Masih Alinejad is an Iranian journalist, author and women’s rights campaigner. A member of the Human Rights Foundation’s International Council, she hosts “Tablet,” a talk show on Voice of America’s Persian service.

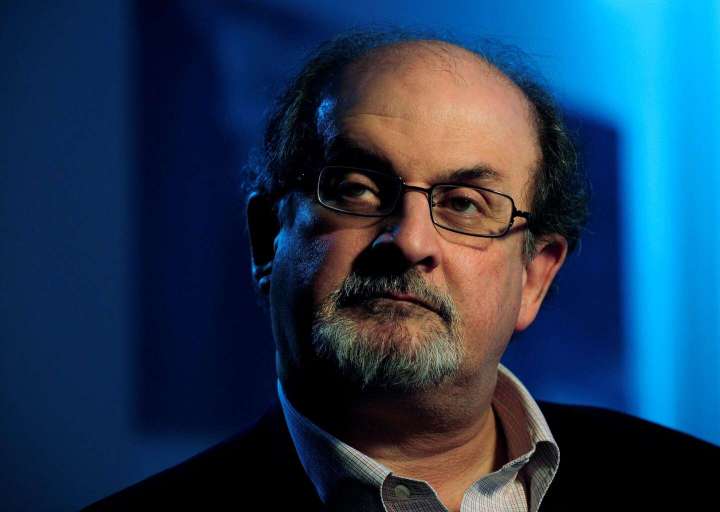

Life in a safe house: Why I sympathize with Salman Rushdie

The attack on Rushdie was an act of terrorism. That’s what President Biden and other Western leaders should call it. The media in Iran have been celebrating it, regretting only that the assailant didn’t manage to kill Rushdie. The brutal regime in Tehran has a history of encouraging acts of violence to undermine our freedoms. Why aren’t we taking a stronger stand?

The attack on Rushdie struck especially close to home for me. I, too, have been repeatedly targeted by the vicious regime in Tehran for my criticisms of its hateful policies against women. Two weeks ago, I got a lucky break: Police arrested a man with a loaded AK-47-style rifle in his car after he made a failed attempt to enter my house in Brooklyn. The incident recalls another plot foiled by the FBI in 2021, when federal prosecutors charged four alleged Iranian agents with conspiring to kidnap me and take me back to Iran. At the time, I had to go into hiding for a while; now the FBI has put me under its protection again.

Now I find myself living in a safe house with featureless white walls adorned with replica modern paintings; this is where I was when I learned about the attack on Rushdie. It might be safe, but it’s not my home. Until two weeks ago, I lived in a beautiful house in Brooklyn surrounded by loving neighbors who, since my unwilling departure, have been watering my flower beds in solidarity with my plight. Since the attack on Rushdie, the official Telegram channel of the Revolutionary Guard Corps and others in Iran on social media have been praising the would-be killer. They’ve also been saying that I should be next.

Rushdie himself knows only too well what this situation is like. After Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa in 1989 calling for the author to be killed over his book “The Satanic Verses” (which Khomeini deemed offensive to Muslims), Rushdie ended up living in a safe house for most of the next 10 years. That lifestyle took its toll. By around 2001, he was sick of the living in the shadows and began making public appearances again. He even wrote a memoir about his experience. Everything seemed fine.

After years on the run, Rushdie might have concluded that he had regained his freedom. Now that assumption is over. In fact, Khomeini’s threat against him was never lifted; Iran’s current supreme leader affirmed the original fatwa on Twitter as recently as 2019, and the bounty for killing Rushdie now stands at more than $3 million. Apologists claiming there is no link with Iran should consider the headline with which the main state newspaper in Tehran celebrated Mr. Rushdie’s wound: “Satan’s eye has been blinded.”

I have often thought of Rushdie and his plight over the past two years when my own journey in and out of safe houses first began. I often wondered how Rushdie coped with the physical and mental hardships of enforced imprisonment. To be in a safe house is like being back in quarantine — except that there seems to be no vaccine against the fanaticism of the Iranian regime.

The fact that a religious fundamentalist regime issues fatwas against those who criticize them is not surprising. What is shocking is the lack of action from democratic governments around the world, which should be categorically denouncing these actions. In the sleepy town of Chautauqua, N.Y., Rushdie was about to lead a discussion about the role of the United States as a haven for exiled writers and other artists under threat of persecution. The irony is not lost on me.

I have no intention of disappearing from public view. The activist in me wonders how many more times someone on U.S. soil will be a target of the Iranian regime and its supporters before concrete action is taken. The other part of me wonders whether I will be able to do banal, normal things such as walking to the local bakery or sitting outside on a winter day and drinking hot chocolate.

What has driven so much of the intensity of my activism is a sense of obligation and camaraderie with the many women, journalists and human rights activists who have stood up for liberal values inside Iran and paid a steep price. I owe it to them to use the freedoms I have enjoyed in Western democracies to give them a voice. I do not want to die and will have to take precautions, but I intend to live a life free from fear, with a garden and loving neighbors, no matter what it takes. I hope Rushdie recovers quickly. One day I’d like to thank him — and maybe even show him our flower beds.