The ‘whitewashing’ of Black Wall Street

TULSA — When Guy Troupe returned to his hometown after a career in sports consulting to open a coffee shop, he envisioned a gathering spot for Black business owners who would resurrect the commercial district so prosperous that it became known as “Black Wall Street.”

New businesses are indeed rising all around Tulsa’s historic Greenwood district: The Vast Bank headquarters features a French sidewalk bistro and a rooftop sushi bar. Across the street from Troupe’s cafe, cranes hover over the construction of an office and retail complex and a $20 million museum dedicated to that early paragon of Black enterprise — and a century-old massacre that obliterated it.

But as Tulsa authorities provide millions in financial incentives to revitalize the district ahead of an anticipated influx of tourists for this year’s centennial of the 1921 bloodshed, Black entrepreneurs say they are being threatened with erasure yet again, shut out of Greenwood’s most prestigious development projects and priced out of prime retail locations.

Barista Angel Jamison talks with Yvette Troupe, an owner of the Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge coffee shop, whose name is an homage to the successful Black business district destroyed a century ago. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Barista Angel Jamison talks with Yvette Troupe, an owner of the Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge coffee shop, whose name is an homage to the successful Black business district destroyed a century ago. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) Some $42 million in city tax incentives and loans — race-blind under Oklahoma law — has largely benefited White-owned firms that won the majority of contracts to develop lucrative parcels closest to downtown, according to city officials and business leaders.

Tulsa officials say the city has just begun paying attention to the dearth of Black property ownership and will soon open up more land for redevelopment, north of the interstate and farther from the central business district. But it is already too late to make a difference in the most desirable part of Greenwood.

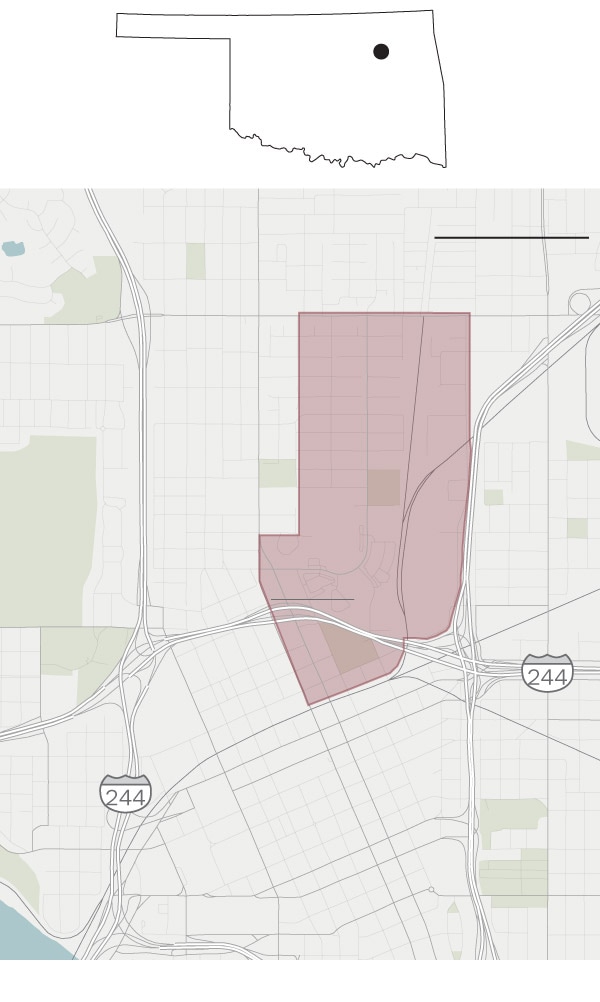

E. Pine St.

N. Greenwood Ave.

MLK Jr. Blvd.

