How film festivals can help combat Chinese censorship

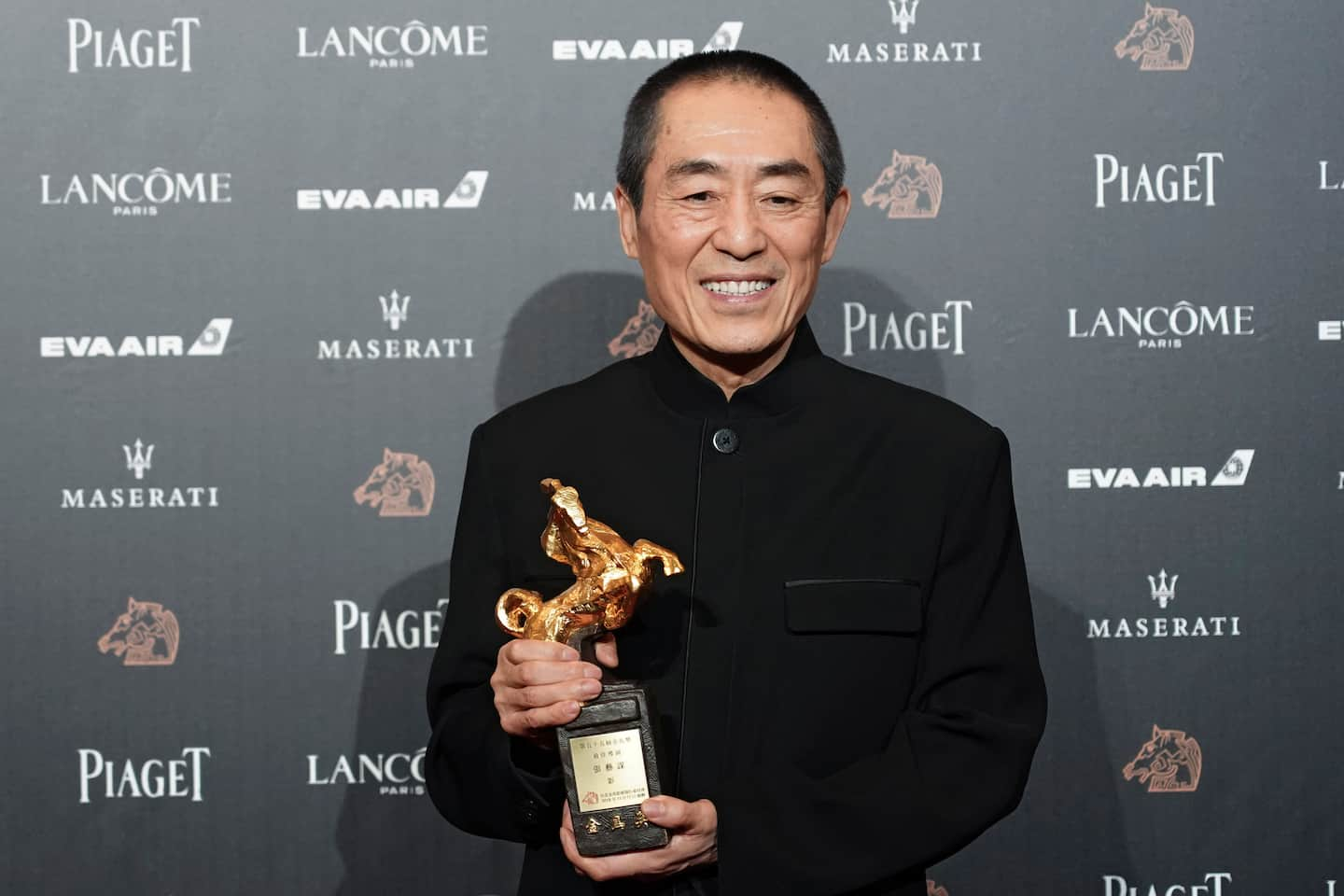

Originally slated to debut at the prestigious Berlin International Film Festival in 2019, “One Second” was pulled from the festival at the last minute for “technical reasons.” In the United States, “technical reasons” might mean something like “a print wasn’t delivered in time,” the phrase in China is a common euphemism for failing to pass muster with the state’s censorship board. Now, almost two years later and following reshoots and re-editing, Zhang’s “love letter to cinema” set during the Cultural Revolution has been cleared to play for Chinese audiences, who have received it with minimal enthusiasm.

The fate of “One Second” should serve as a catalyst for change amongst prestigious film festivals such as Berlinale, Cannes, Venice, Sundance and others. If these festivals believe in the freedom of art and the ability of artists to make art uninhibited by government pressure, they should use their prestige to help curb China’s practice of censoring filmmakers. No film that bears the stamp of official government censorship — and the so-called Dragon Seal affixed in front of movies that pass ideological muster with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is almost literally a stamp — should play at any festival that values freedom of the arts.

Granted, this might involve shutting out filmmakers from the most populous country on Earth. There would be a real cost both to artists and international audiences. But such a collective decision by festivals would be a sharp rebuke to China’s efforts to turn its movie industry into a showcase for the world. And festival access is one of the few pressure points cinema-lovers could use to help filmmakers achieve a greater level of freedom in the Middle Kingdom, according to “Feeding the Dragon: Inside the Trillion Dollar Dilemma Facing Hollywood, the NBA, and American Business” author Chris Fenton.

“Validation from the international community is big to the Chinese … particularly with an industry like the film industry that the CCP has put a concerted effort into making world class,” Fenton, who has worked with the Chinese government and American studios in an effort to increase U.S. access to the Chinese market, told me.

However, making such a move comes with risks and the only way such an effort would work is if every festival came together with one voice and said they would no longer allow censorship at their events.

“Taking a unified stand would cause the CCP to retreat. No doubt in my mind. That said, a lone-wolf approach, like say with only Berlin doing something like this solo, would probably cause a large sacrifice (lost money to the festival, retaliation against German film biz, retaliation against German filmmakers, etc.) with little positive result,” Fenton said. “However, if multiple festivals representing multiple countries took a stand — CCP would have no choice but to retreat.”

Such a hard line could have a benefit for festivals, too: Chinese releases are frequently the subject of unexpected withdrawals, forcing exhibitions to shake up their schedules. “It takes a determined — or brave — selector to program Chinese movies in prominent festival positions,” Patrick Frater noted in Variety last year after Cannes selected a pair of Chinese films for inclusion at the 2019 iteration of the French festival. “Until the film actually screens, there is an ever-present risk of an embarrassing cancellation.”

Cinephiles would undoubtedly grumble at the idea of blackballing Chinese releases, suggesting hypocrisy when, after all, American films are rated and sometimes that rating leads to films not getting proper theatrical releases. I’ve never found such grumbles particularly persuasive. As Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg put it in a roundtable interview years ago, what the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) does isn’t censorship in any real way.

“When I came down here to talk to the MPAA about ratings, it was still a relief compared with what happens in Ontario, which is where they take your picture. They take every print. And they cut it. And they hand it back to you and they say this is your new movie. They keep the pieces that they’ve taken out — and you go to jail for two years if they’re projected, if you put the pieces back. And that’s real censorship,” Cronenberg said. That right is reserved by Canadian provinces, which continue to have the power to ban films — a power local U.S. authorities were stripped of years ago.

Chinese artists face disastrous personal and professional repercussions for going against China’s censorship regime. It’s about time the world’s film festivals stopped aiding and abetting the censors who are limiting the vision of these artists.

Read more: