jobs back, they probably already had.

And the ranks of those permanently laid off are likely to rise. Well over a million workers are still being laid off or fired each month. And to be counted in the above chart, which includes only the unemployed, people need to have actively sought work in the past month. That means the chart excludes about 3.7 million workers who have quit working or looking for work entirely since the pandemic hit — and many of those workers will be added to the total number of unemployed once they’re looking for work again.

“Once the pandemic is over, once schools are opened, once it’s safe to go back to work, they’re likely to go back to the labor force,” Forysthe said.

But signs are growing that the labor market could get worse before it gets better. Job losses continue to spread to high-skill sectors once considered safe from the pandemic’s fallout.

In late October, the announcements came strong and fast, and not just from oil companies like ExxonMobil and entertainment companies like Disney, but across the board. For example, Austin tech company National Instruments announced at the end of October that it would lay off about 650 of its workers worldwide, the Austin American-Statesman reported. And according to the Philadelphia Inquirer, schools in Pennsylvania’s state university system moved to lay off more than 100 full-time faculty, 80 of whom either hold tenure or are on the tenure track.

Economists say such job losses may take longer to recover from, as it can be difficult for specialized workers to find positions that match their skills and expectations.

Workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher initially avoided the worst of the crisis; many of them could work from home. By August, they had recovered their job losses entirely. But as layoffs spread from service jobs to the white-collar and back-office jobs they support, college-educated workers are losing ground. In September and October, America’s extensive college-educated workforce actually shrank.

About 1 in 4 of their less-educated counterparts lost their jobs earlier in this recession. But those groups recovered rapidly and have shown healthy job gains in recent months — they’re more than two-thirds of the way back from the depths of the recession.

In another sign that the downturn has spread to skilled jobs not directly affected by the initial coronavirus shutdowns, we saw continued losses in education and other jobs that rely heavily on public-sector funds.

“The recession has led to a dramatic fall in tax revenue for state and local governments, which temporarily upends their budgets,” Forsythe said. “Once the economy recovers, they’ll be back on track, but without federal support they have to make cuts.”

Lack of adequate federal support forced state and local governments to slash payrolls during the Great Recession, Forsythe said. It’s one of the reasons the economy took so long to dig out of the Great Recession, and current weakness in the public sector is a warning sign it may be happening all over again. A potential public-sector bailout has long been a sticking point in negotiations over a second round of stimulus.

In almost every direction, Biden will face stronger head winds than his predecessor. The clearest potential job gains have already been realized, the coronavirus is spreading through the U.S. population seemingly unchecked and prospects for broad government stimulus are uncertain.

We won’t have comprehensive data on fourth-quarter economic output until next year, but early signs of trouble have already appeared in real-time measures of activity for the hard-hit travel and restaurant industries.

Data from the Transportation Security Administration shows that the number of passengers lining up at TSA checkpoints has fallen in recent days. After a promising start to the much-reduced fall travel season, air travel is back to a third of what it was at the same time last year.

The reservation app OpenTable shows a similar pattern. Restaurant activity had been picking back up but slipped in October as the pandemic gained steam and diners stayed home. Now it stands at about half its usual level.

One way to think about pandemic-era unemployment benefits is that the government is paying workers to stay home to limit the spread of infection. If pandemic-related benefit expansions aren’t renewed before they start to expire in December, Americans could be forced to return to workplaces before it’s safe to do so. That could create a vicious cycle of infection, Glassdoor senior economist Daniel Zhao said.

Workers who lose their benefits may be pushed to return to the workforce just as the pandemic goes into overdrive. That could accelerate both the spread of the virus and the plunge in economic activity.

“It’s certainly possible that we could see job losses in the November report, or even in one of the other winter reports, depending on how the pandemic evolves,” Zhao said.

To be sure, despite the likely short-term slowdown, Biden could post one of the best longer-term job-creation records of any president in recent memory. His secret weapon isn’t a particular skill or policy, it’s just that the economy is operating well below its capacity. Unlike President Barack Obama, who took office while the economy was still losing jobs, Biden will take office when the economy seems to be stumbling toward recovery but remains about 10 million jobs in the hole.

If Biden did nothing more than recover the remaining ground lost, he would do far better than Trump during his term, when Republicans gained about 6.8 million jobs before plunging deep into negative territory amid a bungled response to a completely unforeseen global pandemic.

It won’t happen at anything like the average pace of a million-plus jobs a month we’ve seen so far during the early months of the recovery, but if all that slack in the economy permits faster-than-usual job growth, it’s likely Biden will top both President Bill Clinton’s terms (11.6 million and 11.3 million) and Obama’s second term (10.4 million), which have set the gold standard for recent decades.

Heather Long contributed to this report.