America forgot how to make proper pie. Can we remember before it’s too late?

I grew up in a home in which pie was spoken fluently. As a child, I assumed that pie appeared on everyone’s table, as it did year-round on mine. Looking back, I seem not so much to have traveled the circle of the sun as it inched through the seasons but around the rim of a pie tin: Lemon meringue to sour cherry, sour cherry to purple raspberry, purple raspberry to peach, then onward to apple and, finally, to holiday pumpkin and pecan.

It was only when I left home that I realized how unusual it was to have a mother and grandmother who tossed off perfect pies the way some people drop witty epigrams — and how borderline miraculous their pie crusts were.

Megan McArdle is a Washington Post columnist and the author of “The Up Side of Down: Why Failing Well Is the Key to Success.”

Photo by Tom McCorkle for The Washington Post; food styling by Lisa Cherkasky for The Washington Post

For a lot of people, pie is all about the filling; the crust is an afterthought. Without the crust, though, you are eating a mousse, a custard or a compote — delicious all, but distinctly not pie. And if you are going to encase those excellent things in a flaccid flap of flavorless pastry, why not skip the extra calories and make only the good part?

So a pie worthy of the name must have a good crust — not just a vehicle for filling but a delight in itself. It marries tenderness with flakiness. It’s delicate, yet strong enough to keep the filling where it belongs. It’s nothing like the tough, desiccated things that most people mean when they say “pie crust.”

That’s not exactly their fault, because probably most of those crusts are store-bought. In 2019, more than 50 million Americans used frozen pie crusts, and more than 40 million used the refrigerated kind. Even though store-bought crust is terrible.

Yet commercial bakeries don’t do much better. When I covered Democratic primaries early last year, I tried to visit the most famous pie shops in each state. After more than a dozen stops, I found exactly two pies that I’d willingly take home to meet my parents. (They were the cherry crumb and brown butter pecan at Petsi Pies in Somerville, Mass. Next time you’re in Boston, do yourself a favor.) Most of the others had crusts that were too flabby, too tough or too overcooked to be worth eating.

How can they get away with this?, I wondered. Thinking about this well before covid-19 set off a nationwide baking renaissance, I realized that Americans, who mostly stopped making their own pie crusts long ago, have nothing better with which to compare them.

That’s one reason why, at age 48, I decided to apply myself to piemaking. For the first time in my adult life, I’m not trying to push my culinary boundaries outward, mastering a novel ingredient or dish. Instead, I am beating backward and inward, toward something I’ve always known and can’t afford to lose.

[Read the author’s family recipe for mock purple raspberry pie]

So this isn’t just an essay about pie. It is a polemic. I want to convince you that American pie is special, because it is. American pie is great, in part, because of its rich, unlikely history. But American pie is also in dire straits, because American cooks have mostly forgotten how to make the most important part.

Which means that we are at risk of losing not just a dessert, but a little piece of who we are as a country.

The Great Pastry Schism

My mother’s family has probably been making pies since shortly after it arrived here in the 1620s. By then, Britain’s pie tradition stretched back centuries to the cooks who encased hunks of meat in a thick armor of floury dough known as a “coffin.” For years, American culinary traditions were largely theirs; the first American cookbook, the 1796 “American Cookery” by Amelia Simmons, clearly resembles its English counterparts.

Shortly after we gained independence from Britain, our piemaking traditions also began to diverge. If you have ever watched “The Great British Baking Show,” you know that to a Brit, a pie is something often made with meat, such as pork or steak or, more recently, curried chicken. To modern Americans, pie is almost exclusively a sweet dessert. This trend toward sweetness begins to emerge in U.S. cookbooks as early as the 1830s.

