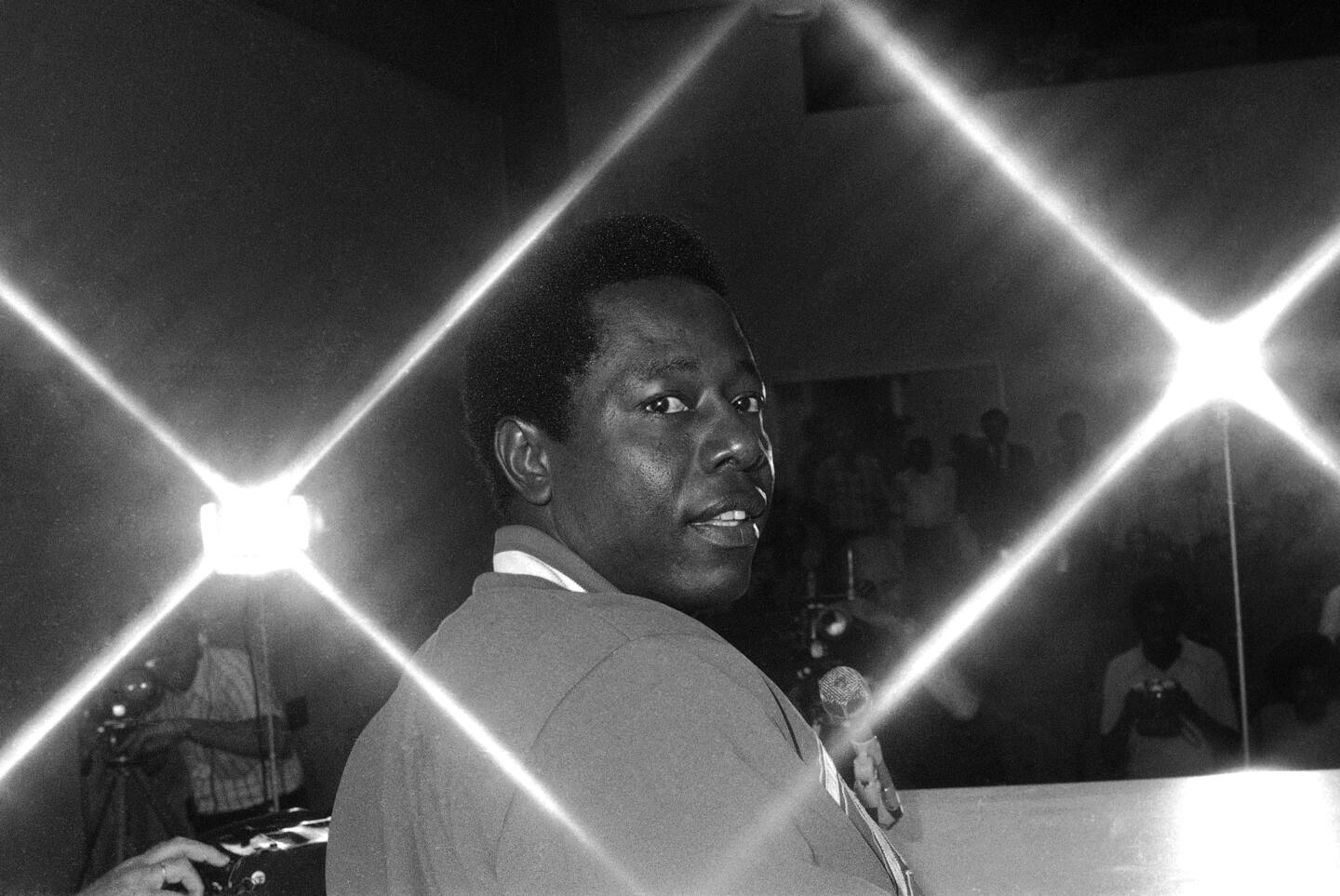

Hank Aaron fought racism the way he played: Quietly but with power

Aaron should have been able to leave this earth as he did Friday, at age 86, with fond memories of his career-defining moment: that 400-foot shot off Al Downing that pushed him ahead of Babe Ruth on the all-time home run list. The pursuit of 715 and that glorious trot around the bases as two strangers patted him on the back would have been more enjoyable if it hadn’t come with more hate mail than anyone should encounter. If he didn’t have to live in fear for his own safety and that of his family.

Hardened by death threats, a kidnapping plot of his daughter and unmentionable words thrown his direction during that historic chase, Aaron became a hero whose excellence couldn’t escape the ugliness of America’s intolerance. But through his smile, grace and dignity, he wouldn’t be broken or become bitter. He wouldn’t surrender a mission that began with a desire to use baseball as a means to leave a hardscrabble, poverty-stricken existence in Alabama and that ended with Aaron establishing a legacy that stretched far beyond the combined distance of those 755 long balls that sent him into retirement as the home run king.

“If you asked him, he told you the truth about racism,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, where Aaron’s wife, Billye, serves on the board. “He was not defined by it. He was a man at peace. If there were scars, it didn’t show. He didn’t walk into the room like, ‘I am Hank Aaron, and this is what I endured.’ That is also what made him special to me. We all want to believe and want to see people that contend with racism — as we all do — who overcome it, who played past it into their greatness but don’t lose their core. They don’t lose their center. He certainly never did.”

Aaron’s hero, Jackie Robinson, understood his purpose from the moment he broke the color barrier in 1947. The path was still uneven and wrought with resistance when Aaron made his debut with the Milwaukee Braves seven years later, but his role in advancing the civil rights struggle would play out over the next 22 years — from winning the MVP and a World Series title in 1957 to catching Babe Ruth to making the all-star team every season from 1955 to 1975 to becoming the first Black star in the Deep South.

“It still hurts a little bit inside because I think it has chipped away at a part of my life that I will never have again,” Aaron said in an interview with American History magazine in 2006. “I didn’t enjoy myself. It was hard for me to enjoy something that I think I worked very hard for. God had given me the ability to play baseball, and people in this country kind of chipped away at me. So it was tough. And all of those things happened simply because I was a Black person.”

As a 20-year-old rookie, Aaron might not have understood what he inherited from Robinson. But as he experienced more success, he never shied away from his responsibilities. To help younger players get acclimated to a sport in which the fans might not be ready to support their journeys. To be a shining example for a community that needed inspiration and representation. And to show detractors that his will wouldn’t be deterred. He remained relevant long after his career ended, serving as a trusted and respected voice on the progress — or lack thereof — for Black people in baseball and this nation. His last public gesture was receiving the coronavirus vaccine early this month, which he did to help reduce any stigmas preventing Black people from getting it.

“There was a goodness, a stillness, a sureness,” Ifill said of Aaron. “He remained a civic leader. That’s very precious for our community. His voice remained strong, and his sense of public engagement remained strong throughout his life.”

In an interview in the fall, Houston Astros Manager Dusty Baker, a former teammate and longtime friend, told The Washington Post he prayed that he wouldn’t be drafted by the Braves in 1967; a Northern California kid, Baker wanted to avoid playing in the South. But when he arrived, Aaron was there, promising Baker’s mother that he would look after him. Not only did Aaron show Baker the way on the field, he showed him how to handle the adversity that inevitably came off it.

Aaron wouldn’t burden Baker and their teammate, Ralph Garr, with all of the stresses that came from his successes. Baker would track down the hate-filled letters that Aaron balled and tossed in the trash can, curious to read the words that obviously hurt his mentor. Then he’d marvel at how Aaron continued to step into the batter’s box every day, ready to accept whatever came his way. The example Aaron set has stayed with Baker through a lifetime in baseball.

“Not to carry on with hatred but to carry on with strength. That’s what we’ve got to do,” Baker said. “That’s what I tell the brothers: ‘We’ve got to keep persevering.’ ”