L L Tisdale Pkwy

Historic

Greenwood

District

Tulsa

Country

Club

OSU

Tulsa

campus

E. 11th St.

Source: Maps4News/HERE

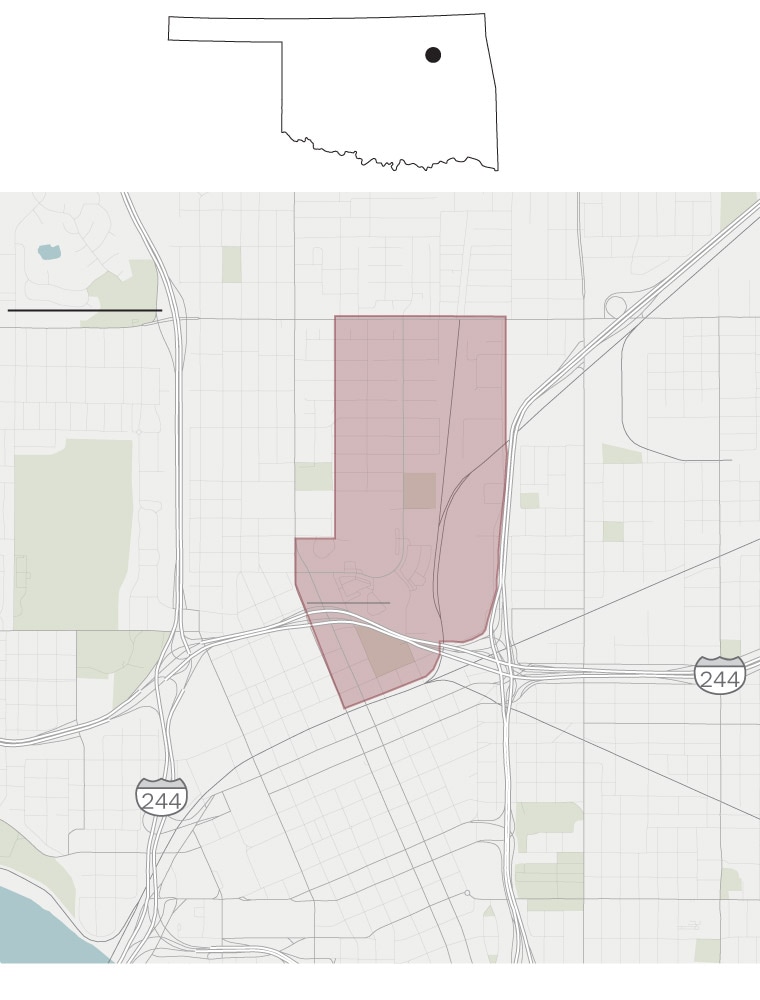

E. Pine St.

N. Greenwood Ave.

MLK Jr. Blvd.

