Hurrah for the end of buck-passing (hopefully)

The outgoing administration’s approach, Deese said, “has essentially been to leave everything to the states and not take any action to try to address those issues of clarity or otherwise.”

“A lot of the failures are derivative of that,” he added — which is undoubtedly correct.

President “I Alone Can Fix It” Trump has, perversely, absolved himself of responsibility for anything. He explicitly said last March that “I don’t take responsibility at all” for flaws in the coronavirus response, including persistent testing shortages. Likewise, at a March meeting with business leaders pleading for federal leadership as states bid against one another for supplies, Trump’s son-in-law and adviser Jared Kushner reportedly said: “That’s their problem.”

Fast-forward to Trump tweeting last month, “The Federal Government has distributed the vaccines to the states. Now it is up to the states to administer. Get moving!”

Even before the coronavirus hit, the Trump administration (aided by congressional Republicans) had been trying to dump intractable health-care problems onto states that were ill-equipped to solve them alone.

Trump prefers passing the buck to the states because actually trying to fix big problems is hard. He might fail; safer to let someone else attempt it (and then swoop in to take credit if they succeed). His fellow Republicans presumably went along for a different reason: The strategy is consistent with the party’s longtime approach to federalism. One man’s “passing the buck” is another man’s “states’ rights,” after all.

Relying upon states to serve as the “laboratories of democracy” has its upsides, of course. During normal (non-crisis) times, states can experiment with different ways to deliver services, tax, regulate, train workers or whatever else. Researchers and policymakers study what succeeds and what doesn’t.

But there’s a degree of fantasy involved in thinking that states — with their much more limited resources and often part-time legislatures and smaller public-health agencies — are equipped to figure out how to respond to a sudden, logistically complex pandemic without much federal guidance. Especially if this lack of coordination results in states simply competing against each other for scarce supplies (and bidding up their prices), rather than finding ways to create more of those supplies — or issuing contradictory safety guidelines. Arguably, this is the case with inconsistent mask and social distancing mandates across porous state borders. Some states’ efforts effectively canceled each other out.

Some states have responded to these challenges by passing the buck even further down the line.

Consider Florida’s vaccine rollout. When the feds declined to provide sufficient clarity for distribution, Florida chose not to fill the leadership vacuum. No one was in charge. The state essentially left decisions up to hospitals, which led to chaos and confusion and seniors sleeping in their cars outside public health centers to queue for shots.

There are also economies of scale that come with centralizing decisions at the federal level, and not only for administering health-related services, either.

Another serious flaw of our federalist system exposed by the pandemic is our fragmented safety net. There are more than 50 separate unemployment insurance systems — each designed, commissioned and maintained by a different state, district or territory. The main thing most have in common is their awfulness. By which I mean they’re generally arbitrary, confusing, painful to access and expensive for states to maintain. Right now, they’re also (not coincidentally) extremely backlogged.

Having the federal government develop and administer a single user-friendly interface, with minimum requirements for generosity — as is the case for some other benefits created under federal law, such as Social Security — would be far simpler for users and states. It would probably be collectively cheaper for taxpayers, too, because states wouldn’t have to develop and maintain duplicative benefit systems.

A risk of nationalizing more of these kinds of programs, of course, is that we could wind up with a really incompetent federal government in charge of everything. (This is not exactly a hypothetical.) So, maybe it’s good to diversify some risk away from the feds.

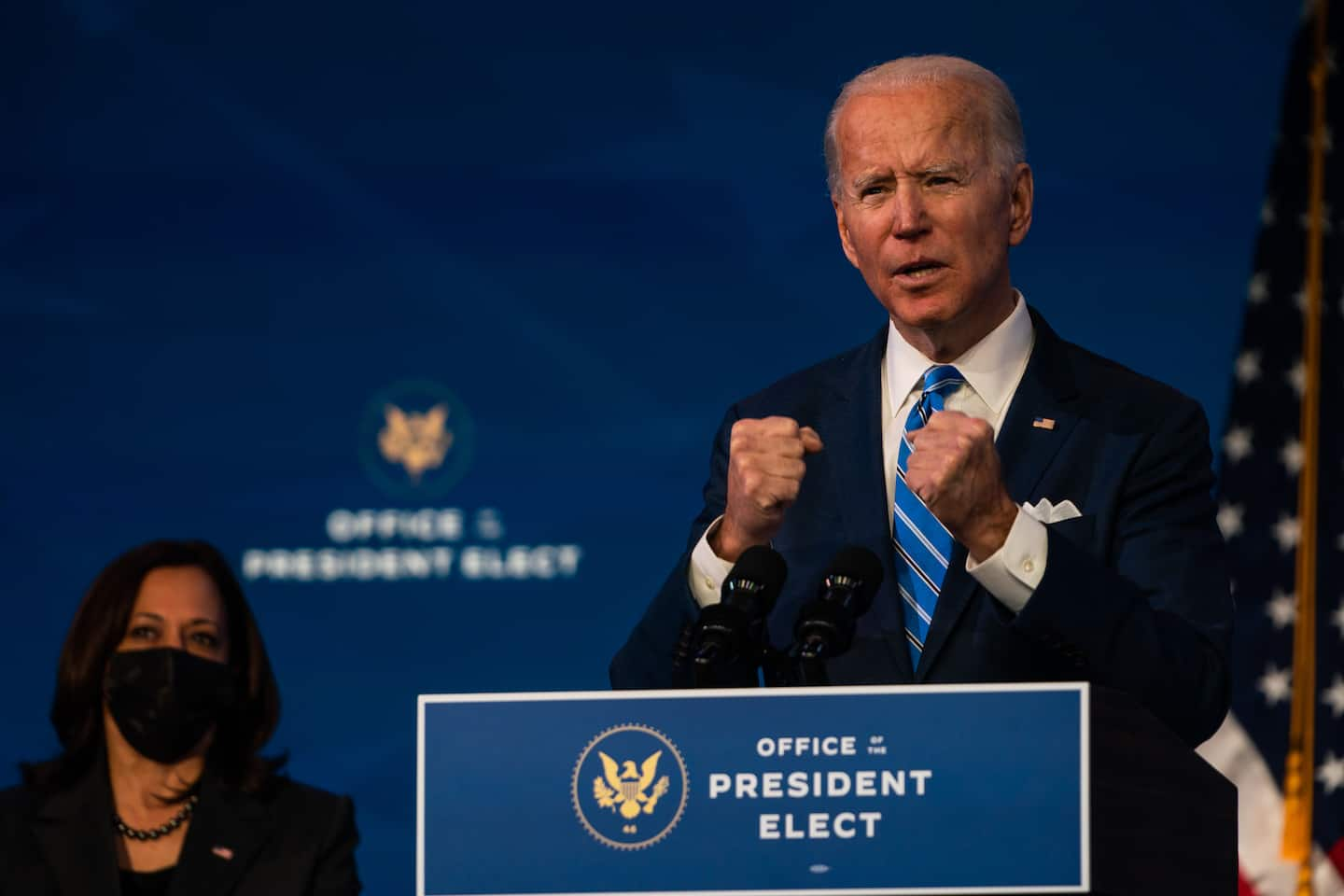

Even so, it will be comforting to have a presidential administration that not only sees the possible advantages of centralizing leadership but is willing to take on the hard work (and risks) of providing it. Like Trump, Biden and his advisers know they could fail. Yet they’re willing to assume the burden of responsibility that comes with trying, rather than cravenly declaring every challenge to be someone else’s problem.

During Friday’s call, Deese concluded by saying that “ultimately, states and localities have a huge role to play in this. But federal government needs to be providing clear, consistent and more guidance, more logistical support and more resources.” In many ways, that’s a pretty banal statement. But in the context of the past four years, it’s practically revolutionary.

Read more: