February’s jobs report doesn’t let Congress off the hook for more stimulus

Falling covid infections, rising daily vaccinations and fewer business restrictions are all helping normal economic activity resume. This is worth celebrating! Still: The economic crisis and the suffering it has caused are nowhere close to over.

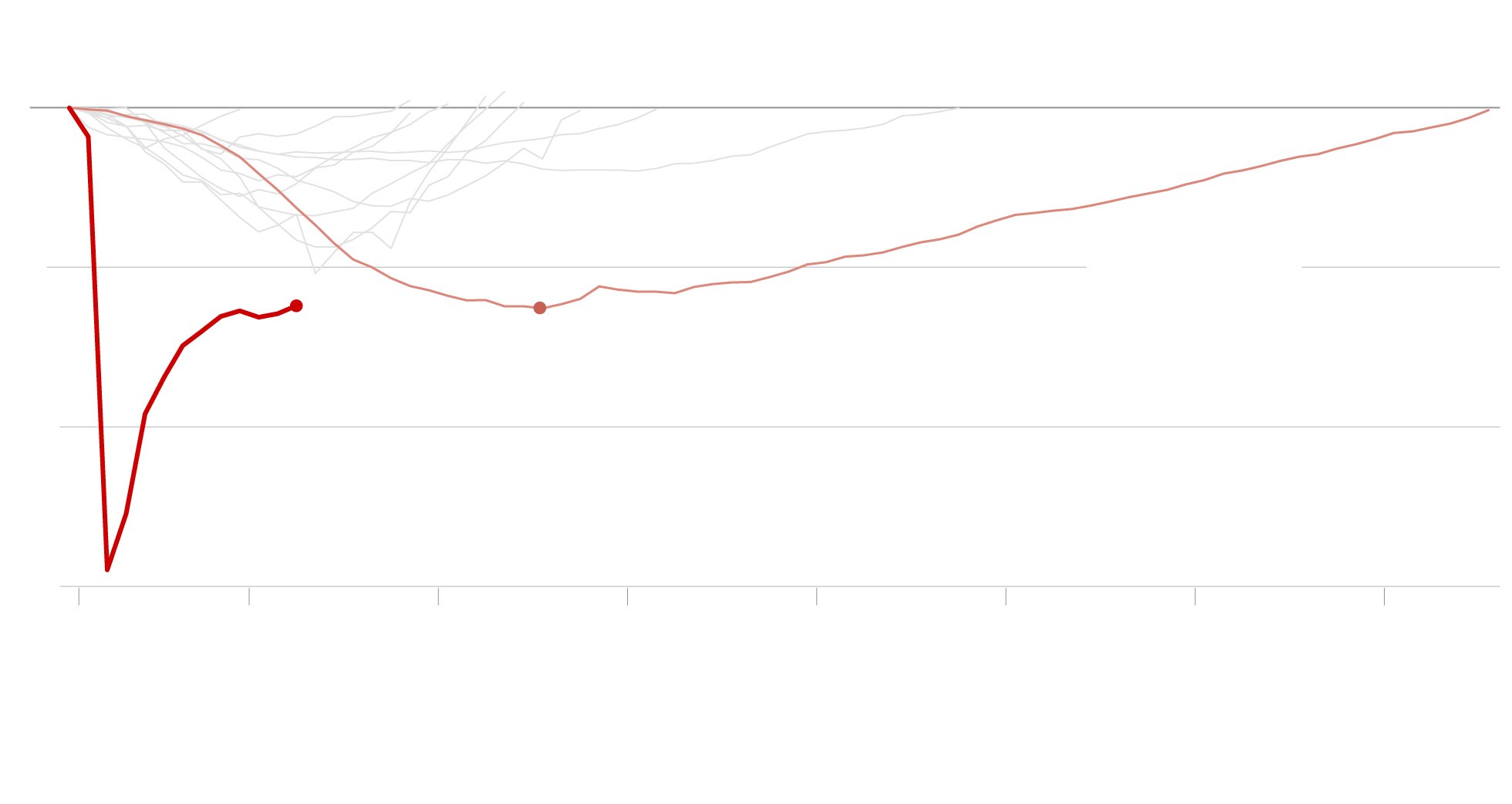

Even with February’s growth, the economy is still very deep in the hole. By more than 9 million jobs, to be precise. The jobs deficit — the share of jobs that are “missing” relative to when the recession began — is nearly as large today as it was at the worst point of the Great Recession. And the Great Recession was, uh, pretty awful.

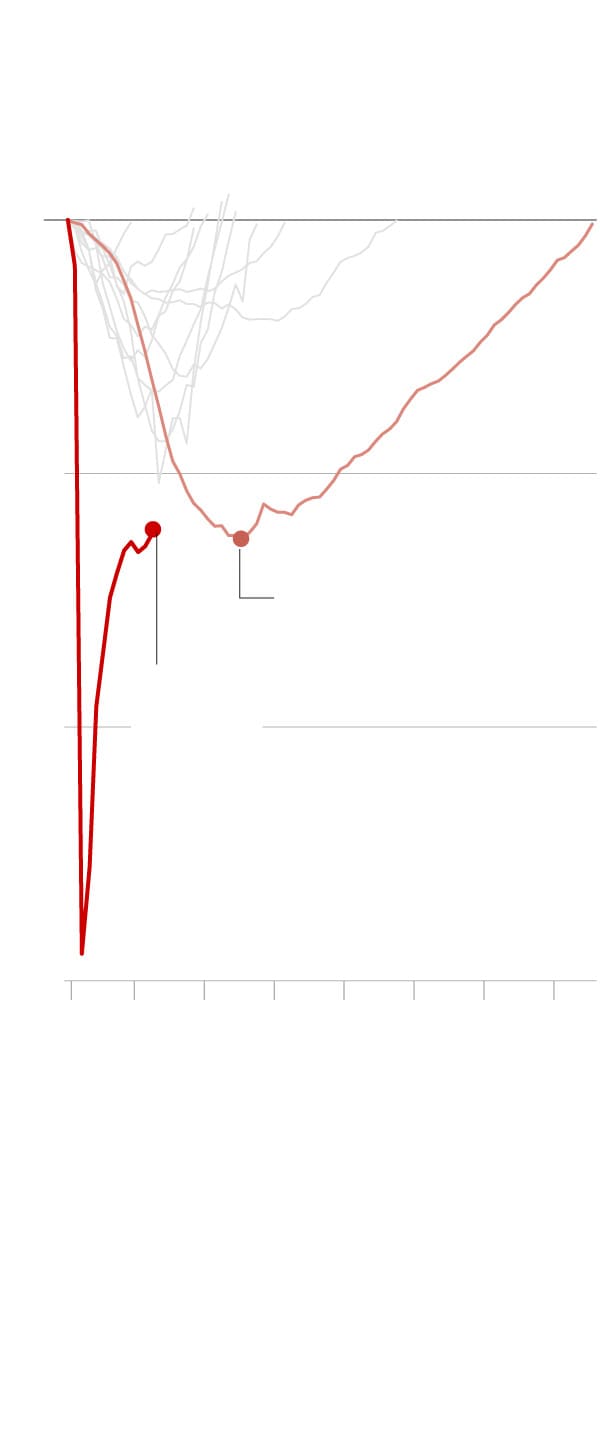

How this recession compares to previous ones

Percent change in employment since most recent peak.

Other post-

World War II

recessions

Great Recession

and subsequent

recovery

Worst point

after the

Great Recession

Where

we are

now

Months since the last employment peak

Note: Because employment is a lagging indicator, the dates for these payroll employment trends are not exactly synchronized with the National Bureau of Economic Research’s official business cycle dates.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics,