L L Tisdale Pkwy

N. Utica Ave.

Historic

Greenwood

District

Tulsa

Country

Club

OSU

Tulsa

campus

E. 11th St.

Source: Maps4News/HERE

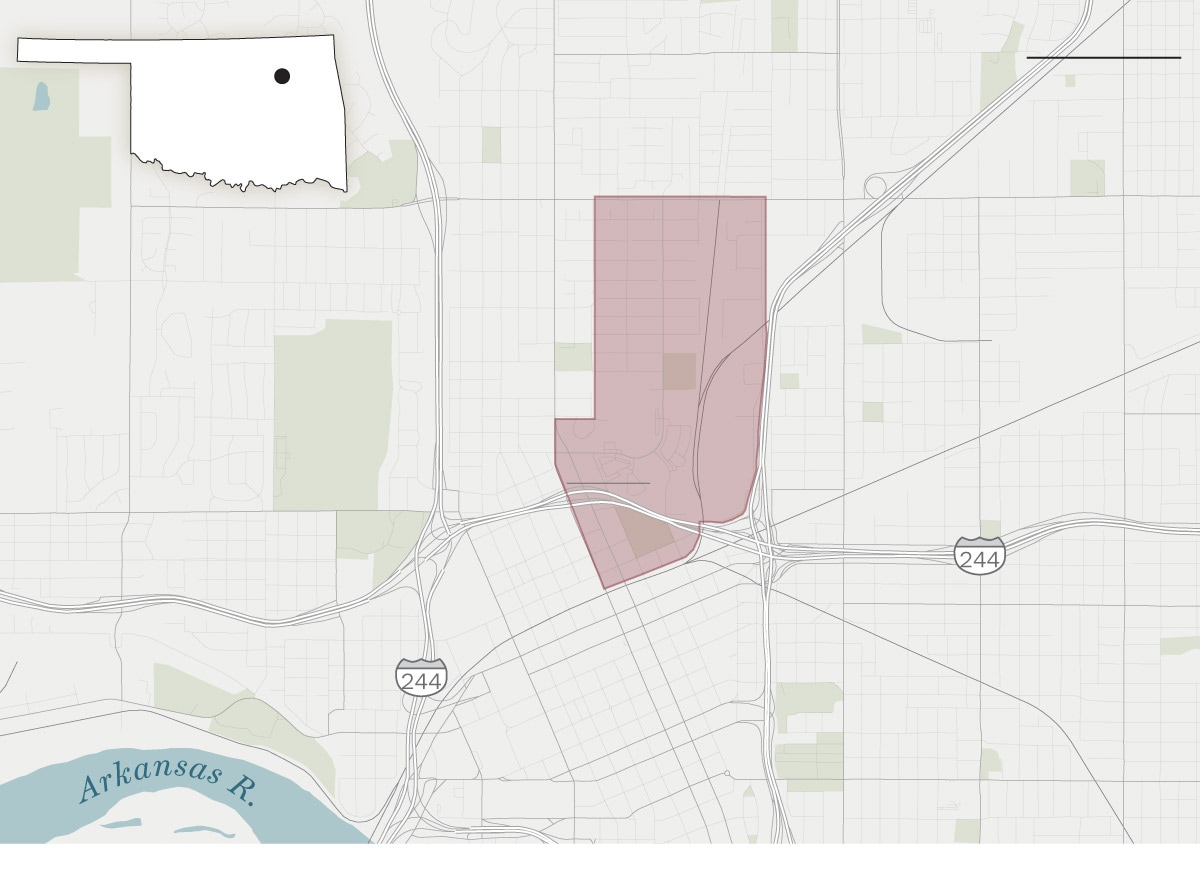

E. Pine St.

N. Greenwood Ave.

MLK Jr. Blvd.

W. Newton St.

L L Tisdale Pkwy

N. Lewis Ave.

N. Utica Ave.

Historic

Greenwood

District

Tulsa

Country

Club

OSU

Tulsa

campus

W. Edison St.

E. 11th St.

Source: Maps4News/HERE

Black entrepreneurs say they have been reduced to renters where African Americans once owned land and built a thriving business community. Without property ownership, they face more difficulty seeding generational wealth. Only a one-block commercial stretch south of the interstate remains Black-owned. To Troupe, it feels like “the final execution of a plan” set in motion a century ago when White Tulsans destroyed what was then seen as a powerful symbol of Black economic success.

The massacre in Greenwood was part of a wave of violence unleashed against Black communities across the country by White mobs in the early 20th century, generally with the approval of local governments.

[‘They was killing black people’: A century-old race massacre still haunts Tulsa]

People in Tulsa’s historically Black Greenwood district achieved much economic success before 1921. (Greenwood Cultural Center)

Greenwood was left in ruins after the 1921 massacre. (Library of Congress)

LEFT: People in Tulsa’s historically Black Greenwood district achieved much economic success before 1921. (Greenwood Cultural Center) RIGHT: Greenwood was left in ruins after the 1921 massacre. (Library of Congress)

White Tulsans murdered scores of African Americans and destroyed nearly $2 million in property ($29 million in today’s dollars), a conservative estimate based on insurance claims and lawsuits filed against the city after the massacre, according a 2001 state investigation. No Black property owners were compensated, and neither the city nor state government committed money toward rebuilding Greenwood in the immediate aftermath.

Now, as activists across the country mobilize around reparations to atone for slavery and its legacy of systemic discrimination against African Americans, some Black Tulsans are demanding restitution for the massacre, the theft of Black wealth and government barriers to rebuilding. A lawsuit filed by descendants and a survivor in September accuses city, county and business leaders of continuing to enrich themselves at the expense of the Black community by “appropriating” the massacre for tourism and turning Greenwood into a “primarily White-owned commercial hub.”

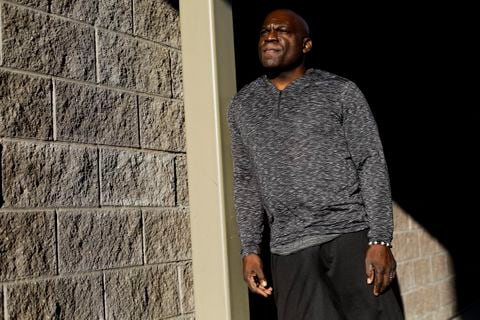

Meaningful redress must economically benefit Black Tulsans, said Troupe, who is not part of the lawsuit.

“It’s hard to stomach the idea that a museum and tourism will fix the challenges of systemic racism. I came to take back what’s rightfully ours,” said Troupe, 54. “Who owns in there? It’s not us. The only thing we own are homes. But big industrial buildings, lands zoned for commercial development? We don’t have it.”

For entrepreneur Guy Troupe, meaningful redress for the injustice of the past must economically benefit Black Tulsans. That means land ownership. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

For entrepreneur Guy Troupe, meaningful redress for the injustice of the past must economically benefit Black Tulsans. That means land ownership. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) Much of the more than 35 square blocks of homes and businesses that made up Greenwood are now owned by the city, the Tulsa Development Authority and the state university system. The Black-run Greenwood Chamber of Commerce owns the block-long commercial stretch of 10 brick buildings rebuilt in the aftermath of the massacre.

Those buildings, housing mom-and-pop businesses, are penned between the interstate to the north, large new commercial and residential developments to the south and a minor league ballpark to the west, with more development planned on a former industrial zone to the east.

The city has incentivized more than a dozen projects in and around Greenwood over the past decade, according to data provided by the city, including USA BMX’s national headquarters and arena, which officials say will draw more tourists when it opens this year. The Tulsa Development Authority has sold a half-dozen prime parcels of land to private developers.

But few Black developers have the capital, credit and connections of their White counterparts.

“That’s what limits the participation of people of color — not any policy or bias on the part of the TDA or the city,” said Jot Hartley, general counsel for the Tulsa Development Authority. “Some of these projects have been rather large and required capital that’s not ordinarily available to just anybody unless they are already in the business of developing large projects.”

When Michael E. Smith, a Black Houston-based developer born and raised in Tulsa, presented a proposal for a seven-story office building on land that later became the Vast Bank headquarters, the contract ultimately went to a well-known White developer whose firm had not participated in the first round of bidding but had a deep downtown portfolio.

“That hurt me to the core. Certain public entities don’t feel like minority vendors could produce or deliver,” said Smith, 63. “Until the community gets some demonstrated wins — i.e., projects up and running to show the value of developers of color — that is going to be the prevailing mind-set in Tulsa.”

Smith said he did win the conditional rights to redevelop the site of a historic African American hospital on the northern edge of Greenwood, a mile and a half past the interstate. His only competitor: another Black developer. He said he’s in the final stages of securing funding for the project.

City officials say they are trying to create opportunities for Black entrepreneurs, such as a new program preparing small firms to compete for multimillion-dollar projects by helping them gain development expertise.

[Reparations mean more than money for a family who endured slavery and Japanese American internment]

Black entrepreneurs say they have been reduced to renters where African Americans once owned land and built a thriving business community. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Black entrepreneurs say they have been reduced to renters where African Americans once owned land and built a thriving business community. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) “We want to ensure space to allow Black Tulsans to take advantage of the tourism opportunities that will be created,” said Kian Kamas, Tulsa’s chief of economic development. “There is a fervent commitment to ensuring that Black-owned businesses have an opportunity to be a part of that revitalization.”

Kamas said the city plans to develop 55 additional acres on smaller parcels north of the interstate — “a huge redevelopment opportunity” she said the city will actively promote among Black developers. One request for proposal requires applicants to specify how their projects would honor the legacy of Greenwood.

The Tulsa Development Authority says it considers a developer’s ties to the community, along with experience and financing, when evaluating proposals, but it is barred from considering race in its decision.

“The city recognizes the history of land-taking in the area and is very sensitive to the need to go through an intensive process to give the community an opportunity to provide input for what that will look like,” Kamas said.

She acknowledged that the city failed to intervene before much of Greenwood passed into White ownership: “We’re in new territory. Historically, the city hasn’t even attempted to try to focus on those goals.”

“Everybody has a heightened awareness now of racial dynamics and inequity, and there’s a growing demand to change that and do so much more rapidly,” she said. “We recognize that shortcoming and want to find ways to remedy it to the best extent possible within the confines of our current legal framework.”

Economists who study race and public policy say it is impossible to fix ingrained racial inequalities with race-neutral practices. Policies that fail to consider race only cement existing disparities, they said.

“There is no such thing as race-blind economic development,” said Darrick Hamilton, a professor of economics and urban policy at The New School in New York. “Capital itself positions people and businesses to better take advantage of economic development. And we have a history in which whatever capital Black people would have amassed was literally massacred in a terrorist uprising 100 years ago.”

Without factoring in corrective policies, government officials are not truly recognizing the continuing harms of the massacre, economists say.

“To the extent that race was used as a criteria for the exclusion and depression of Black achievement, how do you not use race as a corrective?” said William Darity Jr., a Duke University professor whose research focuses on the economics of reparations.

LaToya Rose, a tax strategist with longtime ties to Greenwood Avenue, chats with other patrons at Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge, which serves as a hub for Black business owners and aspiring entrepreneurs. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

LaToya Rose, a tax strategist with longtime ties to Greenwood Avenue, chats with other patrons at Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge, which serves as a hub for Black business owners and aspiring entrepreneurs. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) Troupe has a personal connection to Greenwood Avenue. A block from where his coffee shop, Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge, opened on New Year’s Day in 2020, his great-aunt ran a salon and beauty school in the late 1940s and early ’50s that was affiliated with the company started by Madam C.J. Walker, widely considered to be the United States’ first female self-made millionaire.

Troupe, who had led the National Football League’s first corporate diversity council, said he regularly sought to buy property from the Tulsa Development Authority as well as private landowners over the past 15 years but could never negotiate a deal he considered to be fair.

“Two or three powerful groups own the land, and I’ve tried to forge a relationship with them to no avail,” he said. “The only relationship they want is to lease. There is no offer of equity.”

So when he and his wife, Yvette, a biotech sales consultant, returned to Tulsa to start the Liquid Lounge, he said they had little choice but to “rent in a gentrified neighborhood from landlords who don’t look like us.”

They chose a $1,500 month-to-month lease in the GreenArch building, a retail and apartment complex developed by Kajeer Yar and his wife, Maggie Hille Yar, who are also developing the office and retail complex across the street.

Maggie Hille Yar, who is White, helps lead economic development for the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission. When the commission’s initial location for a center dedicated to Greenwood’s history fell through, her family’s Hille Foundation donated a third of an acre for the Greenwood Rising museum to be built next to their office and retail project.

The Yars say they strive for their developments to be the “21st-century version of Black Wall Street,” naming Black tenants in GreenArch, including a yoga and spin studio, a sneaker boutique, an art gallery and Troupe’s coffee shop.

“While we are the landowners, we have always taken great pains toward including a balanced and diverse mix of tenants,” said Kajeer Yar, an immigrant from Afghanistan who grew up in Tulsa. “We said, ‘Look, let’s have a tenant base that’s not only reflective of Greenwood’s past but also provides amenities for its future.’ ”

At the Liquid Lounge, Troupe tries to evoke the spirit of the legendary Black Wall Street, with frappés and teas named after O.W. Gurley, the real estate developer who in the early 1900s purchased 30-some acres in Greenwood and sold them to other African Americans; J.B. Stradford, another community pillar whose Stradford Hotel became one of the largest Black-owned businesses in Oklahoma; and Loula Williams, who, with her husband, John, owned the famed Dreamland Theatre, along with a three-story building that housed a confectionary as well as offices rented to doctors, dentists and lawyers.

Even amid the coronavirus pandemic, Black business owners and aspiring entrepreneurs gather at Troupe’s cafe six days a week, setting up virtual offices on the round tables.

Shari Tisdale gives a one-minute elevator pitch of her online clothing boutique to Kode Ransom, Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge media and content manager, for the “Greenwood Minute,” a project he is producing to promote Black businesses. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Shari Tisdale gives a one-minute elevator pitch of her online clothing boutique to Kode Ransom, Black Wall Street Liquid Lounge media and content manager, for the “Greenwood Minute,” a project he is producing to promote Black businesses. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) On a recent afternoon, Troupe gestured to a blank wall and told an insurance broker of his plans to put up a video screen and stream ads showcasing Greenwood’s Black-owned businesses as a kind of digital bulletin board — at no charge.

“This really is the way that Black Wall Street functioned. Part of it was just barter and trade. Everybody didn’t have capital,” Troupe explained. “This is what we have to do as a community to make it.”

But as much as Troupe believes in the promise of Black Wall Street — so much so that he and his wife have incorporated as BWS Enterprises — the owners of the Liquid Lounge, like other businesses here, face a dilemma: stay and pay rent in gentrifying Greenwood or find another location?

A block north of the Liquid Lounge, other Black business owners are skeptical they will benefit in any significant way from Greenwood’s redevelopment. After all, they said, the 2010 opening of the minor league ballpark, the first major commercial development in a generation, did not bring prosperity — even though the Greenwood Chamber of Commerce had required an entrance directly off Greenwood Avenue in an effort to funnel fans past Black businesses. The gate, one of five, lies beneath a highway overpass.

ONEOK Field, home to the Tulsa Drillers minor league baseball team, stands next to the one-block commercial stretch of Greenwood that remains Black-owned. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

ONEOK Field, home to the Tulsa Drillers minor league baseball team, stands next to the one-block commercial stretch of Greenwood that remains Black-owned. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) “We looked at it as an inherent marketing opportunity for Greenwood. Knowledge of its history was almost nonexistent, especially among the White part of town,” said Reuben Gant, the chamber’s former leader. “We did our job by providing the foot traffic.”

Some of the 32 Black-owned businesses leasing space from the Greenwood Chamber say they are being overshadowed by all the new development.

Since the stadium opened, “it has started to look like the whitewashing of Blacks out of Greenwood,” said LaToya Rose, a 34-year-old tax strategist on Greenwood Avenue, where her family has held a presence for three generations. Her grandfather ran a speakeasy in the 1950s. Her father owns a bail bonds operation across the street from her tax firm.

Rose works at her firm, Rose Tax Solutions, across Greenwood Avenue from her father’s bail bonds business. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Rose works at her firm, Rose Tax Solutions, across Greenwood Avenue from her father’s bail bonds business. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) Rose said she was able to negotiate a rent cap on her lifetime lease from the Greenwood Chamber, but she worries that as redevelopment continues, rents will rise and drive out other longtime Black tenants.

The hair salon next door has been in Tori Tyson’s family for three generations. Tyson, 41, started working there as a shampoo assistant in high school and purchased the salon from her cousin in 2006. In the past six years, rents have doubled in the complex for many, Tyson said, forcing out a convenience store and a haberdashery. Her own rent rose from $750 a month to $1,800, which she said she negotiated down after agreeing to refrain from posting criticism of the Greenwood Chamber or the building’s deteriorating conditions on social media. Still, she said the chamber will renew her lease in only six-month to one-year increments, making it difficult to sustain a business plan.

“To me, businesses have not been able to accomplish what they should be able to accomplish — being affordable to small, Black business owners, allowing you to pay your bills, save some money, send your kids to college and open another business,” Tyson said. The chamber is “not trying to honor what Greenwood is built on.”

Tori Tyson styles Tamikka Brown’s hair at Blow Out Hair Studio, which has been in Tyson’s family for three generations. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Tori Tyson styles Tamikka Brown’s hair at Blow Out Hair Studio, which has been in Tyson’s family for three generations. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) Freeman Culver III, the Greenwood Chamber’s chief executive, said that during his two-year tenure the chamber has filled empty storefronts with 12 more Black-owned businesses, most of whom pay below-market rates. But property taxes have increased, including a special ballpark assessment, so he said he expects to raise rents over the next five years.

Tulsa City Councilor Vanessa Hall-Harper said some local Black business leaders have so little faith in the Greenwood Chamber that they established a rival organization, the Black Wall Street Chamber of Commerce, in 2018. They are raising money to buy back land from the city.

“We want that land returned to its original use of entrepreneurship, in the spirit of maintaining the legacy of Greenwood,” Hall-Harper said. “We need to have Black developers, as opposed to letting the good old boys determine what happens in this city. It boils down to opportunity.”

A historical marker about the 1921 Tulsa massacre stands outside Vernon A.M.E. Church, which was almost entirely burned in the violence.

A faded mural sits underneath Interstate 244 along Greenwood Avenue.

Bricks from businesses that were burned during the 1921 massacre have been preserved. (Photos by Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

TOP: A historical marker about the 1921 Tulsa massacre stands outside Vernon A.M.E. Church, which was almost entirely burned in the violence. BOTTOM LEFT: A faded mural sits underneath Interstate 244 along Greenwood Avenue. BOTTOM RIGHT: Bricks from businesses that were burned during the 1921 massacre have been preserved. (Photos by Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

What took the Black community years to build vanished overnight. From May 31 to June 1, 1921, White rioters — many deputized by the police — descended upon Greenwood, gunning down Black residents, looting and torching their homes and businesses, after the White-owned Tulsa Tribune falsely reported that a Black man, a 19-year-old shoe shiner, had sexually assaulted a 17-year-old White female elevator operator.

Historians estimate that between 100 and 300 people were killed, the majority of whom were Black. Scores lost their businesses. Nearly the entirety of Tulsa’s Black community of 10,000 was left homeless, forced into internment centers under armed guard and freed only when a White person vouched for them. No White Tulsan was ever prosecuted for the crimes.

In the days following the massacre, the Tulsa Tribune ran an editorial calling Greenwood a “cesspool” and declaring that it must never be rebuilt. City leaders blamed Black Tulsans for the death and destruction, and revealed plans to purchase burned properties in Greenwood and relocate Black residents farther from downtown. The city passed an ordinance requiring the use of expensive fireproof material to make it cost-prohibitive for people who had lost everything to rebuild. Black residents sued, the ordinance was declared unconstitutional, and those who did not flee for their lives eventually rebuilt Greenwood at their own expense.

The displacement of Black people from Greenwood did not end with the massacre. In the 1960s and ’70s, federally funded “urban renewal” programs led to the demolition of Black homes and businesses for highway construction that also cut off the Greenwood commercial district from its residential neighborhoods. Some of that cleared land became the Tulsa campuses for Oklahoma State and Langston universities.

[In Syracuse, a road and reparations]

Bobby Eaton Sr. often chats with tourists visiting Black Wall Street, informing them of Greenwood’s history. “Nobody told them of the greatness that had been destroyed,” he said. “What would Greenwood have been like had the disaster not taken place?” (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Bobby Eaton Sr. often chats with tourists visiting Black Wall Street, informing them of Greenwood’s history. “Nobody told them of the greatness that had been destroyed,” he said. “What would Greenwood have been like had the disaster not taken place?” (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) “What most folks know as urban renewal, I call Negro removal,” said Bobby Eaton Sr., an 85-year-old entrepreneur known around Greenwood simply as “Pops,” whose father owned a barber shop here and whose son Dwight Eaton is Troupe’s business partner. “The only thing is now, people are not being killed, but economically, they are being assassinated.”

Black families today have just over one-tenth the wealth of the typical White household — a gap that Darity, the economist, said originated with the failure of the government to provide African Americans with 40-acre land grants that they were promised as restitution for their enslavement while giving 1.6 million White families 160 acres under the Homestead Acts enacted during and after the Civil War. The wealth disparity was exacerbated by the massacres that occurred during the Jim Crow period, he said, resulting in not only the loss of Black lives but the “destruction and appropriation of Black property by White terrorists.”

A commission appointed by the Oklahoma legislature to investigate the Tulsa massacre issued a 200-page report in 2001 recommending that reparations be paid for the lives and property lost. It also recommended that a “development enterprise zone” be established.

“The hope for me was to be able to see African Americans take hold and be back in the community again with businesses and ownership,” said former state senator Maxine Horner, 88, who helped create the commission and whose father owned a dry cleaners in Greenwood. “It hasn’t happened yet.”

Reparations to survivors and their descendants were never paid. Instead, the Oklahoma legislature passed a law to “facilitate the redevelopment of the Greenwood area” and presented each survivor with a gold-plated medal bearing the state seal. A 2003 lawsuit for reparations brought by survivors against the city and state authorities was dismissed, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

Instead of inheriting Greenwood’s wealth, Black Tulsans inherited “neglect, indifference and a century of obstruction and systemic racism from the city of Tulsa to prevent the rebuilding of Black Wall Street,” said Damario Solomon-Simmons, the Tulsa civil rights attorney heading the lawsuit filed in September.

The government should rectify the economic racial disparities it helped create over the past century, he said. Today, Black Tulsans are more than twice as likely as Whites to be unemployed, according to Census Bureau data. A third of Black Tulsans live in poverty, compared with 12 percent of White Tulsans. And the typical Black family in Tulsa has a net worth of $8,000, compared with $145,000 for a typical White family, according to research by Darity and Hamilton using 2014 data.

A building under construction in Greenwood, which will feature office, retail and restaurant space. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

A building under construction in Greenwood, which will feature office, retail and restaurant space. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) “In the historical Greenwood district, large corporations and rich White folks are building high-rises and condos not benefiting the original owners of Greenwood, their descendants or the larger Black population pushed into north Tulsa,” Solomon-Simmons said. “The exact same entities that destroyed Greenwood and perpetrates the continuing harm to Greenwood are now benefiting by selling the brand of Black Wall Street to the world.”

He accused the city of promoting “cultural tourism” for visitors to “come and walk around what really is nothing because historic Greenwood doesn’t really exist anymore.”

“How does that lessen the wealth gap? How does that put money back into the pockets of the individuals who lost money, power, assets? It’s actually worse to acknowledge the massacre and do nothing to fix it.”

While the city has dedicated museums and memorials to the massacre — with the mayor, a White Republican, ordering a search for mass graves — and renamed a downtown thoroughfare originally honoring a city founder and Ku Klux Klan member to Reconciliation Way, the idea of reparations is met with broad resistance. The city, the Tulsa Development Authority and other defendants have responded to the lawsuit with motions to dismiss.

“I do not believe this generation of Tulsans should be financially punished for the illegal acts of criminals a century ago,” Mayor G.T. Bynum said in a statement. He said he campaigned on addressing long-standing racial disparity in Tulsa and is focused on economic development in “historically overlooked” neighborhoods such as Greenwood.

Patrons dine at Wanda J’s Next Generation soul food restaurant. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Patrons dine at Wanda J’s Next Generation soul food restaurant. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) On Greenwood Avenue, Tyron Walker, owner of Wanda J’s Next Generation soul food restaurant, wishes folks would stop focusing on the past.

“To be hung up on that reparations and race stuff really keeps people divided,” said Walker, a Black Republican Trump supporter who ran unsuccessfully for mayor last year. He tells his six daughters who help in the family restaurant, “Don’t get mad at the system. Operate within it.”

When Walker’s rent doubled in 2018, he decided to save up in hopes of buying his own property — outside of Greenwood.

“Eventually, this place will run its course,” he said. “If you don’t own it, they dictate to you what you do.”

Down the street at his cafe, Troupe said an “economic stimulus” package for Black entrepreneurs to create a new Black Wall Street elsewhere may be more politically palatable than reparations.

Since the most valuable land closest to downtown has all been “sold or hoarded,” Troupe said the city could make the remaining parcels north of the interstate affordable to Black business owners “by deeding land, providing grants and offering low-interest loans so the atrocities of the past could be addressed.”

“Historical Black Wall Street is gone. It’s dead,” he said. “But its spirit can be revived.”

The Rev. Robert R.A. Turner, right, the pastor at Vernon A.M.E., leads a protest in support of reparations through downtown Tulsa. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

The Rev. Robert R.A. Turner, right, the pastor at Vernon A.M.E., leads a protest in support of reparations through downtown Tulsa. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) On a recent Wednesday afternoon, just as he has every week for the past two years, the Rev. Robert R.A. Turner marched through downtown Tulsa, flanked by more than a dozen protesters carrying signs that said, “Reparations Now.”

They filed past loft apartments in the rebranded “Arts District” on the western edge of Greenwood, past the Tulsa Drillers baseball stadium that Turner said should be renamed the “Tulsa Killers” because White Tulsans “literally got away with murder” and under the interstate toward Turner’s church, Vernon A.M.E., which was almost entirely burned in 1921.

“This is all Greenwood,” Turner shouted through his bullhorn as the sun began to set. “This is no mere tourist destination. This is a crime scene!”

Along the way, they stepped over plaques embedded in the sidewalks that commemorate lost Black-owned hotels, theaters and doctor’s offices. One of them pays tribute to Nails Brothers, a shoe and record store that belonged to Brenda Nails-Alford’s grandparents. The plaque, listing the store’s address as 121 1/2 N. Greenwood Ave., lies a few feet from the highway overpass. “Destroyed 1921,” it reads.

Her grandparents, who also owned a dance pavilion and skating rink, as well as a taxi service, rebuilt their business after the massacre but never amassed the same level of wealth. Her grandfather, a college-educated shoemaker, suffered mental and emotional setbacks, leaving her grandmother to raise four children on her own. To survive, she ended up working as a domestic servant for a White family.

“If we had been able to receive some sort of reparations, we could be more of a partner in the revitalization going on right now,” said Nails-Alford, a career services coordinator. “But because we lost that economic advantage and it was never replaced, we don’t have those seats at the table.”

Brenda Nails-Alford stands next to the Black Wall Street Memorial, which lists the names of Black businesses that were destroyed during the 1921 massacre, including her grandparents’ shoe shop. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post)

Brenda Nails-Alford stands next to the Black Wall Street Memorial, which lists the names of Black businesses that were destroyed during the 1921 massacre, including her grandparents’ shoe shop. (Joshua Lott/The Washington Post) Alice Crites and Andrew Van Dam contributed to this report.