Sports has a Gen Z problem. The pandemic may accelerate it.

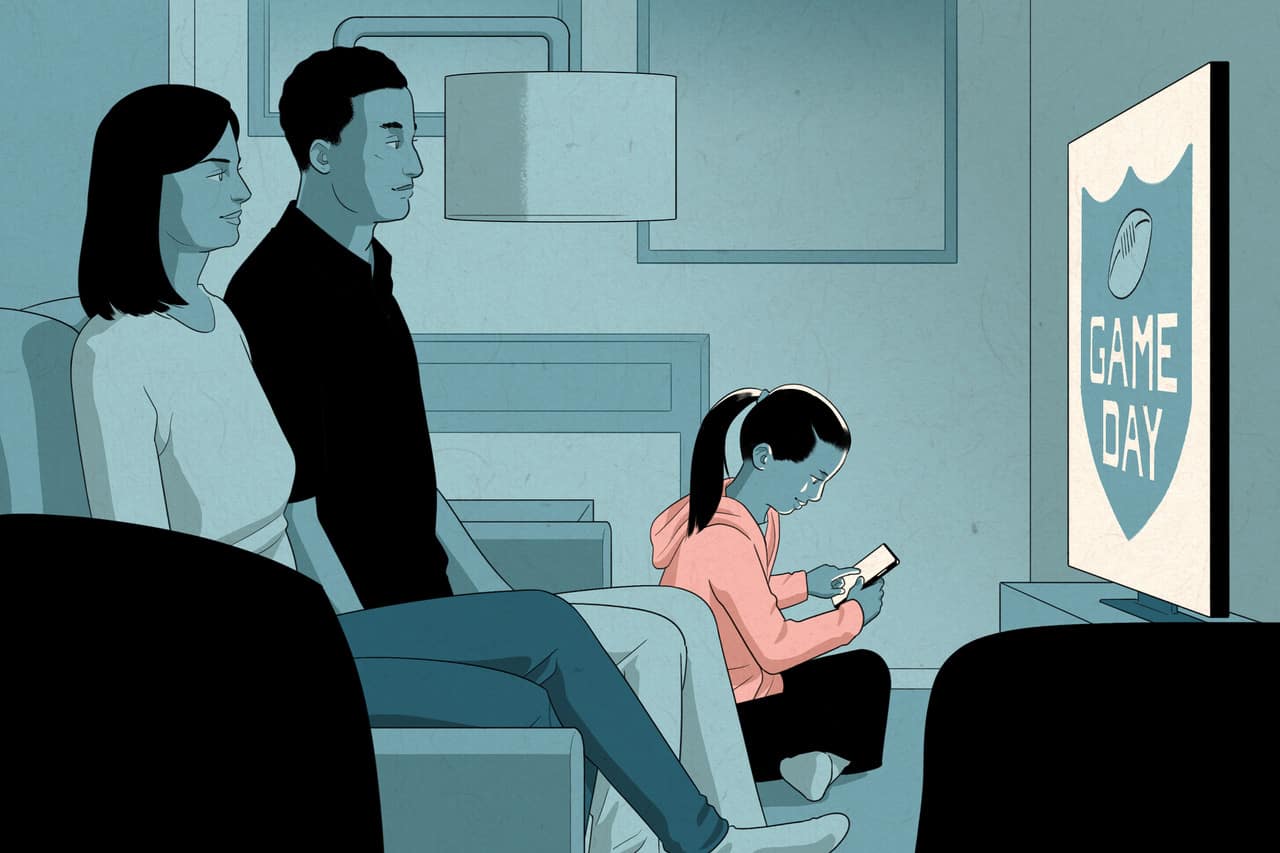

The bulky and bankable U.S. sports industry, built on towers of cash and lucrative television contracts, is confronting a Generation Z problem. The nation’s youngest cohort is fundamentally different from the generations that preceded it. Having grown up with smartphones in their pockets, its members eschew traditional television-viewing and subscribe to digital habits that make grooming a new generation of sports fans a challenge.

That challenge is being met with a sense of urgency in some corners of the sports world and a sense of alarm in others, according to interviews with team and league officials, social scientists, research analysts and marketing specialists who focus on Generation Z. Failing to hook young people might not devastate today’s bottom line, but it threatens to muddle the future of every league, every team and every sport.

“If you lose a generation, it destroys value and the connective tissue,” said Ted Leonsis, principal owner of Washington-based teams that compete in the NBA, WNBA and NHL. “It’s what some of the big sports leagues are nervous about. Could we lose a generation because we didn’t give them access and the products and services they want?”