via Haver Analytics

THE WASHINGTON POST

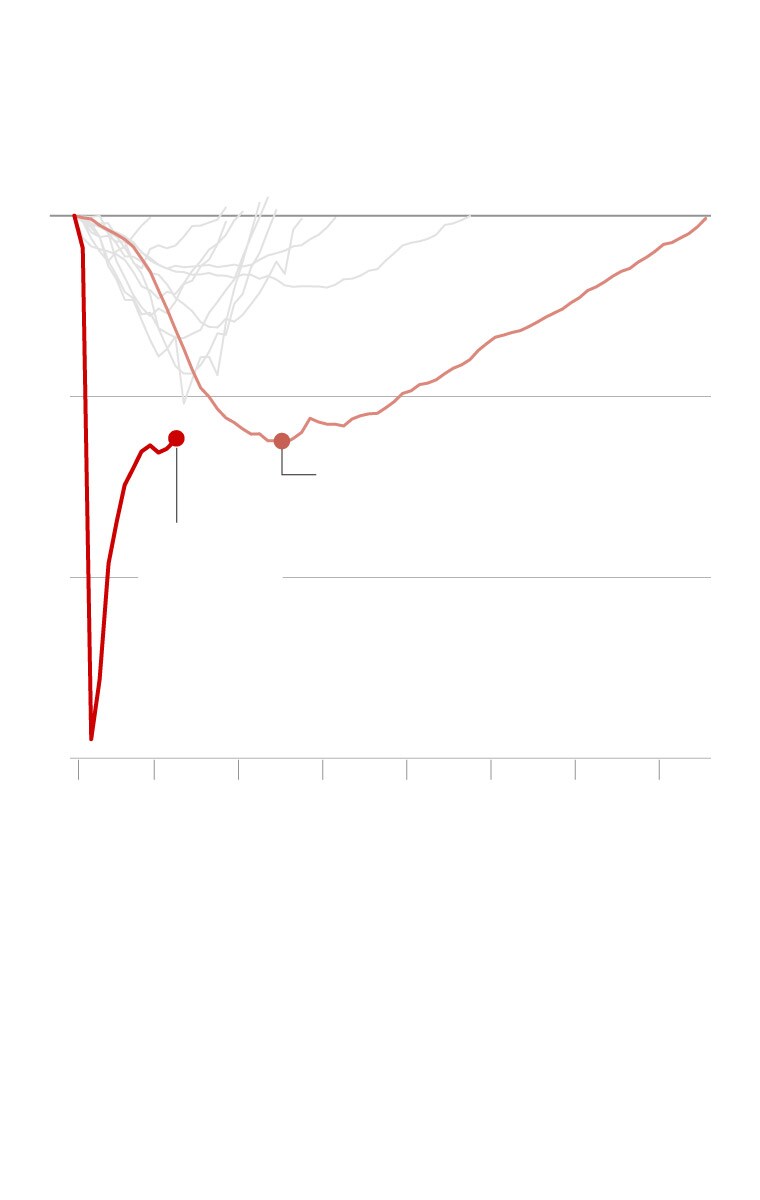

How this recession compares to previous ones

Percent change in employment since most recent peak.

Other post-

World War II

recessions

Great Recession

and subsequent

recovery

Worst point after

the Great Recession

Where

we are

now

Months since the last employment peak

Note: Because employment is a lagging indicator, the dates for these payroll employment trends are not exactly synchronized with the National Bureau of Economic Research’s official business cycle dates.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics

THE WASHINGTON POST

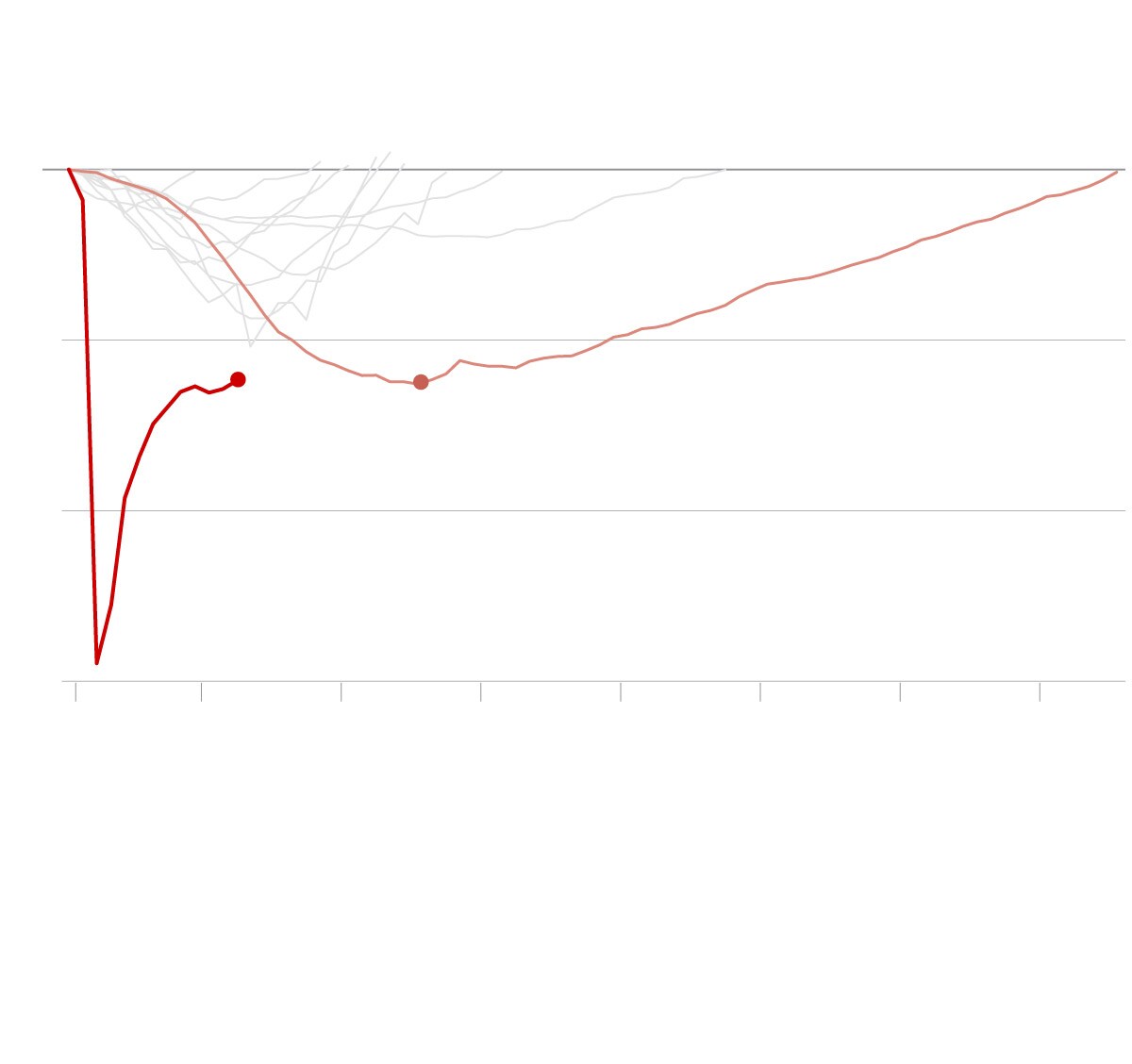

How this recession compares to previous ones

Percent change in employment since most recent peak.

Other post-

World War II

recessions

Great Recession

and subsequent

recovery

Where we

are now

Worst point after

the Great Recession

Months since the last employment peak

Note: Because employment is a lagging indicator, the dates for these payroll employment trends are not exactly synchronized with the National Bureau of Economic Research’s official business cycle dates.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics

THE WASHINGTON POST

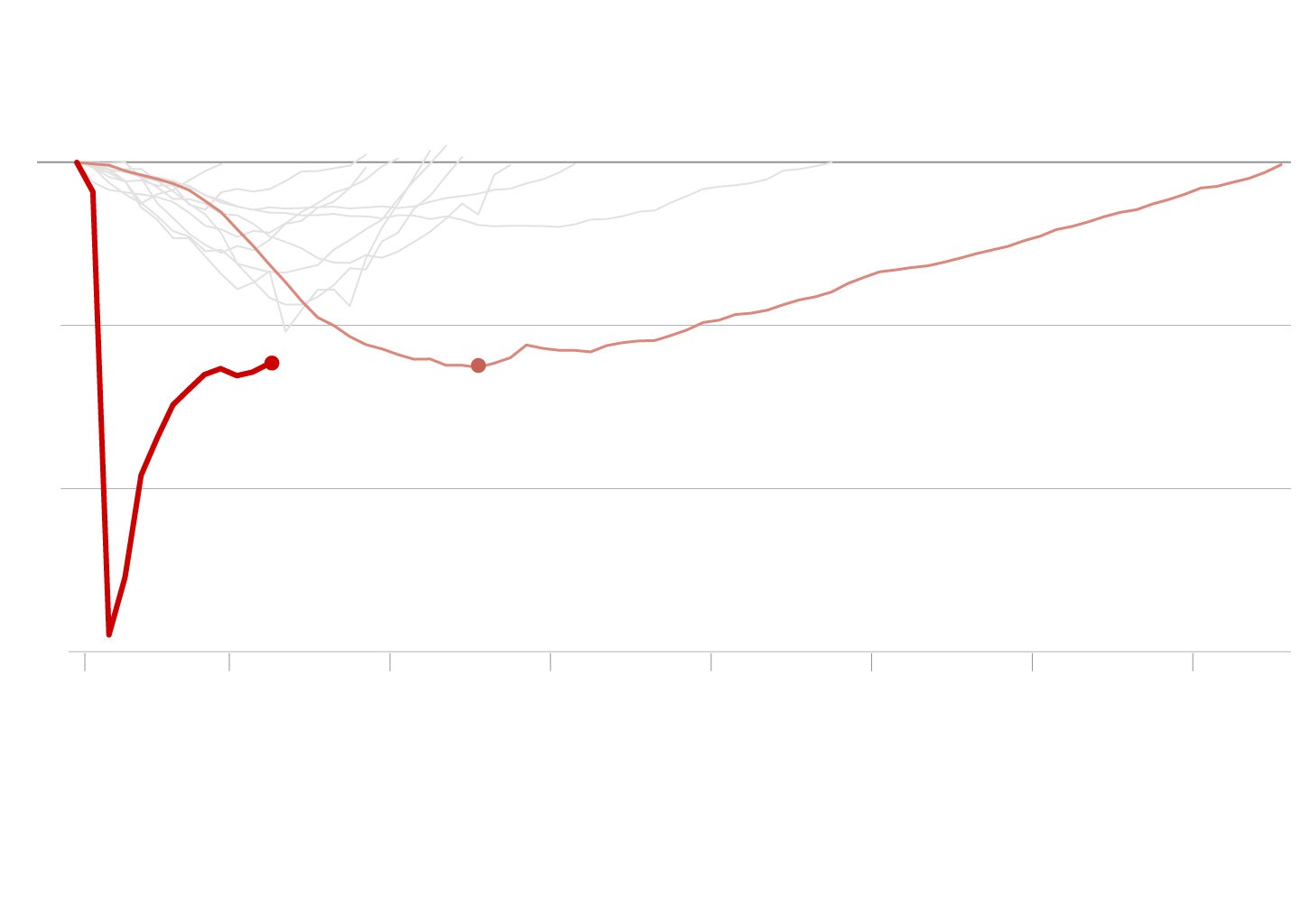

How this recession compares to previous ones

Percent change in employment since most recent peak.

Other post-

World War II

recessions

Great Recession

and subsequent

recovery

Where we

are now

Worst point after

the Great Recession

Months since the last employment peak

Note: Because employment is a lagging indicator, the dates for these payroll employment trends are not exactly synchronized with the National Bureau of Economic Research’s official business cycle dates.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics

THE WASHINGTON POST

How this recession compares to previous ones

Percent change in employment since most recent peak.

Other post-

World War II

recessions

Great Recession

and subsequent

recovery

Where we

are now

Worst point after

the Great Recession

Months since the last employment peak

Note: Because employment is a lagging indicator, the dates for these payroll employment trends are not exactly synchronized with the National Bureau of Economic Research’s official business cycle dates.

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics, via Haver Analytics

THE WASHINGTON POST

While February’s faster job growth represented progress, it’s still not good enough. If employment were to continue growing at February’s pace — so, 379,000 new jobs per month — it would take two more years to reach the level of jobs that existed pre-pandemic. And that still undershoots the goal, because the working-age population has continued growing. So we really want more jobs than existed when the pandemic began, rather than merely a recovery of jobs lost.

Even in the industry that showed the most improvement last month, this jobs hole remains huge. Employment in leisure and hospitality is about 20 percent below its level from a year ago.

Hopefully the pace of rehiring will accelerate as vaccinations pick up and the pandemic abates. But lingering weak spots in the economy suggest the ramp-up may be slower than workers need it to be.

State and local government education shed an additional 69,000 jobs last month. As schools reopen, those job losses might partly reverse, but absent more federal aid many state and local governments might have difficulty finding funds to rehire.

The number of long-term unemployed (those out of work for at least six months) barely budged in February and is up by 3 million from a year earlier. These people account for 41.5 percent of total unemployment; that’s not so far below the high from the Great Recession. Historically, the longer people are out of work, the harder it is for them to find new employment, whether due to skill deterioration, stigma, lost contacts or other factors.

Some of these workers may give up and simply never return to the workforce.

Already, the labor force (that is, the number of people either working or actively looking for work) shrank by about 4.2 million people over the past year. The research firm Capital Economics recently calculated that nearly 40 percent of this labor-force decline is due to “early” retirements — that is, older people who probably would have continued working for a few years if the job market had been stronger, but instead retired and now are unlikely to ever return to employment. Of course, younger dropouts who are not at or approaching retirement age may also become so discouraged that they never return to job-hunting.

Anything Congress can do to speed up the recovery and keep people attached to the labor force is critical to minimizing this kind of economic scarring. Likewise with keeping otherwise-viable businesses from permanently closing and with expediting children’s returns to in-person classes. (The latter is important not just for kids’ immediate mental health and social development but also their future earning power.)

The Senate is debating another round of fiscal relief. The most urgent deadline for this $1.9 trillion package involves preventing the expiration of federal unemployment programs, which are set to lapse in about a week. But there’s lots of other necessary stuff in the legislation too — including support for businesses, child care, rental assistance and so on.

Is the bill perfect? Definitely not. If I had my druthers, I’d probably extend funding for more weeks of unemployment benefits and instructional time for kids — and allocate less for, say, pensions. I’d probably save or reallocate some money for long-term priorities such as infrastructure or investments in children.

But on the whole, another round of federal aid is still economically necessary. Moreover it’s tremendously popular. It’s weird that Republicans refuse to support it. This latest jobs report, as encouraging as it is, should not reduce pressure to get this bill over the finish line.

Read more: