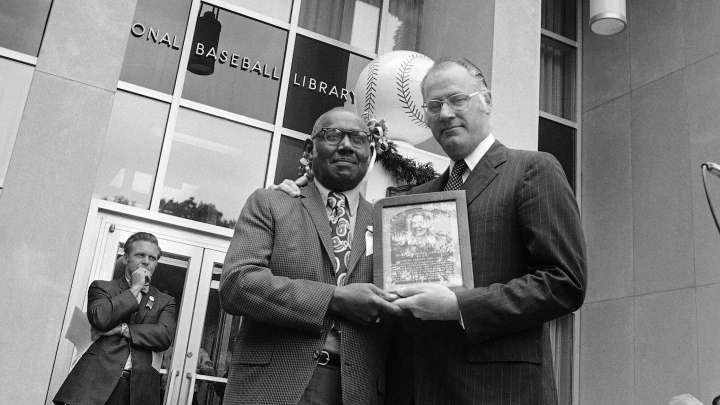

“Wake up, Dad,” said Josh Gibson Jr., “you just made it in.”

It’s been 50 years since Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard made Hall of Fame history

Gibson, the best Negro League hitter of all time, died of a stroke at 35 in January 1947, just three months before Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. Leonard, who turned 40 that season, retired soon thereafter.

“We in the Negro Leagues felt we could have and should have been in the majors, but it wasn’t meant to be,” Leonard said in his acceptance speech on that cloudy summer day 50 years ago, a month before his 65th birthday. “… We felt we were contributing something to baseball, too. We played with a round ball and round bats, and we loved it and liked to play — because there wasn’t that much money in it. My getting in is something I never thought would happen.”

Gibson, a catcher, and Leonard, a first baseman, powered a “Murderers’ Row” Grays team, which dominated the Negro National League in the 1930s and ’40s. The Grays split their time between D.C. and Pittsburgh, often outdrawing the Washington Senators in their own ballpark, Griffith Stadium.

The duo were inducted with six other players, including Dodgers pitcher Sandy Koufax and Yankees catcher Yogi Berra.

“They scarcely could have been more representative of Melting Pot USA,” the Sporting News wrote at the time, describing the five living inductees. “Humble and appreciative, they stood before a microphone in typically small-town USA. … A Jew from New York, an Italian from Missouri, a Scotch-Irish-Indian from Alabama, a Spaniard from California and a Negro from North Carolina.”

Gibson and Leonard were just the fourth and fifth Black players to make the Hall of Fame, following Robinson (1962), his Brooklyn Dodgers teammate Roy Campanella (1969) and Satchel Paige, who in 1971 became the first player inducted by the Committee on Negro League Veterans. (All three had played in the Negro Leagues, but Paige was the only one of the three who played most of his career there.)

Some news coverage that day characterized Gibson and Leonard as at best supporting actors. In its story about the induction, the New York Times reported, “In a perfectly appropriate blend of sentiment, humor and brevity, Yogi Berra, Sandy Koufax, Lefty Gomez and five less glamorized figures were inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame today.”

Fifty years later, it would be hard for any baseball historian to consider Gibson and Leonard “less glamorized” than other Hall of Famers. According to Baseball-Reference, Gibson finished with a career batting average of .374, a .720 slugging percentage and an off-the-charts 1.178 on-base-plus-slugging percentage. Leonard had a .345 career batting average and a 1.042 OPS.

“Josh was the greatest hitter I ever pitched to, and I pitched to everybody,” Paige said in 1972, according to the Times. “There’s been some great hitters — Williams, DiMaggio, Musial, Mays, Mantle. But none of them was as great as Josh.”

Campanella, a star slugging catcher who played eight seasons in the Negro Leagues before joining the Dodgers in 1948, told the Sporting News: “Whenever I played on an all-star team in the Black leagues with Josh, he was the catcher. I played third base. Everything I could do, Josh could do better.”

‘Too bad this Gibson is a colored fellow’

Gibson and Leonard, of course, didn’t come out of nowhere. During spring training in 1939, former Senators star Walter Johnson, one of the best pitchers in baseball history, watched Gibson play in a game in Orlando, then raved to Washington Post sports columnist Shirley Povich, who quoted him:

“There is a catcher that any big league club would like to buy for $200,000. I’ve heard of him before. His name is Gibson. They call him ‘Hoot’ Gibson, and he can do everything. He hits that ball a mile. And he catches so easy he might just as well be in a rocking chair. Throws like a rifle. [Yankees star] Bill Dickey isn’t as good a catcher. Too bad this Gibson is a colored fellow.”

Povich added: “That was the general impression among the Nats who saw the game.”

Senators owner Clark Griffith came to the same conclusion a few years later, although he knocked the price down a bit. “There’s a catcher worth $150,000 of anybody’s money right now. If I could have had him, I’d have gone after him some time ago!” he gushed to The Post in 1942. Griffith recalled seeing Gibson hit four homers in a doubleheader the year before, one of which was the longest ball ever hit at Griffith Stadium.

And yet Griffith resisted pressure from Black journalists such as Sam Lacy to sign Gibson and other Black players — and instantly improve his mediocre team. Leonard recalled that one day around 1942, Griffith asked to meet with him and Gibson, according to a 1988 Post story by John B. Holway, adapted from his book “Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers.”

At that meeting, Leonard recalled, Griffith mentioned the campaign by Black sportswriters to put them on the Senators roster, then said: “Well, let me tell you something: If we get you boys, we’re going to get the best ones. It’s going to break up your league. Now what do you think of that?”

Leonard said they replied that they would be happy to play in the major leagues but would leave it to others to make the case. According to Holway, the duo never heard from Griffith again.

A Josh Gibson MVP Award?

Two years ago, the Baseball Writers’ Association of the America voted to remove former commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis’s name from MVP plaques. There were no Black players in the major leagues during his long tenure as the sport’s first commissioner, from 1920 to 1944. Now the Josh Gibson Foundation has a campaign to rename the MVP for Gibson.

“We all know that Kenesaw Mountain Landis denied over 3,400 men an opportunity to play in the major leagues,” the group’s executive director, Sean Gibson, Josh Gibson’s great-grandson, said in a recent telephone interview. “So having Josh Gibson’s name on the MVP award would not just represent Josh Gibson, but it would represent the 3,400 men who were denied the opportunity to play in the majors. This is bigger than just Josh Gibson. Josh is carrying those guys on his shoulders.”

He added that it would be “poetic justice” for a player denied the chance to play in the major leagues to replace a commissioner who had been an obstacle.

Sean Gibson said that his grandfather, who accepted the Hall of Fame plaque for Josh Gibson, always credited Boston Red Sox star Ted Williams for opening the door to players such as Gibson to make the Hall. In his 1966 Hall of Fame induction speech, Williams said, “I hope that someday the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way could be added as a symbol of the great Negro players that are not here only because they were not given a chance.”

“Five years later, Satch goes in in ’71,” Gibson noted. “The next year, ’72, is Josh. My grandfather always gave Ted Williams credit, because he feels if Ted Williams does not mention Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige in his speech, he doesn’t know if that happens that fast.”

Gibson said he thinks that Williams’s background — his mother was Mexican American — helped him feel compassion for Negro League players. Another factor was Williams seeing Black players during barnstorming games against Negro Leaguers.

“So he knew about the talent,” Gibson said. “He knew how great these guys were on the diamond.

“Ted spoke up; nobody else spoke up,” he added. “So we’re very grateful for that. His speech was only, like, three minutes long. And for him to include that small piece of the pie, of Josh and Satch, was huge for us.”