While many have embraced digital platforms, leagues and teams were slow to tailor their offerings to the youngest generation, even as research made clear that Gen Z members — loosely defined as those born after 1996 — interact with the world much differently than millennials, Gen Xers and baby boomers. And these habits have taken a toll on the way they engage in sports, research shows. According to ESPN’s internal data, some 96 percent of 12- to 17-year-olds still identify as sports fans, a consistent figure over the past decade. But the share of fans who call themselves “avid” has been dropping, from 42 percent a decade ago to 34 percent last year.

Rich Luker is a social psychologist and founder of Luker on Trends, a sports polling outfit that has been measuring fandom and consulting with pro leagues for more than a quarter-century. He has been watching fandom drop among young people for the past decade and sounding alarms.

“I’ve been screaming for 15 years now,” he said. “I would get push-back. Owners, executives, senior-level people say, ‘They will come back at 35.’ Why would they come back at 35 when they were never there in the first place? That’s like saying all of a sudden they’ll all start knitting at 35 or watching cricket at 35. Why would they do that?”

Tim Ellis, the NFL’s chief marketing officer, says the league’s own data bears that out. “There’s no strategy for bringing in a 35-year-old fan for the first time. You have to make them a fan by the time they’re 18, or you’ll lose them forever,” he said.

That’s why the NFL has been so worried in recent years. When Ellis joined the league two years ago from Activision Blizzard, the popular video game maker, the league had seen its young audience trend downward for six straight years. He stressed to team owners that finding a solution was urgent.

“Gaining and retaining young people is key to future-proofing the NFL,” he said in a recent interview. “So when we look at that generation, I personally look at it as the lifeblood and health of the brand and our business.”

The issue has only been exacerbated by the pandemic, as youth sports suffer and young people spend more time than ever online.

Sports executives “haven’t paid enough attention yet to this generation, and they have to,” said Mark Beal, an assistant professor at the Rutgers University School of Communication and Information who has written two books on Gen Z. “They need to prioritize them because these are the sports fans of the future that over the next 10 to 15 years can make or break a sports team, league or manufacturer. This is your most important consumer, and they’ll determine your future success.”

Future fans sidelined

Last month, Beal gave an online presentation to executives from Major League Baseball and its 30 teams. To explain how this younger audience is growing up innately different, he borrowed a quote from Jacqueline Parkes, the chief marketing officer for MTV: “This is a generation that grew up swiping before they wiped.”

Over the course of 60 PowerPoint slides, Beal painted a stark portrait of how technology shapes the way Gen Zers navigate the world. They’re globally conscious and care about diversity, equality and inclusion. They get their news from Instagram and YouTube, not a newspaper or cable news network. And they want unique, authentic experiences — even better if it’s something they can then share on their social networks.

They do enjoy sports, Beal says, though other, digitally friendly pastimes compete for their attention. He surveys Gen Zers a handful of times each year and finds that sports consistently rank behind entertainment (music, movies and TV) and pop culture (celebrity news and trends).

This was not all new information to the Zoom-assembled baseball executives. Officials from MLB, the NBA, the NFL and the NHL all say they’ve been diligently studying Generation Z. They have ramped up their efforts to connect, they say, and are pleased with the early returns.

But many acknowledge this is a tenuous time. Leagues’ research shows a strong correlation between young people playing a sport and developing fan loyalty. But youth sports participation has steadily slipped in recent years. There were promising signs more recently — and then the pandemic struck. One emerging fear, though it’s probably too early to quantify, is that the hit to youth sports will do permanent damage, with young people gravitating in other directions or getting further engrossed in their digital worlds.

There are other defining Gen Z characteristics that encourage sports executives. Members are highly engaged, devour content and crave connection.

“The draw for sports historically has been this idea of connecting with others and creating interactions and connection points, whether at the ballpark or the water cooler at the office,” said Chris Marinak, MLB’s chief operations and strategy officer. “… We see the younger generation has that same desire, probably even more so in terms of connecting with friends.”

A new game plan

These complicated consumption habits have forced teams and leagues to throw out their time-honored blueprints and find new ways to welcome Gen Z into the tent. Young fans might not sit through nightly 2½-hour (or longer) televised games, but they’re receptive to shorter videos on platforms such as YouTube, TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat.

“The challenge isn’t about finding Gen Z,” said Kate Jhaveri, the NBA’s chief marketing officer. “It’s about attracting and keeping their attention.”

The NBA has been ahead of the curve there. Forty percent of the league’s core fan base is under 35, and the league is finding success engaging young fans online, where it has 148 million followers across the major social media platforms — more than the other U.S. leagues combined. It has seen 43 percent growth in social media views in the past three years.

While last month’s NBA Finals attracted disastrous TV viewership, the league insists that different metrics are needed to measure modern fandom. Many fans, especially the youngest set, were still consuming content online, the league says. For the year, the NBA’s videos have been viewed 13.2 billion times on social media, again more than those of the other major leagues combined.

Those views might plant seeds for future loyalty, but they don’t offer the same revenue flow that comes from traditional means. An analysis by the sports marketing agency Two Circles suggests that value of short-form video rates will increase more than 100 percent in the next four years, compared with 18.7 percent growth for live rights. But the overall value of live rights will still be at $49.1 billion in 2024, dwarfing the $3.2 billion valuation of short-form videos.

For now, executives say, hooking new fans is the key.

“The traditional sense of being a fan — either buying tickets and going to the game or watching every game on television — those are still very important,” said Heidi Browning, the NHL’s chief marketing officer. “However, you can also be a fan and consume everything digitally — highlights, stories about your favorite athletes. You can buy jerseys; you can play video games. You’re a fan, too, but your way of interacting with the sport is different than what we’ve traditionally thought of as fandom.”

Betting on tech

Leonsis is a former senior executive at America Online and has long had his hands in a wide variety of technology companies. He says appealing to a Gen Z audience amounts to an “existential issue facing the sports world” that he has worried about for decades.

“When I bought the teams in 1999, I went to the leagues and said internally, it’s going to happen to us: We’re either going to make dust or eat dust,” he said. “We have to get in front of this and innovate.”

Leonsis noticed a major shift when his son, Zach, went to college a dozen years ago and needed a television and cable subscription. Just a few years later, when his daughter, Elle, started school, she was content with a tablet that could stream video.

At Monumental Sports, which owns the NBA’s Wizards, NHL’s Capitals and WNBA’s Mystics, Leonsis is constantly tinkering, trying to anticipate where the audience is going. The organization runs its own digital sports network and has been aggressive in esports, purchasing a team in the NBA2K League and investing in Team Liquid and Epic Games, which produces the popular Fortnite title. It has also dived headfirst into sports betting, becoming the first pro sports team to host a sportsbook at its arena. As legal sports gambling expands nationwide, Leonsis is convinced that betting is a key to making games more interactive and engaging.

The major U.S. sports leagues have similarly become aggressive in both gaming and gambling. They have struck partnerships with betting operators and daily fantasy services and have become active in esports. The NBA runs its own video game league, and the NHL hosted a global esports tournament this year. All of the major leagues are also now on Twitch, the popular streaming service for gamers.

“If Gen Z doesn’t think traditional sports are cool, that doesn’t help anyone,” said Zach Leonsis, now 30 and serving as Monumental’s senior vice president of strategic initiatives. “It waterfalls down to the generations after them. So we’re not looking at Gen Z in the nutshell. It’s Gen Z and everything that comes after.”

One key for all the leagues has been aligning their interests with those of young fans — fashion and music, for example. Another big area: social issues. The NFL hosts a social media summit every offseason in which executives from the major platforms and popular influencers lead instructional sessions for top players. This year’s summit took place online and was focused on social justice.

The other leagues have also embraced “cause marketing,” tackling social issues that range from voting to mental health to social justice. “We know that what this Gen Z audience really cares about also happens to be what our players care about,” the NFL’s Ellis said.

Marketing departments across sports are now filled with employees plucked from social media companies, video game producers, streaming services and other youth-oriented brands. Browning came to the NHL four years ago from Pandora, the streaming music service. She knew young consumers had developed different habits and expectations, but she also noticed that they constantly evolve.

So the NHL launched a Gen Z focus group last season, a panel of 15 young people who met on Zoom and chatted on Slack. The league peppered them with questions, took notes, adjusted strategies. As a result, it has changed the content the league pushes out to fans. Five years ago, online videos might have been overwhelmingly one-timers and stick saves. Now, Browning says, the mantra is “humans are greater than highlights.”

“They want to see our players in their real lives, see them with their wives, know what they eat or drink or are binging on Netflix,” she said.

Other leagues have a similar approach, humanizing athletes and giving young fans new access to the games. In a partnership deal that includes Twitter, the NFL this season set up end zone cameras to capture elaborate touchdown celebrations, once a source of consternation for league officials. “That was 100 percent focused on that younger audience,” Ellis said.

MLB’s YouTube channel features a wide variety of offerings: a celebrity chef making the favorite meal of a Miami Marlins pitcher, New York Mets first baseman Pete Alonso mic’d up during games and videos explaining why managers wear uniforms and how different pitches move.

“They may not be as conducive to sitting down for three hours and watching a game from start to finish, but they’re consuming the same levels of content,” said MLB’s Marinak. “It’s just in different forms.”

The leagues all say they’ve made progress, even as sports-television viewership struggles amid the pandemic. Ellis says the NFL has recently stemmed the losses of its youth audience, and ESPN’s internal research suggests the number of young Americans who say they’re “avid” fans rose slightly in 2020 to 38 percent. But executives know that Gen Z is a puzzle that’s constantly shifting.

“You can’t ever think that you have it solved,” Ellis said. “It is just going to keep evolving.”

Ben Strauss and Emily Guskin contributed to this report.

Read more: