The reason there are ‘superstars’ today is because of Elgin Baylor

Switching the ball from hand to hand while in midair. Gliding from one side of the basket to another. Turning his back to the rim and flipping a shot over his head. Erving studied all of those moves, mimicked them, perfected them, until he was able to turn ABA and NBA arenas into his canvas, beautifully defying gravity with his own eye-popping circus shots. Those plays deified Erving in the eyes of future generations who were fortunate enough to watch live or catch one of his countless highlights. But Erving had an instructor in Baylor.

“Elgin should be the model,” Erving said in an interview Monday, also mentioning the influence of Connie Hawkins. “He should be the poster man.”

Before he became Dr. J, Erving was a Baylor fan. So much so that he describes his first encounter with Baylor — many years after he was mesmerized by what he saw on the screen — as “mouthdropping.”

“He was definitely an innovator and ahead of his time,” Erving said. “The driving and the versatility and the dexterity. That was an art form. He’s one of the guys, if you want to ask the question about playing in today’s game, he would fit right in with today’s game. No question about it.”

Baylor died Monday at age 86, and he leaves as a pioneering, influential figure who never quite got the flowers he was entitled to while alive.

The Lakers are regarded today as one of the greatest franchises in professional sports, let alone the NBA, but Baylor, the No. 1 pick of the 1958 draft, rescued them when their failings in Minnesota forced then-owner Bob Short to move the team and become the league’s first organization on the west coast. Athlete protests are now commonplace, but Baylor is still revered as the first to refuse playing a game because of racial discrimination during the civil rights movement. And the line that connects LeBron James, Kobe Bryant, Michael Jordan and Erving begins with Baylor, the game’s, no world’s, first superstar. No, seriously, the term “superstar” was coined for Baylor.

Bijan C. Bayne, author of Baylor’s biography, “Elgin Baylor: The Man Who Changed Basketball,” shared the story of how legendary sportswriter Frank Deford wrote a letter to the editor of New York Magazine after it published a story touting pop artist Andy Warhol as the originator of the word, “superstar.” Deford, then a famed Sports Illustrated scribe, explained that the word, which had yet to make its way in any dictionary, had never been used until it was made in reference to Baylor.

“He actually added a very important word to the lexicon because of his brilliance,” Bayne said of Baylor.

Baylor never led the Lakers to an NBA title because Bill Russell and the Boston Celtics were always there to ruin his trips to the Finals, and he never claimed any individual honors for scoring or rebounding because Wilt Chamberlain wasn’t relinquishing those titles.

