Climate change is upending Lebanon’s booming business of boutique wineries

BTALLOUN, Lebanon — The autumn chill came late, descending suddenly on Lebanon with the arrival of November. The sun weakened, the fog settled in, electric heaters whirred, and the few grapes still hanging off Sarmad Salibi’s vines trembled in the wind.

Despite the cold, customers continued to fill a dozen outside tables at his Iris Domain winery. Families feasted on duck confit and pumpkin pasta as soft jazz played in the background. Bottles of red flowed. Over the past five years or so, Lebanon’s lush mountain wineries like Iris Domain have become a weekend retreat, a reprieve from the cities’ lack of greenery.

But the future of this burgeoning industry is under threat from climate change. Unanticipated temperature changes and recent disruptions in traditional rain cycles have begun upending the winemakers’ work.

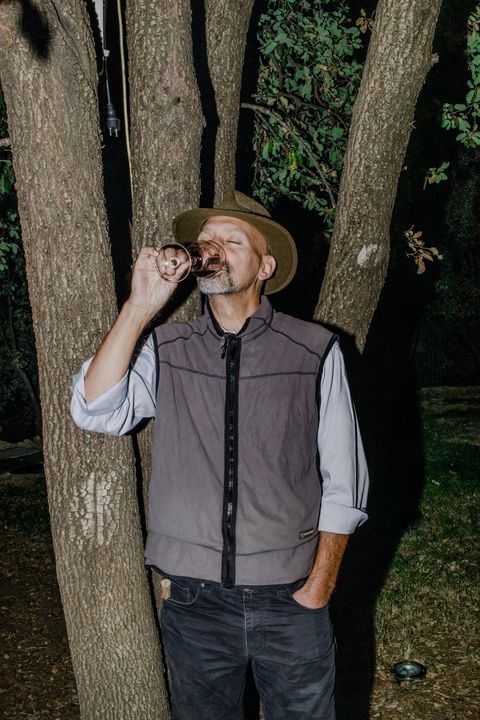

Sarmad Salibi samples his wine at Iris Domain in Btalloun. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

Sarmad Salibi samples his wine at Iris Domain in Btalloun. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post) Rainy seasons are coming earlier in the year, and this past October was the hottest on record in Lebanon, according to Rabi Mohtar, dean of agricultural and food sciences at the American University of Beirut. He attributes the shifting weather patterns to climate change, which is already testing wine industries from California to Italy and Germany.

The intense heat sharply reduced Salibi’s grape yield, wearing out the vines by the end of summer. “They’re burnt out. They need water, and we don’t water them here,” he said, noting that Lebanese viticulture relies on rain rather than irrigation.

The grapes puckered up like raisins before being picked. Those harvested later in the season were too sweet. Excessive sunshine increased the sugar in the grapes and thus the alcohol level, making them unusable.

“We couldn’t pick all my cabernet sauvignon,” Salibi said. As for many of the grapes they did pick, “we made them into molasses.”

Bottles age at Iris Domain, a weekend retreat for city dwellers. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

A lab at the Chateau Khoury winery. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

LEFT: Bottles age at Iris Domain, a weekend retreat for city dwellers. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post) RIGHT: A lab at the Chateau Khoury winery. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

A booming industry

When this country’s winery-tourism business emerged a few years ago, it attracted both Lebanese and foreign visitors to the Bekaa Valley, where most of the wineries are located. The Bekaa is an area controlled by the militant group Hezbollah and mostly populated by tribes and thousands of Syrian refugees. In the past, travelers had come to the valley mainly for its famed Roman ruins in Baalbek. Wine changed all that.

New boutique wineries found a market on social media. In this Instagram-addicted land, both young and old were allured by photos of Western food and glasses of wine set against a backdrop of overwhelming greenery and endless mountains. “We can’t believe this is in Lebanon” was a common sentiment.

This tourism has been part of a larger boom in Lebanon’s wine industry, which produces at least 8.5 million bottles a year, according to a 2019 study by BLOMInvest, a Lebanese investment bank. About half that volume is shipped abroad, with the value of wine exports jumping from $13.8 million in 2015 to $20.3 million in 2018.

A cat sits atop a stone wall at Iris Domain, part of Lebanon’s 8.5 million-bottle-a-year wine industry. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

A cat sits atop a stone wall at Iris Domain, part of Lebanon’s 8.5 million-bottle-a-year wine industry. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post) Following the traditional French model of viticulture, Lebanon has dramatically expanded its crop without irrigation.

But the shifting rainy seasons are disrupting the crops, with May and June now seeing heavy precipitation and October and November uncommonly dry, Mohtar said. In 2019, when the rain came, it was so unusually intense that the soil couldn’t absorb much of it and the water was lost as runoff, he said.

Overall, the trend is toward less rainfall, with the country projected to see precipitation decline by 10 to 20 percent over the next 20 years, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Even if local growers wanted to break with tradition and introduce irrigation, water is relatively scarce here and the vineyards would have to compete with daily use by Lebanese for drinking, cooking and bathing.

To help the ground retain more moisture, Salibi has been adopting practices at his vineyard to mulch the soil. He planted fava beans between the vines, chopping down the plants before they matured and then plowing them under. In a few years, he hopes that will make the soil more sponge-like.

The changing temperatures are a separate challenge. An analysis from Berkeley Earth, comparing the average temperature in 2014-2018 with that in the late 1800s, shows that Lebanon has warmed by 2.1 degrees Celsius, or 3.8 degrees Fahrenheit. (If the average global temperature were to increase by that same amount, climate scientists say, Earth would experience irreversible, catastrophic damage.)

In response, winemakers expect that in a few years they will have to plant grapes like syrah that originated in warm-weather areas. Salibi is not a fan.

More generally, white wine — extremely popular in a country with more warm weather than cold — is under threat. “White wine is all about acidity,” Salibi said. “And acidity evaporates when it’s warm.”

But last year, Salibi couldn’t even count on the warm weather. He had to abruptly shutter his winery to weekend visitors after November’s abnormally cold weather settled in.

The vineyards at Chateau Khoury. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

The vineyards at Chateau Khoury. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post) Heat too early, cold too late

The inside of Chateau Khoury looks like the nearly bare belly of a steel beast: Massive aluminum tanks, labeled for different wines, are arranged in a U shape.

To the side, like something in a mad scientist’s lab, a table is heaped with bottles, containers and cylinders filled with various liquids and chemicals amid snaking tubes and assorted other equipment. Jean-Paul Khoury said this is where he experiments but, with a smirk, declined to elaborate.

In the cellar, down a set of large steps and carved into the mountain, are endless rows of dark bottles. Visitors are hugged by the warm smell of aniseed.

Khoury seems to love his work; it shows on his face. He is passionate about using every part of the fruit. After the grapes are squeezed, the husks, both skin and pulp, are distilled into aniseed-flavored arak. The remaining solid waste goes into compost.

Chateau Khoury owner Jean-Paul Khoury said he first noticed what he thought were disruptions caused by climate change in 2012. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

Chateau Khoury owner Jean-Paul Khoury said he first noticed what he thought were disruptions caused by climate change in 2012. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post) Khoury said he first noticed what he believed were disruptions caused by climate change in 2012. The early heat meant his harvest had to start three weeks earlier than usual.

When the heat wave hit last year, it caused all the grapes to mature at the same time, and they all had to be harvested immediately. Khoury said he and his team, including foreign employees and members of Bedouin tribes, worked tirelessly for 15 days to finish work usually done over two months.

Khoury said his last vat of cabernet sauvignon went into the distillery at a much higher alcohol level than the desired 12 percent. “It got too hot too fast.”

Boxes of wine at Chateau Khoury. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

A barrel of Chateau Khoury’s Symphonie wine. Government capital controls prevent the owner from buying oak barrels from France. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

LEFT: Boxes of wine at Chateau Khoury. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post) RIGHT: A barrel of Chateau Khoury’s Symphonie wine. Government capital controls prevent the owner from buying oak barrels from France. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

He’s also noticed the cold weather coming later. Winemakers need the first frost in order to begin pruning, usually in late October. Last year, it arrived in mid-November.

The difficulties arising from climate change have been exacerbated by Lebanon’s economic crisis. Khoury has had trouble paying his workers. Government-imposed capital controls mean he cannot make payments abroad, for instance for French oak barrels. His restaurant has been emptied by coronavirus restrictions. His bottle sales are down 70 percent.

And then there was the massive August explosion in Beirut’s port, which disrupted Khoury’s shipment of corks due to arrive four days later. The ship returned to France.

Last year was the worst season ever in Khoury’s eyes. “Even during the war in 2006 it was easier,” he said. “We don’t really know how to deal with everything that’s happening. And nothing really is done to help us work properly.”

Lebanon’s economic crisis has driven down bottle sales at Chateau Khoury by 70 percent. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post)

Lebanon’s economic crisis has driven down bottle sales at Chateau Khoury by 70 percent. (Myriam Boulos for The Washington Post) Photo editing by Olivier Laurent. Design by Emily Sabens.