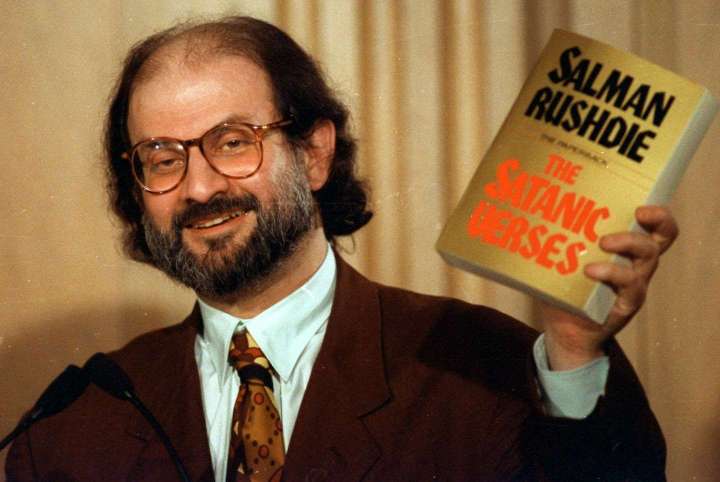

In the aftermath of the appalling attack on author Salman Rushdie, his novel “The Satanic Verses” made a striking return to the bestseller list. Let’s hope people read their new acquisition, and not just to see what the 33-year-old fatwa is all about.

You should read ‘The Satanic Verses’ — and not just for the controversy

Then-Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini apparently never read “The Satanic Verses” before or after he issued his murderous judgment against the book in 1989. I imagine that wouldn’t have surprised Rushdie. Among the characters in “The Satanic Verses” is an imam who avoids looking at the country that has given him refuge so he will “be able to say that he remained in complete ignorance of the Sodom in which he had been obliged to wait.” But then, a close reading of the text was never the point. As Robin Wright explained in the New Yorker, the fatwa was about Iranian domestic politics, not a careful parsing of whether a fictional schizophrenic’s dreams ought to be taken as Rushdie insulting Islam.

The best possible resistance to the reduction of literature to an instrument is, of course, to read. In pure aesthetic terms, “The Satanic Verses” is a delight: funny, broadly erudite and wrenchingly gorgeous. And as a matter of politics and religion, this novel embodies the unique ideological power of art: to push beyond what’s possible, to say what would be too costly for actors in another arena to speak aloud, to expand the audience’s sense of what the world can be.

Art itself is one of the many subjects of “The Satanic Verses.” The book’s two main characters are Indian actors: one a star of Bollywood theological dramas, the other an assimilated voice actor. Both men are passengers on a hijacked plane, and when it’s bombed, they survive, but are transformed in the fall. Gibreel Farishta, who portrayed gods, finds himself possessed of a halo. Saladin Chamcha, the so-called man of a thousand voices, grows horns, hooves and a tail, and acquires a terrible case of halitosis.

Their duality is a way for Rushdie to explore religion, specifically the question of prophetic certainty. But to treat “The Satanic Verses” as only, or even primarily, a religious novel is to miss the point and to undersell its scope. Gibreel and Saladin represent a tussle between India and Britain, between a melting pot and a glorious cultural bouillabaisse, mysticism and rationality, the best impulses and the worst, culture high and low. Rushdie has sympathy for people on both sides of these many divides, be they prophets or the angels from which visionaries extract their revelations, cheating wives or cuckolded husbands, assimilationists or separatists.

Rushdie has a Dickensian gift for names; one of the passengers on the hijacked plane is a creationist named Eugene Dumsday. He sends his angel to a music shop to pick out a trumpet and his devil to a racial justice meeting in formalwear. The characters attend a party for a truly awful-sounding musical adaptation of “Our Mutual Friend” and argue about political philosophers like Antonio Gramsci and Frantz Fanon. James Baldwin, Daniel Defoe and Herman Melville haunt the text, as do ghosts on flying carpets and in tartan tam-o’-shanters. “The Satanic Verses” is full of chains of butterflies leading pilgrims back to each other, a burned tree that once contained an expatriate’s soul, and reels of film that spontaneously combust.

Certainly, there are books that are most notable for the offense they give or the controversy they spark. No one deserves death sentences for writing those books; if literary genius is no defense against a fatwa, mediocrity is still protected by freedom of expression.

But a book that gives offense may have a great deal more to offer as well. That’s a lesson worth keeping in mind for those of us unmoved by the charge that “The Satanic Verses” is blasphemous. When the day inevitably comes when we find ourselves taken aback by a work of art, better to do as the writer Ray Bradbury suggested in “Zen in the Art of Writing,” and “behold beauty yet perceive its flaw / Then, flaw discovered like fair beauty’s mole, / Haste back to reckon all entire, the Whole.”

To allow things we might dislike or be disgusted by — much less a bad-faith non-reading of a great book — to loom over everything else about a work of art is to shrink down the world to the comprehensible and the comforting, at the potential cost of transcendence.

“A book is a product of a pact with the Devil that inverts the Faustian contract,” Rushdie wrote in a startlingly prophetic passage in “The Satanic Verses. “Dr. Faustus sacrificed eternity in return for two dozen years of power; the writer agrees to the ruination of his life, and gains (but only if he’s lucky) maybe not eternity, but posterity, at least.”

Salman Rushdie should enter posterity not merely for his courage, but also for the beauty he brought into the world.