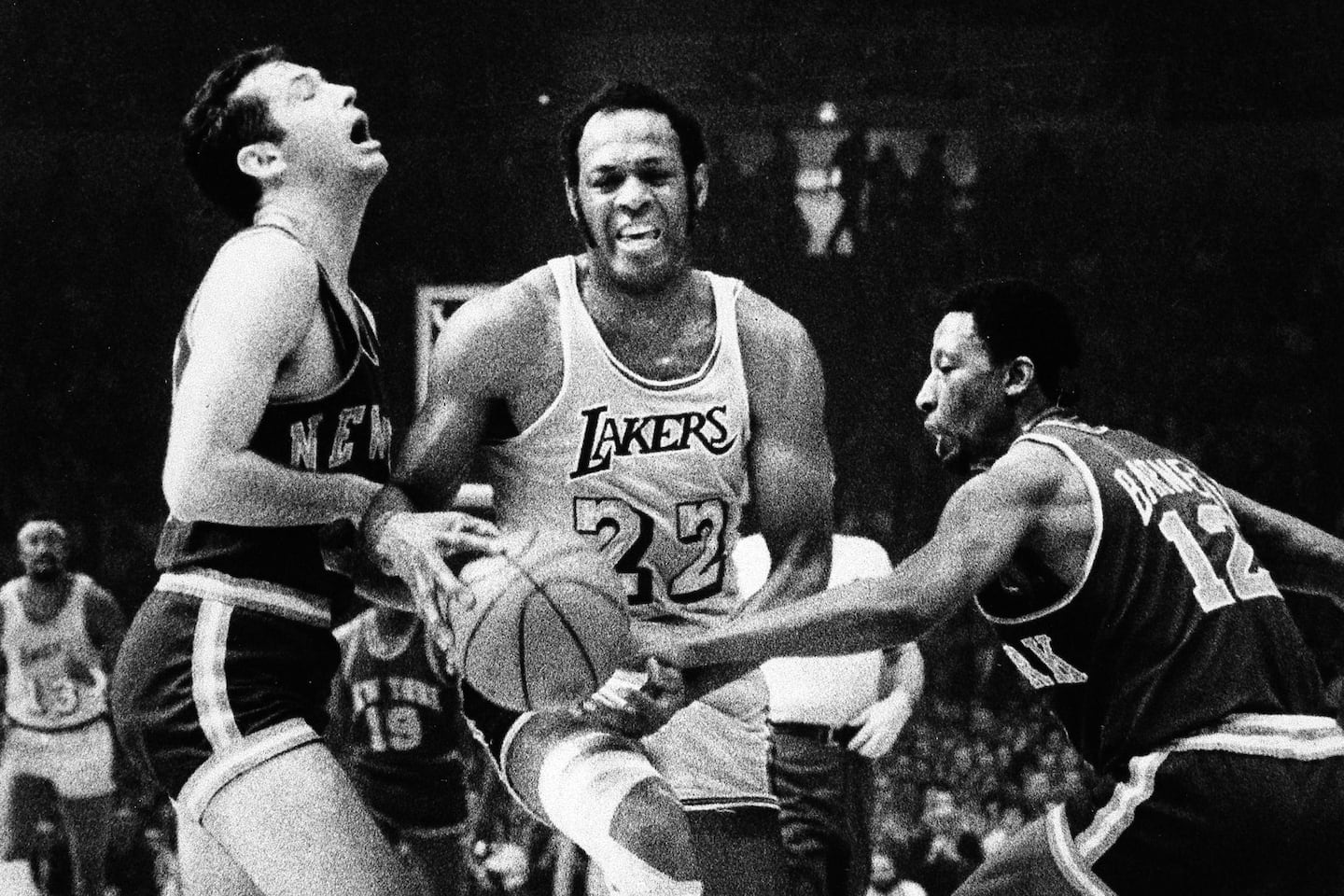

The numbers Baylor produced are still strong enough to elucidate his greatness — the first player to score more than 70 points in a game, the only player to surpass 60 points in a Finals game, the third-highest scoring average in NBA history, the only player shorter than 6-foot-6 to rank in the top 10 all-time for rebounds per game. Hangtime? That started with Baylor. The dribble move known as the “Euro step” where you take one step toward one direction, then take another across your body to hold off a defender; Baylor was doing that six decades ago.

Butch McAdams, the longtime Maret School boys’ basketball coach who later became a sports radio personality, said Baylor had a nervous twitch in which he’d nod his head, uncontrollably, while dribbling.

“It’s almost like when Michael Jordan would stick his tongue out,” McAdams said. “Whoever was guarding him, you knew you were in for it. He was getting ready to cook you.”

But he contributed more than some stunning plays that were captured on the grainiest of black-and-white film. Baylor stood up for himself, and those who either lacked the courage or platform to speak out against injustice. He grew up in segregated Washington and didn’t start playing organized basketball until he was about 14 because he was denied access to venues where he could play.

During Baylor’s rookie season, the Lakers were in Charleston, W.Va., playing a homecoming game for native “Hot Rod” Hundley against the Cincinnati Royals. Baylor, Ed Fleming and Boo Ellis arrived at the Kanawha Hotel and the front desk clerk informed them that the “colored boys” would have to stay somewhere else. Hungry, Baylor decided to get something to eat while the Lakers tried to resolve the problem.

But when he and his Black teammates showed up at a nearby restaurant, they were again denied service. Baylor, in turn, decided to deny Charleston of his talents and sat out in protest. Hundley, who often roomed with Baylor, urged Baylor to play in a game that meant a lot to him. Baylor had too much pride.

“Rod, I’m a human being,” he told him. “I’m not an animal put in a cage and let out for show. They won’t treat me like an animal.” Neither the Lakers nor the NBA took action against Baylor.

The NBA players threatened to strike during the 1964 All-Star Game, the first to ever be televised, if the owners didn’t recognize their union. As players made their demands known, passing notes through a police officer standing outside, Short threatened through a barricaded door that Baylor and his teammate Jerry West would be fired if they were involved in the protest.

“Baylor shouted loud enough for him to hear, for Bob Short to go have sexual relations with himself,” Bayne said.

Baylor could speak bluntly because he knew his worth. He was the player who single-handedly took a team from 53 losses to the NBA Finals in one year, the attraction for celebrities such as Doris Day, Bing Crosby, James Garner and Danny Thomas. The Lakers’ move to Los Angeles in 1960 barely registered when it was announced, but the team was moving into a new arena, the fabulous Forum, within seven years because owner Jack Kent Cooke needed a venue that could accommodate supporters.

“The whole reason Bob Short moved them to Hollywood was this guy that was too big of a showcase for Minneapolis,” Bayne said.

In his hometown of Washington, Baylor is exalted by those who saw him play in person. The late John Thompson Jr. dedicated a chapter of his autobiography, “I Came As A Shadow,” to Baylor, using the nickname Baylor had received as a kid, “The Rabbit.” Thompson wrote about how much he idolized and admired Baylor: “When people talk about the best ever to come out of Washington, you need to put Elgin at number one, skip over two, three, four and five, then count the rest of the guys from there, including Kevin Durant.”

Baylor’s lone ring came in 1972, the season in which he retired after nine games. And since his best moments occurred while the NBA struggled to find relevance on the sports landscape, and when big men ruled the league, Baylor never got the recognition his career deserved. His largely unsuccessful stint as general manager of the Los Angeles Clippers — which can be blamed largely on bumbling, bigoted and ousted owner Donald Sterling — is what he’s most remembered for, among younger fans of the game.

“Coach Thompson had a saying, and it goes like this: ‘Basketball is like church. Many attend, but few understand,’” McAdams said.

McAdams lists Baylor on his D.C. Mount Rushmore, alongside Durant, Adrian Dantley and Dave Bing, but added, “It starts with Elgin Baylor, because Elgin Baylor was doing things before the average person could dream of it. If you’re sitting around, in a sports bar, a party or wherever and you’re talking D.C. basketball and people want to talk about the GOATs … if they don’t start with Elgin Baylor, end the conversation.”

Erving said Baylor is on his all-time starting five, along with West, Chamberlain, Russell and Oscar Robertson. “Which I decided when I was 15 years old and haven’t changed,” Erving said with a laugh. “Sometimes when you make decisions at 15 and stick with them while you’re 71, they call you a little delusional.”

But when it comes to Erving and Baylor, that eternal fandom can essentially be called an appreciation.