Alex Smith, an injured soldier and a friendship born from a shared journey

Shortly before Alex Smith walked onto the turf at Lincoln Financial Field on Sunday in Philadelphia, his phone buzzed with a text message from a friend some 1,600 miles away. It has become a recent pregame tradition of sorts, and it is usually followed by another text or phone call after the game to see how Smith felt, to celebrate his team’s run to the NFL postseason or to check on his recent calf injury.

As he prepared for the Washington Football Team’s NFC East-clinching win over the Eagles that set up Saturday’s playoff game against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, Smith responded to the well wishes with a text his friend Chris White will save forever.

“Bro, I’m the one that owes you a huge thank you!” Smith wrote. “I’m so thankful for our friendship and everything you have done to help me!”

It’s the type of response White has gotten used to receiving from the quarterback. “I know you know who Alex Smith is,” White said, “but this is truly the person that he is.”

It wasn’t that long ago when Sundays were simply an escape for White, a longtime New England Patriots fan and a married father of two. But unbeknown to him, his life changed Nov. 18, 2018, the day Smith suffered a compound right leg fracture that would become infected and threaten Smith’s life and limb, setting up two years of surgeries and rehab that led to an NFL comeback few thought possible.

White, 38, didn’t know Smith before the injury, but he now knows him better than most ever could. If anyone could truly understand his physical pain, his arduous recovery, his dark days and his moments of hope — in addition to his desire to return to a job that nearly killed him and his push for a remarkable recovery — it’s White, a former airborne infantryman who has spent years doing all of the same.

Over the past two years, the two men’s lives converged at the Center for the Intrepid (CFI), a state-of-the-art rehabilitation facility for wounded veterans in San Antonio, where White lives. Together they rehabbed from nearly identical injuries suffered in very different circumstances, and together they set out to achieve their own improbable comebacks, inspiring each other along the way and building a friendship that neither imagined.

“People don’t appreciate the journey most of the time. They don’t understand the journey,” White said. “For someone to have to live through the same journey, you get a very unique appreciation for it. And to truly become good friends after it is pretty remarkable. It doesn’t happen every day.

“Different worlds but same struggles.”

Smith’s injury threatened not only his leg but his life. (Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post)

Smith’s injury threatened not only his leg but his life. (Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post) Feeling ‘completely helpless’

The memories from July 2011 are sparse, but White still can see the vehicle speeding toward him, and he still can recall the feeling when it crashed into him.

“You ever hit your funny bone so hard that it feels like your hand is on fire?” he said. “That’s what the whole right side of my body felt like.”

White was conscious but not fully there, his body in such shock that his recall of that day is blacked out in his memory bank. He was told by those on the scene that he tried to sit up to look at his injury but was urged to lay down. His right leg was so mangled that his big toe was touching the inside of his knee.

White, who was on active duty, suffered compound fractures to his right tibia and fibula. (White declined to provide specifics of how and where the incident took place, citing possible confidentiality rules from the Department of Defense.) When his leg was put back together, he was missing approximately two inches of bone, prompting a corrective procedure in which surgeons had to re-break his leg in three places and fill the gap with cadaver bone as well as bone from both of his hips.

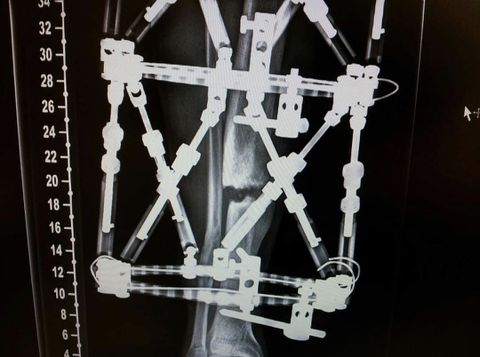

For 13 months he wore a metal external fixator, similar to the one Smith had in the aftermath of his injury, and made repeated adjustments himself — only to realize the bones failed to properly fuse. So a titanium rod and screws, which now hold his leg together, were inserted in his tibia.