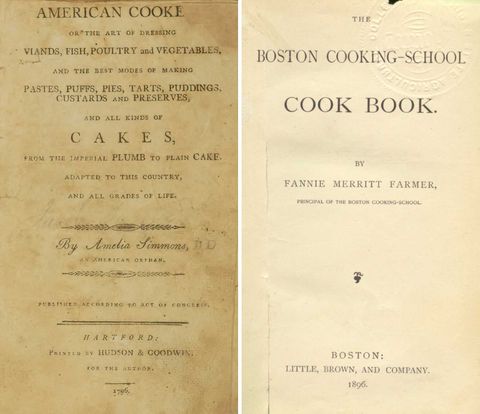

“American Cookery” by Amelia Simmons, left, and Fannie Farmer’s “Boston Cooking-School Cook Book.” (Michigan State University Library)

“American Cookery” by Amelia Simmons, left, and Fannie Farmer’s “Boston Cooking-School Cook Book.” (Michigan State University Library) “The pie is an English institution,” Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote in her 1869 novel “Oldtown Folks,” “which, planted on American soil, forthwith ran rampant and burst forth into an untold variety of genera and species. Not merely the old mince pie, but a thousand strictly American seedlings from that main stock, evinced the power of American housewives to adapt old institutions to new uses. Pumpkin pies, cranberry pies, huckleberry pies, cherry pies, green-currant pies, peach, pear, and plum pies, custard pies, apple pies, Marlborough-pudding pies, — pies with top crusts, and pies without, — pies adorned with all sorts of fanciful flutings and architectural strips laid across and around, and otherwise varied, attested the boundless fertility of the feminine mind, when once let loose in a given direction.”

“American Cookery” includes a number of savory pie recipes, but only three for fruit pies. By 1896, Fannie Farmer’s famous cookbook almost exactly reversed this: There is an entire chapter on sweet pies, but only two recipes for meat pies — beefsteak and chicken.

It seems natural that America, with its proximity to Caribbean sugar plantations, would end up making more sweet things; even now, we like to slather meat with sweet ketchups, sugary barbecue sauces or mustard dips rich with honey. But that doesn’t explain why we started abandoning meat pies.

In her 2009 history of pie, Janet Clarkson suggests this reflects a shortage of wheat, which remained relatively scarce in the United States until settlers moved to the Great Plains. Housewives might have saved their flour to make sweets, which tend to be eaten in smaller quantities than the main course.

Too, as settlers moved west, Eastern orchards supplied dried apples for the journey. These apples were, Clarkson says, inevitably used to make pies, which perhaps firmed up the association of “pie” with “sweet.”

TOP: BOTTOM LEFT: BOTTOM RIGHT:

Apple, sour cherry and pumpkin pies made from author Megan McArdle’s family recipes. (Photos by Tom McCorkle for The Washington Post; food styling by Lisa Cherkasky for The Washington Post)

It’s also possible that the meat pie disappeared because early American health reformers fixated on it, if for reasons that remain obscure. The author of one mid-19th-century cookbook practically berated her readers for such an unwholesome interest: “It would really be a great improvement in the matter of health . . . if people would eat their delicious summer fruit with good light bread, instead of working up the flour with water and butter into a compound that almost defies the digestive powers . . . And yet women will make pies; and mothers will give them to their young children.” The author also wrote that meat pies “should never be made.”

This seems practically sane compared with Mrs. E.E. Kellogg, wife of John Harvey Kellogg, a health fanatic who is better known to modern Americans as the father of breakfast cereal. In the December 1883 edition of their newsletter, Mrs. E.E. printed the claim that pie causes . . . alcoholism.

Space constrains me from laying out the argument in its full, glorious delirium, but it is roughly summed up in the section where the author chides pie-proffering mothers for driving their children “from improper food to dyspepsia, from dyspepsia to bad medicine, and from thence to strong drink.”

Americans back then were no less susceptible than we are to health fads. But perhaps, like us, they found it hardest to give up their favorite desserts, so maybe savory pie died under the onslaught of the Kelloggs and their fellow travelers, while sweet pie survived as a guilty pleasure.

Whatever the reasons, by the end of the 19th century, savory pies had almost vanished from the American lexicon. Which is when, I’d argue, American pie really hit its stride.

The Golden Age of Pie

In 1905, the Supreme Court pondered one of the era’s vital questions: Could a state limit a baker’s working hours?

Henry Weismann, a lawyer for bakery owner Joseph Lochner in Lochner v. New York, appealed to reason and practicality. Then he grabbed the heartstrings and yanked:

“Then there is the American housewife. Here is the real artist in biscuits, cake, and bread, not to mention the American pie. The housewife cannot [limit] her daily and weekly hours of labor. She must toil on, sometimes far into the night, to satisfy the wants of her growing family. It seems never to have occurred to these ungallant legislators to include within the purview of the statute these most important of all artists in this most indispensable of trades.”

Note that he invoked “the American pie.” Stowe’s consciousness of pie as something peculiar to us had clearly taken hold — broadly.

“The pie is an English institution which, planted on American soil, forthwith ran rampant and burst forth into an untold variety of genera and species.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe

Until the latter half of the 19th century, pie had a definite association with Stowe’s New England. People everywhere ate it, especially on Thanksgiving, but New Englanders were reputed to be mad for the stuff, eating pie at every meal.

But sometime after the Civil War, pie began to break out of its regional boundaries.

“New England once was called the pie belt,” wrote an editorialist in the Baker’s Helper in 1921. “Today the United States is the pie belt.”

The “pie chest” was common — a cupboard with perforated tin door panels to let pies cool in safety. Which suggests how many pies American cooks were making.

Americans who ventured far from their pie chests wrote from abroad, lamenting their inability to procure a decent pie. A correspondent to one Mormon youth magazine reportedly declared pie to be “the bulwark of our American civilization . . . the one thing that differentiates the progressiveness and assertiveness of the New World from the bourbonism and effeteness of the Old.”

At home, Americans wrote newspaper editorials and speeches about pie. One dinner speaker noted that “among the attainments of our American women, the making of pie is one that has the most far-reaching influence from Maine to California.” This was not some meeting of professional bakers; it was offered at the San Francisco conference of the American Library Association.

This is approximately when the American pie assumed its final, highest form.

Having mastered the crust, American cooks then started, like jazz musicians, to play variations. As novel ingredients such as bananas became more widely available, and refrigeration more common, cooks added the iconic cream pies to their repertoire; with the advent of cheap and reliable gelatin, they began making airy chiffon pies. Not all their inventions were a good idea — you wouldn’t believe, or eat, what some of them got up to with marshmallows. But enough were sound that I feel confident labeling the first decades of the 20th century as American pie’s golden age.

But this was also the moment from which you can mark its decline. And for that, we might have cake to blame.

The Tech Revolution

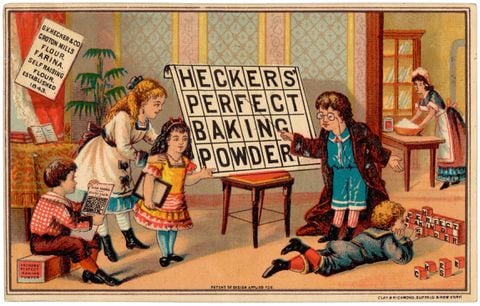

A late 19th-century advertising card for Heckers baking powder.

A late 19th-century advertising card for Heckers baking powder. Before chemical leavening became common with the invention of commercial baking powders in the mid-19th century, cooks had two main ways ways to make a light cake rise. They could add enough sugar to a bread dough to form a “cake” that we would call a very sweet bread, such as a babka or a panettone. Or they could beat air into their batter with great force so that tiny pockets were trapped within the network of fats and proteins. During baking, the air would expand as it heated, making the cake rise.

Baking powder — a mixture of sodium bicarbonate and acid that, when wet, emits carbon dioxide gas — made light cake easy and common. Next came the (hand-turned) rotary eggbeater — and, suddenly, meringues that had previously taken frenzied beating with a fork or wire whisk could be achieved in minutes of easy labor.

Soon, these technologies were joined by the real magic dust of its era: cheap, reliable powdered gelatin. The Jell-O mold is a joke to foodies today, but before the invention of granulated gelatin, a molded dessert or salad meant some expensive, daunting and laborious process, such as clarifying and straining calf’s foot jelly. At the turn of the 20th century, first Knox, and then Jell-O successfully marketed products to American housewives that merely required boiling water and whatever you wanted to add — as though you could instantly replicate dinner at Per Se, for a few cents a packet or about $2.50 a box.

The miracles piled atop one another. Coal and wood-fired stoves gave way to gas or electric ovens, with thermostats — a boon to baking. Iceboxes gave way to refrigerators, making it easier to set a mousse or a gelatin mold. Electric mixers cut the time and effort needed to whip up a cake or a batch of cookies. Cake mixes allowed even inept cooks to produce something edible, if not extraordinary.

Many of these inventions also assisted pies, of course. A little baking powder could help your less-than-flaky crust. Mixers could speed up the process of cutting fat into flour.

But while technological advances were making desserts easier, they weren’t getting easier at the same rate.

Cake had once taken more time and labor than pie, which might be why Americans liked to say something simple was “easy as pie.” Today, with sufficient instructions and the right equipment, even an unskilled cook can turn out a decent mousse, custard or layer cake in a few hours — most of which is spent waiting for the thing to bake or set. But pie still takes all day, a good deal of mess and a bit of muscle. No wonder we stopped making so much of it.

How to do it right

“Cooking is art; baking is chemistry,” they say, and by and large, that’s true. Cook an entree with a relatively free hand, and you might produce something pretty good. But you can’t just toss some dry ingredients together with fat and a little liquid and hope to produce an airy cake or a delightfully crisp cookie. You have to get the ingredients exactly right: Weigh and sift and fill your liquid measure at eye level, making sure not to add even a drop too much; preheat your oven and butter and flour your pans; add the ingredients in order. If you do all that, you will likely produce something tasty.

But pie crust is not quite art and not quite chemistry; it is a bit of magic, too.

To make pie crust as my grandmother did, you take cold fat and cut it into flour, until the pieces are roughly the size of a small pebble. Then add water — cold water so the shortening won’t melt until it hits the oven — and work it in until the dough is just wet enough to hold itself together. Finally, you press it together just enough to create a weak network of the protein called gluten before putting the dough in the refrigerator to chill for several hours.

That network forms the scaffolding within which the chunks of fat will melt when baked, creating the characteristic flakes that distinguish pastry from a flour tortilla. If you add too much water, or work it even a little too much, the gluten will get overexcited, and you will end up with something chewy and listless, rather than flaky and tender.

(Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post)

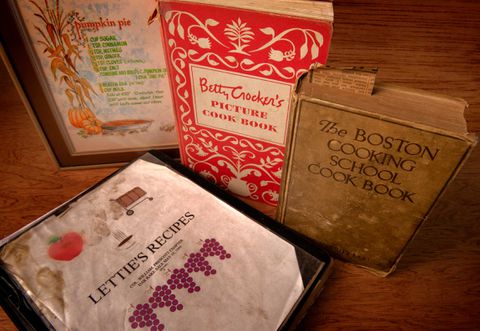

(Bill O’Leary/The Washington Post) These are the cooking foundations of my family: Grandmother McArdle’s Boston Cooking School cookbook, the Betty Crocker cookbook that my family still does most of its baking from, the famous pumpkin pie recipe and a collection of family recipes that my Great-Aunt Helen made into a large-type book for my Grandmother Farrell when she started to go blind from macular degeneration.

Unlike most traditional recipes, you can’t know in advance exactly how much water you will need. That depends on your flour, the ambient humidity and, I believe, whether the pie gods are feeling vengeful. So you must add water a little bit at a time until it looks and feels right.

Those last steps cannot be subcontracted out to children, as my mother once assigned me to measure the flour and my sister to work the mixer for her cakes. Pie crusts require the judgment of an experienced pastry-maker, because they can’t be precisely timed or measured. It’s all in the cook’s hands — literally. They work by feel at least as much as by eye.

There is a moment when the magic happens, or it doesn’t, and seizing it takes practice. If you use a food processor, as most people do these days, you can’t explain the moment to take your finger off the button; you just know. And if you assemble the loose crust with a technique known as fraisage — as my mother does — in which small handfuls of the dough are pushed along your work surface to make a flakier, more layered crust, you cannot show someone else the exact amount of pressure that creates long, fine layers with streaks of butter between them, without waking up the gluten.

In recent years, food hackers have invented pie crusts that work more like cake recipes — using exact amounts to produce a dough that comes together much more easily. But you still have to roll out the crust, which requires some skill, no matter how easy YouTube videos make it look. The crust cracks, and those cracks must be closed immediately, lest they splinter into a 20-armed starfish. You must apply even pressure to achieve the same thickness all around. Inexperienced rollers are more likely to end up with something paper-thin on one side, inch-thick on the other. It is also apt to be more of an oval, or a rhomboid, than the circle of your pan.

If you are making a two-crust pie, you need to run this gantlet twice. We will not even speak of lattices and other decorative flourishes.

Moreover, once you take your well-chilled dough out of the refrigerator, the butter lumps begin to soften, so all these problems must be solved within minutes, because if the butter gets too soft, the pastry will tear or lose its flakiness. But don’t roll too hard or too much, because if you overwork the gluten, the pastry will retaliate by toughening up.

Finally, there’s assembly: Roll the crust onto your rolling pin and drape it over the pan, then press it in firmly but lightly, without tearing.

How do you know when you have done it right? Only by practice, unless of course you are like my paternal grandmother, Catherine, whom I never knew but who reportedly whipped out crusts so thin and fine you could see your hands through it.

Can we save our pie?

Mock Purple Raspberry Pie, made from author Megan McArdle’s family recipe. (Tom McCorkle for The Washington Post; food styling by Lisa Cherkasky for The Washington Post)

Mock Purple Raspberry Pie, made from author Megan McArdle’s family recipe. (Tom McCorkle for The Washington Post; food styling by Lisa Cherkasky for The Washington Post) All this helps to explain why no one makes a good pie on the first try. And why, year after year at Thanksgiving, so many families decide to buy the pie crust — or the whole pie. Or perhaps we’ll just buy a nice pumpkin cheesecake.

Every time families make those choices, they break a chain that had stretched across centuries, from mother to daughter and oven to oven. And reknitting the links is exceedingly difficult, because the children and grandchildren of those who incrementally abandoned pie don’t even know what to aim for.

Novice piemakers, no matter how careful, are apt to make something tough, and not particularly appetizing — probably much like all the other pie crusts they have ever eaten. If they don’t know what they’re missing, that’s where they’re likely to stop.

Which is why I fear the American pie is going to die from neglect. As food culture gets better and better, and many found themselves stuck at home during the pandemic, Americans adopted lost arts such as cheesemaking and beer brewing. But even if pandemic lockdowns created a nation of newly minted bakers, can they bring back something they don’t even know?

Well, I am by nature an optimist and, thanks to the advances of food hackers, I believe we can have our pie back, maybe even better than it ever was. With a little equipment and some patience, even people innocent of good pie crust can produce something delectable. All they have to do is remember how to want it.

(Courtesy of Megan McArdle)

(Courtesy of Megan McArdle) My Grandmother Farrell, Aunt Annie, Grandpa Farrell and a roughly 6-year-old me at the dining table, eating purple raspberry pie. Those are the Christmas decorations, so the pie would have been made from frozen berries, taken fresh from my grandfather’s garden in summertime. That pie is my favorite food in the entire world.

Read more:

Read Megan McArdle’s family recipe for mock purple raspberry pie

Our best July Fourth recipes for grilled meats, seasonal sides and make-ahead desserts

Megan McArdle: Why Betty Crocker’s 1950s cookbook resonates with me now

Sudeep Agarwala: Think you’re out of baker’s yeast? Think again.

Tamal Ray: I spend my day working in the hospital. Then I come home and bake.

James Hohmann: My beef with Epicurious