Deep in rural France, in a medieval courtyard in Figeac, I almost tripped on the Rosetta Stone. Unlike the surrounding sandstone houses and half-timbered facades, the enormous slab stands out in black granite, inscribed with three different scripts, including Egyptian hieroglyphics. This isn’t just a reproduction of the famous stone that unlocked the mysteries of ancient Egypt. This is a monumental work by American conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth that pays homage to the town’s native son and hieroglyphics decipherer, Jean-François Champollion.

France fetes the man who solved the Rosetta Stone mystery

Two hundred years after this earth-shattering discovery, I went on a quest to learn about the man who cracked the code. From modest origins, Champollion would go on to determine the chronology of Egyptian pharaohs, launch the Egyptian antiquities department at the Louvre and help found the field of Egyptology — all before an untimely death at age 41. The decipherment is an extraordinary story of passion and perseverance, particularly considering he never even saw the real Rosetta Stone. France is throwing a party this year to celebrate.

Taking place all over the country, the bicentennial is a veritable Egyptomania fest of exhibits and events. Here’s a sample: The French National Library is hosting an ambitious show, three years in the making, featuring Champollion’s unpublished documents alongside spectacular artifacts; the Arab World Institute in Paris has opened a virtual-reality experience called “The Horizon of Khufu,” taking visitors “inside” the Great Pyramid; the Mucem in Marseille is staging “Pharaoh Superstars,” equating the fickle nature of the pharaohs’ posthumous fame to present-day pop culture; and the Louvre’s northern satellite in Lens will stage an autumn exhibit on hieroglyphics and Champollion’s story, accompanied by an “Egyptobus,” or mobile museum, touring the Pas-de-Calais region.

But it’s Champollion’s birthplace that’s going all out, with a six-month program called “Eurêka!” Running through October, the cultural extravaganza includes concerts, movie screenings, theatrical shows, museum exhibits and seminars with leading Egyptologists. Restaurants are offering themed dishes, combining French and Egyptian flavors. There’s even an initiative whereby local Figeacois pay homage to Egypt in their shop windows. But perhaps the coolest part of all is the sound and light show that will be projected on the historical facades of the Place Champollion on Thursday and Saturday nights in July and August.

“Champollion was a child of the Enlightenment who illuminated the era,” says Hélène Lacipière, a city councilor and vice president in charge of culture and patrimony for Grand Figeac. “We designed ‘Eurêka!’ to showcase how this territory [an aeronautics hub] is one of invention and discovery. … We are simultaneously a land of traditions, heritage and innovation.”

Champollion retained a lifelong connection to Figeac. As I walked in his footsteps, I noticed myriad references to the great scholar, but I also fell under the charm of the town’s architecture and ambiance. Figeac had been a major market hub in the 12th to 14th centuries but later declined during the Hundred Years’ War and the Wars of Religion. By the 20th century, the buildings in the town center were degraded and falling apart. It was Mayor Martin Malvy who, in the 1970s, championed a policy of heritage preservation. Since then, this priority has enlivened the city center by retaining local businesses. The revitalized central district was classified with historical protected status in 1986, and Figeac was awarded the “city of art and history” label in 1990.

The medieval edifices are museum-quality, but an even bigger draw for visitors is the town’s authenticity: This is a vibrant place where people live and work. “The Saturday market is an institution,” says local guide Aymeric Kurzawinski. “It’s been taking place here in the same place for a thousand years.” Designed in metal in the Parisian Baltard style, the covered market on Place Carnot is flanked by businesses such as the Mas butchery, the Champollion bookstore and the popular Sphinx restaurant, with tables spilling across the pavement.

Equally as packed is Café Champollion on Place Champollion. It faces the Champollion Museum, which incorporates the house where the scholar was born in 1790. Dedicated to the history of the world’s writings, the museum has an eye-catching double facade: Behind the original stone, a copper wall is carved with letter cutouts, filtering the light.

The Napoleonic origins of Egyptomania

Pyramids, sphinx, mummies: Ancient Egypt exudes a powerful attraction. Since the days of the Greeks and Romans, academics have hypothesized about the civilization that flourished for nearly three millennia along the life-giving Nile. This intrigue has only deepened over the centuries, with blockbuster museum exhibits breaking attendance records (such as “Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh” held in Paris in 2019) and new discoveries fueling the fire (the most recent being the May archaeological find of 250 sarcophagi in a necropolis near Cairo).