“I didn’t have the crazy infection or anything like Alex did,” White said. “But our breaks were almost identical, so our recovery process was pretty much identical.”

White wore a metal external fixator for months. (Courtesy of Chris White)

White wore a metal external fixator for months. (Courtesy of Chris White) White underwent nine surgeries on his right leg, the last of which was in March 2019. After his initial month-long hospital stay in 2011, he went through nearly two years of physical therapy and treatment at the CFI, which opened in 2007 primarily to treat veterans who suffered burns and limb-salvage injuries while fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan.

White, like Smith, was considered a limb-salvage patient. But when he arrived at the CFI to begin rehab alongside triple- and quadruple-amputees, he was still using a wheelchair and uncertain whether he would ever run again.

“You go from being this very physical airborne infantry guy to being completely helpless, so you kind of carry that mentality … where you just can’t do anything for yourself,” he said. “But I rolled myself in, and I saw all these guys, and the music was really loud, and everybody’s just smiling and having a good time. And I just thought to myself: ‘It could be so much worse than where you’re really at. It’s time to get over yourself.’ Honestly, from that day on, I really just took a completely different mind-set toward everything.”

White didn’t have the option of returning to active duty after his injury. He was medically retired in 2013 because he could no longer run. Like Smith, he had lost dorsiflexion, or the ability to fully lift up his right foot, because of trauma to the nerves in his leg. Returning to his duties appeared to be unfeasible.

But that changed in early 2019, shortly after he met Smith.

White, here with physical therapist Maj. Patrick G. Manrique, was medically retired as an airborne infantryman but is trying to return. (Matthew Busch for The Washington Post)

White, here with physical therapist Maj. Patrick G. Manrique, was medically retired as an airborne infantryman but is trying to return. (Matthew Busch for The Washington Post) Recovering side by side

The CFI’s mission is to help wounded service members return to function, either in active duty or with a civilian lifestyle in medical retirement. It combines technologically advanced treatments with fun stuff, such as paintball and a wave pool.

Smith, who was given special clearance to rehab at the facility, was a candidate for its recovery program because of the seriousness of his injury, which required 17 surgeries to address a serious infection and resembled those suffered in combat.

“Alex’s injury was not just a run-of-the-mill tibia fracture,” said Matthew Schmitz, the chair of orthopedics at the CFI. “After the infection set in, it was truly like the blast injuries that we see in wartime trauma. … And then the rehab part of it afterward, that’s why the CFI was invented.”

Smith, who first mentioned the idea of returning to football to the head team physician, Robin West, during an exploratory visit to the CFI, made San Antonio his second home early last year, traveling from Northern Virginia on Monday and returning to his family on the weekend for roughly six weeks. His treatment was intended to have no bounds and was arranged so he would feel not like a famous athlete but like a normal person.

It also included another crucial component: White. He already had completed nearly a year of the CFI’s “Return to Run” program, which included a brace called the Intrepid Dynamic Exoskeletal Orthosis (IDEO) that White hopes will eventually allow him to return to active duty. But he was asked to stay on to act as a mentor for Smith.

The men may have seemed different on the surface — Smith is a 6-foot-4 quarterback, and White is a muscular military veteran who is several inches shorter — but their injuries and recoveries were eerily similar. The physicality of their jobs was unlike most, and they had expectations that matched.

“You come back from a catastrophic injury, and you try to get back to an elite level like he is, and we’re kind of the same as far as our jobs in the military,” White said. “To be able to do that side by side and feed off of each other was very critical in me staying motivated as well.”

Smith and White became close friends at the Center for the Intrepid. White still jokes about the time he beat Smith in a footrace during their recovery. (Courtesy of Chris White)

Smith and White became close friends at the Center for the Intrepid. White still jokes about the time he beat Smith in a footrace during their recovery. (Courtesy of Chris White) The workdays began at 7 a.m. and typically ended around 3 p.m., White said. They would usually start with an hour-long session of blood-flow restriction training that combines controlled blood flow with low-intensity exercise to improve muscle strength.

Afterward, the two would head to Charro Mexican Grill, a small taco shop a few miles away, for breakfast burritos.

“We’d literally go every morning because he loved them so much,” White said. “And he can eat — a lot.”

The rest of their day was usually filled with cardio, maybe some pool training and core stabilization work, and plenty of time on the field behind the CFI. That was where Smith would rediscover his rhythm of dropping back and moving up in the pocket — with White serving as Smith’s top receiver. Unfortunately, White’s route-running left something to be desired.

“It’s pretty terrible, actually,” White said. “I just asked him, ‘What do you want me to do?’ And he’d say, ‘Just run that way.’ ”

There was also trash-talking, White said, often by Smith. (“There was one time he kept making short jokes,” White said, “so I challenged him to race, and he got smoked.”) And White came away surprised by how down to earth he found the NFL veteran to be.

“It was quickly apparent how humble he truly was and how much he truly cared about other people,” White said. “I’m very blunt, and honestly, I just don’t care who you are or what your status is. That was another reason why they kind of reached out to me because they knew I would treat [Smith] just like anybody else. It’s very important for someone’s recovery to feel human. And, to be a celebrity, I can only assume he doesn’t get to feel like that very often.”

“Everybody is put on this planet to do one thing,” White said, “and I truly believe that mine is to serve this country and to protect everybody in it.” (Matthew Busch for The Washington Post)

“Everybody is put on this planet to do one thing,” White said, “and I truly believe that mine is to serve this country and to protect everybody in it.” (Matthew Busch for The Washington Post) ‘It truly inspires you’

Smith’s program was cut short by the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in early March, and over the course of the past several months he has completed his return to the field — first being cleared to rejoin Washington’s roster, then seeing his first game action in October and finally taking over as the team’s starter and leading a run that led to last week’s division championship. He is expected to start Saturday night’s playoff game, even as he deals with a calf strain in his surgically repaired leg.

White is now nearly four months into attempting his own comeback. In March 2019, he was fitted for the IDEO brace, which, in conjunction with the CFI’s treatment regimen, helped him finally run again, nearly eight years after his injury. He is hoping to have his medical retirement reversed so he can return to active duty with the IDEO brace.

When asked how rare it is for a service member to seek a reversal of retirement, White paused.

“Well, I put it to you like this,” he said. “When I brought it up, everybody kind of looked at me sideways. It’s hard to get somebody to understand. It’s hard for me to get my family — and even myself sometimes — to understand why.”

Not solely because of what he suffered physically but also because of the benefits and monthly payments he would forfeit if he were approved to return to duty.

“It’s hard to wrap your head around that,” White said. “Like, why would you do that? … But everybody is put on this planet to do one thing, and I truly believe that mine is to serve this country and to protect everybody in it.”

Smith was asked the same question — why? — when he returned to the field for the first time in August. Why would he want to put his body at risk again after suffering an injury so severe it nearly cost him his life?

“You miss the edge that this game gives you week in and week out of really having to toe the line every single game day, … putting yourself out there, being accountable to your teammates, the challenge of finding a way, a formula to prepare and go out there and win, week in and week out,” Smith said this week. “… You can’t duplicate it. You get away from it, and you miss it quick.”

Smith’s comeback has propelled Washington to the playoffs. (John McDonnell/The Washington Post)

Smith’s comeback has propelled Washington to the playoffs. (John McDonnell/The Washington Post) Smith’s comeback probably would not have been possible without his drive and perseverance, but Smith has credited the CFI for much of his inspiration in wanting to return to football — and for feeling as if he could actually do it. As a show of gratitude, Smith recently began a clothing collection with brand Attitude is Free and is donating all proceeds to the CFI.

He and White also gained an enduring friendship. They still talk or text multiple times a week, discussing each other’s family, their lives and, occasionally, football.

And Smith always asks for an update on White’s comeback.

“His journey being parallel to mine, it truly corrects me every day,” White said. “… To see how focused he stayed and to know that, as long as I continue to persevere, whatever is supposed to happen is going to happen — it’s the mind-set he had to keep.

“You know what he’s going through, being through it. I think about what he has to go through in a game, and it truly inspires you.”