But there was perhaps no greater frenzy for Egypt than after Napoleon Bonaparte’s failed military campaign in Egypt in 1798. Champollion was 7 years old when this general with Pharaonic ambitions embarked on the expedition. Along with his soldiers, Napoleon brought a team of about 160 scientists and artists to gather research. It was an officer’s discovery of a mysterious stone that would change the course of history. The stone was inscribed with three types of writing (Greek script, Demotic Egyptian and hieroglyphics), thought to convey the same message. When the French were defeated by the British in 1801, the Rosetta Stone was seized, along with other antiquities, and now has pride of place in the British Museum.

Upon Napoleon’s return to Paris, his scholars amassed their observations into publications that together were known as “Description of Egypt” (published between 1809 and 1829). The books spawned a craze of Egyptomania that’s still visible in Paris today: sphinx sculptures, Egyptian water fountains, architectural friezes outside the Passage du Caire. There are even references underground in the obelisks painted on the walls of the Catacombs. Soon Europe was also gripped by an academic frenzy — both collaborative and competitive — to decrypt the Rosetta Stone. It was the puzzle of the era, not unlike today’s foremost scientific enigmas: developing mRNA vaccines to combat a pandemic and seeking solutions to the climate crisis.

The power of writing

“How could we forget this writing which existed right before our eyes?” said Vanessa Desclaux, one of the three curators, at the April preview of the “Champollion Adventure” exhibit at the National Library of France. Yet when Pharaonic Egypt became Christianized in the 4th century, the meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphics was lost for about 1,500 years. Over time, the characters were perceived not as a type of writing, but as pictograms. “They were considered pagan, magical symbols with an obscure meaning,” said curator Hélène Virenque.

It was a mystery that Champollion devoted his life to solving. Strides had been made by European scholars, particularly Thomas Young in England, but it was Champollion who would ultimately crack the code by determining the phonetic sounds of hieroglyphics. He made the leap because of his knowledge of the Coptic language, which is considered the living link to ancient Egyptian. An obsessive polyglot, he had learned over a dozen languages as a child. “He had a unique skill in understanding Coptic,” said Guillemette Andreu-Lanoë, curator and honorary director of Egyptian antiquities at the Louvre. “He also had a strong will, retracing his steps and going back over his mistakes.”

Throughout the 14-year process, he meticulously copied inscriptions from steles, statues and papyrus. His calligraphy was painstaking and perfect, much like the Egyptian scribes whose work on scrolls of papyrus was revered above that of all other professions. “Je tiens l’affaire!” (“I’ve got it!”) Champollion shouted to his brother when he finally solved the puzzle at age 32 on Rue Mazarine in Paris.

Running until July 24, the National Library exhibit was conceived as an immersion into the decipherer’s methodology and scientific approach, rather than a chronology of his life. His discovery wasn’t a flash of genius but the result of rigorous trial and error. “I sleep two or three times a week with the Rosetta inscription,” he wrote in June 1814. “So far I’ve only gained headaches and two or three words.” His color-coded pages are exhibited next to some of the artifacts he studied; other highlights include the Padiimenipet sarcophagus, the Prisse papyrus (nicknamed “the oldest book in the world”) and — my favorite — the sunglasses Champollion wore on his expedition.

The Louvre and its pyramid

Champollion’s discovery opened up an entire world. By studying Egyptian literature, scholars could understand millennia-old traditions, funerary rites and everyday life under the pharaohs. It was this approach that Champollion brought to the Louvre when King Charles X appointed him to oversee the newly acquired Egyptian collections.

“Champollion was revolutionary, because he obtained a place for ancient Egypt as a civilization,” says Vincent Rondot, director of the Egyptian antiquities department at the Louvre. “His accomplishment was to show the humanity behind the idea of Egypt, the global totality: the peasants who worked in the fields, the civil society, the pharaohs. … And because of this, he fundamentally changed humanity’s worldview.”

Under Champollion, the Louvre took a step toward its modern incarnation. “The 1827 inauguration of the Musée Egyptian was an important symbolic date because of the Louvre’s definitive transformation from the palace of the kings of France to a museum,” Rondot says. Now the world’s most-visited museum, the Louvre has an exceptional Egyptian arts collection, a reminder of which looms large in the vast courtyard. The glass-and-steel pyramid, designed by I.M. Pei as a new entrance and completed in 1988, was built with the exact proportions, on a smaller scale, as the Great Pyramid of Giza.

The Louvre’s Egyptologists continue Champollion’s mission — even expanding our perspective into the African continent. For a decade, the Louvre sponsored archaeological excavations in the Nubian Desert of Sudan, and the mission resumes in 2022 at El-Hassa, not far from the pyramids of Meroë. Showing at the Louvre until July 25, the “Pharaoh of the Two Lands” exhibit reveals a trove of artifacts associated with the Kushite kings, who briefly ruled Egypt in the 8th century B.C. Having conquered their Egyptian conquerors, these “Black pharaohs” ruled over a kingdom stretching from the Mediterranean to present-day Khartoum.

A short walk from the Louvre’s pyramid is another important symbol of ancient Egypt: The Luxor Obelisk presides over the Place de la Concorde and one of the prettiest panoramas in Paris. Now a city icon, it was a diplomatic gift from Muhammad Ali, the viceroy and pasha who is considered the founder of modern Egypt. (In that era, the country’s antiquities were the direct property of the viceroy. It would be another passionate French Egyptologist, Auguste Mariette, who established Egypt’s antiquities service to safeguard heritage.) The viceroy initially offered two obelisks from Alexandria, the so-called Cleopatra’s needles, but Champollion suggested the Luxor Obelisks as a substitute, because of the exquisite quality of their hieroglyphics. (Instead the Alexandria obelisks were offered to Britain and the United States, and they can be found today in London on the Victoria Embankment and New York outside the Met in Central Park.)

The journey to transport the Luxor Obelisk to Paris was so long and expensive that the second never made the trip. (President François Mitterrand officially “returned” it to Egypt in 1981.) A flat-bottomed boat was custom-built in Toulon to fit under the Paris bridges, then there was a months-long wait for the Nile to flood, not to mention the technical installation in Paris that required three years. In fact, Champollion didn’t live to see it erected on the Place de la Concorde. He died in 1832, exhausted after the expedition to Egypt he finally made in 1828-1829. His tomb in Père-Lachaise Cemetery is marked with an obelisk.

Two centuries after Champollion’s illuminating achievement, the Luxor Obelisk has emerged from a six-month restoration that removed urban grime and pollution. The original pink color of the Aswan granite is once again visible, the hieroglyphics gloriously legible. The oldest monument in Paris — dating to the 13th century B.C. — now captures the light the way the ancient Egyptians intended.

Nicklin is a writer based in Paris. Her website is marywinstonnicklin.com. Find her on Twitter: @MaryWNicklin.

Where to stay

Mercure Figeac Viguier du Roy

52 Rue Emile Zola, Figeac

011-33-565-500-505

This hotel is a heritage site beloved by locals who drop by for drinks or strolls in the garden. There are only 33 guest rooms, spread out in an ensemble of medieval houses, connected by courtyards and salons dressed in period feature. Contemporary decor pays tribute to Champollion, with references to writing. Rates from about $135 per night in summer.

Where to eat

La Racine et la Moelle

6 Rue du Consulat, Figeac

011-33-983-538-158

A favorite of the Figeacois, this friendly bistro is run by a French-Irish couple who previously trained in popular Paris restaurants. The menu focuses on seasonal ingredients sourced locally from producers. Open Tuesday through Saturday for lunch and dinner. (Closed Wednesday dinner.) Mains about $19.

What to do

Louvre Museum

Rue de Rivoli, Paris

011-33-140-205-317

Champollion was the first curator of the Louvre’s Egyptian collections. “Pharaoh of the Two Lands,” which focuses on the Kushite kings who once ruled Egypt, runs until July 25. Open daily, 9 a.m. to 6 p.m., and until 9:45 p.m. on Friday. Last entry one hour before closing. Closed Tuesday. Tickets about $18 per person. Free for visitors under 18.

National Library of France

Bibliothèque François-Mitterrand, Galerie 2

Quai François Mauriac, East Entry

011-33-153-794-949

Located in the 13th arrondissement, the François-Mitterrand site of the National Library was designed by architect Dominique Perrault as towers resembling open books. The “Champollion Adventure” exhibit showcases Champollion’s manuscripts alongside loaned artifacts and prized items from the library’s collection. Exhibit open until July 24. Open Tuesday to Saturday, 10 a.m. to 7 p.m., and Sunday, 1 to 7 p.m. Tickets about $9 per person; reduced-price tickets for students under 35, teachers and more about $7 per person.

“Eurêka!” in Greater Figeac

Champollion’s birthplace is celebrating the bicentennial of the decipherment with a program of events concluding in October. Highlights include concerts, culinary dishes, a special exhibit at the Champollion museum, and a sound and light show. Check website for full program.

Arab World Institute

1 Rue des Fossés Saint-Bernard, Paris

011- 33-140-513-838

The Jean Nouvel-designed landmark is hosting a virtual-reality experience called “The Horizon of Khufu: A Journey in Ancient Egypt,” developed in partnership with Peter Der Manuelian, an Egyptology professor at Harvard University and director of the Giza Project. Wearing a headset device, visitors take a 45-minute virtual trip inside the Great Pyramid of Khufu. Runs through Oct. 2. Open Tuesday to Friday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., and Saturday and Sunday until 7 p.m. Closed Monday. Tickets for virtual-reality experience about $31 per person.

Louvre-Lens

99 Rue Paul Bert, Lens

011-33-321-186-262

The first Louvre outpost, which is celebrating its 10th anniversary this year, was built on a former coal mine. For the bicentennial, an exhibit called “Champollion: The Path of Hieroglyphics” will take place from Sept. 28 to Jan. 16. Open daily, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Closed Tuesday. Admission to the Galerie du Temps and Pavillon de Verre is free. Tickets for temporary exhibitions about $12 per person. Tickets for people 18 to 25 about $6 per person. Free for under 18.

7 Promenade Robert Laffont (Esplanade du J4), Marseille

011-33-484-351-313

Mucem — Museum of Civilizations of Europe and the Mediterranean is running the “Pharaoh Superstars” exhibit until Oct. 17. Open daily, 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. Closed Tuesday. Closes at 8 p.m. from July 9 to Aug. 30. Tickets about $12 per person.

Champollion Museum

45 Rue Champollion, Vif

011-33-457-588-850

Champollion was raised by his brother Jacques-Joseph in the town of Vif, and their former home is a museum. The permanent exhibit shows how they contributed to the founding of Egyptology. During this bicentennial year, “Restoring Ancient Egypt” shows Jean-Claude Golvin’s watercolors until Sept. 18. Additional Champollion exhibits planned in the Isère department in the fall. Open Tuesday to Sunday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. until Oct. 31; closed for lunch, 12:30 p.m. to 1:30. Closed Monday. Free entry. Reservations recommended.

Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon

20 Place des Terreaux, Lyon

011-33-472-101-740

Running from Oct. 1 to Dec. 31, the “François Artaud — Jean-François Champollion” exhibit will show how the museum’s first director aided Champollion in his research. Open Wednesday to Monday, 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., and Friday, 10:30 a.m. to 6 p.m. Closed Tuesday. General admission about $8 per person; free for those under 18.

Collège de France

11 Place Marcelin Berthelot, Paris

011-33-144-271-211

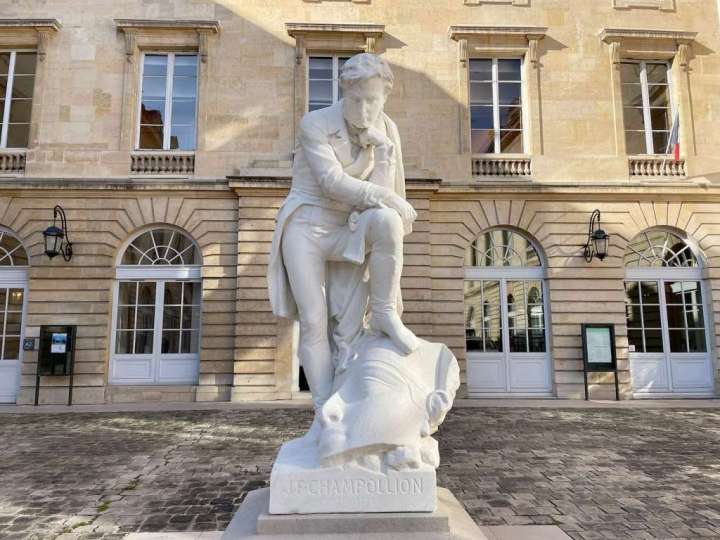

Champollion was appointed the first chair of Egyptology here in 1831. His statue, channeling Rodin’s “The Thinker,” is found in the courtyard. A Champollion exhibit will take place Sept. 15 to Oct. 28.

Information

PLEASE NOTE

Potential travelers should take local and national public health directives regarding the pandemic into consideration before planning any trips. Travel health notice information can be found on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s interactive map showing travel recommendations by destination and the CDC’s travel health notice webpage.