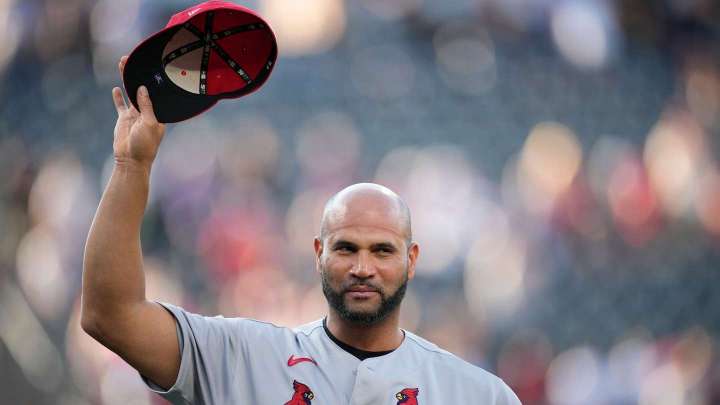

Albert Pujols played the first half of this season like an aging Willie Mays. He’s playing the second half like an ageless Tom Brady.

Albert Pujols has defied age — and the specter of Willie Mays in twilight

Mays was one of the greatest players of all time, but his final season of 1973, at age 42, was a textbook case of an athlete staying on too long. A lifetime .302 hitter who played a peerless center field, Mays hit just .211 with a .647 on-base-plus-slugging percentage that year and famously misplayed a flyball in the World Series.

When the St. Louis Cardinals and Pujols announced in March that the future Hall of Famer had signed as a free agent to finish his career with his original team, some worried he might be repeating Mays’s mistake. Pujols, also 42, stressed this was a baseball decision, not a nostalgic one.

“They believe I can still play this game, and they believe I can help this organization win a championship. And myself, I believe in that, too,” he said at a news conference.

Yet through the first three months of the season, Pujols looked even worse than the 1973 version of Mays. On July 4 he was hitting just .189 with a .601 OPS — and trending in the wrong direction. After a decent start, Pujols hit .188 in May and .158 in June. He had a measly four homers. This season had all the hallmarks of a Willie Mays redux.

Then it changed. Since the all-star break, Pujols has been one of the game’s best hitters, batting .366 with a .756 slugging percentage through Saturday’s games. Pujols is also chasing 700 home runs — he is just five away — which seemed an impossibility earlier this season. Last month, his 1.224 OPS topped all major leaguers with at least 65 plate appearances, as the Athletic’s Jayson Stark noted.

Longtime St. Louis sports columnist Bernie Miklasz recently wrote that Pujols “isn’t embarrassing himself. Pujols isn’t the old, sad, worn-down and out-of-shape Elvis. Pujols is performing like the 1968 Elvis — the one that made a stunningly successful comeback on a nationally televised NBC special.”

‘Like coming back to paradise’

When Pujols left the Cardinals as a free agent after the 2011 season to sign a 10-year contract with the Los Angeles Angels, it crushed many St. Louis fans. But that was nothing compared to the loss New York City baseball fans felt in 1958, after the Giants left for San Francisco and the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to Los Angeles. New Yorkers especially missed Mays, who in his final season in the Big Apple led the National League in slugging percentage, stolen bases and triples — a trio of feats that demonstrated his unfathomable combination of speed and power.

The Mets — who began play in 1962 and were the laughingstock of the NL for their first few seasons — brought back some of the old stars from the Dodgers who were well past their prime, such as first baseman Gil Hodges and center fielder Duke Snider. They had their sights on Mays in those early days, too.

In May 1963, the team honored him at a “Willie Mays Night” at the Polo Grounds, the Giants’ old ballpark that the Mets used before moving into Shea Stadium. That same day, the city declared “Willie Mays Day” in Manhattan.

“I feel like this is my home,” Mays said at that night’s festivities, still in his prime days before his 32nd birthday.

William A. Shea, the lawyer who is credited with bringing National League baseball back to New York, cut right to the chase in making a plea to Giants owner Horace Stoneham:

“We got Gil Hodges back from the coast and Duke Snider back. We love them, and we love you, Willie. When, Mr. Stoneham, are you going to give us our Willie back?”

The answer, as it turned out, was almost exactly nine years later, when the Mets acquired him in May 1972 from the Giants for pitcher Charlie Williams and $50,000. The deal was consummated in a New York hotel; participants included Mays, Stoneham, Mets board chairman Donald Grant and team manager Yogi Berra. When the four men came downstairs, the New York Times reported, “the lobby vibrated with the kind of tension a heavyweight boxing champion generates when he walks down the aisle to defend his title.”

At the time of the trade, the Mets were in first place in the NL East, 13-6, while the Giants were languishing at the bottom of the NL West at 8-16. Mays, 41, had gotten off to a slow start, too, hitting just .184 with San Francisco, but expressed confidence he had something left in the tank.

“When you come back to New York, it’s like coming back to paradise,” Mays told reporters. “I’m here to play. The Mets have a good team, and they’re not going to put me out there just because my name is Willie Mays. But I think I can still play.”

“I’m looking forward to playing and helping but not to embarrassing myself,” he added.

In a recent interview with USA Today, Pujols sounded a similar note.

“It’s been awesome having the opportunity to come back to St. Louis where everything started for me 21 years ago,” said Pujols, who like Mays has been welcomed back by adoring fans. “This organization believed I can help. It wasn’t just come back to celebrate my last year. It was knowing I can help”

‘I can’t even mention the word “retire” to him’

When people think of Mays’s Mets’ days, they naturally think of his last over-the-hill ’73 season. Mostly forgotten is his decent first year with the Mets, when he hit .267 with an .848 OPS in that down year of 1972, when the sport’s batting average was just .244.

The wheels came off in an injury-marred 1973 season, however, which included swollen knees, an inflamed shoulder and cracked ribs.

“Cary Grant retired so he didn’t have to watch himself get older on the screen,” Steve Rushin wrote in Sports Illustrated last year. “Mays did no such thing.”

Unlike Pujols this year, Mays didn’t announce before the season that it would be his last, which made the situation delicate for the Mets as it became clear the end was near.

“I can’t even mention the word ‘retire’ to him,” Grant, the team board chairman, said in early September. “It’s a sensitive thing with Willie, and he means too much to us all to be pressed on a decision.”

“I want to play as long as I can help,” Mays said around that time. “I’ve always said that I’ll quit when it’s no longer fun for me or no longer any help to the team.”

Finally on Sept. 20 — with the Mets in the midst of a furious late-season rally that would help them barely claim the division title under the slogan “Ya Gotta Believe” — Mays announced he was retiring at the end of the season.

“It’s been a wonderful 22 years, and I’m not just getting out of baseball because I’m hurt. I just feel that the people of America shouldn’t have to see a guy play who can’t produce,” he told a packed news conference at Shea Stadium.

He expressed appreciation for New York fans: “I’m not ashamed of the way things have gone the last couple of months. They didn’t run me out. In San Francisco, I don’t think I would have played this year. The people would have run me out of the city. In New York, they let me hit .211.”

The team honored him with a second “Willie Mays Night” a few days later, when 50,000 fans gave him a raucous send-off at Shea Stadium on an autumn evening in Queens in the midst of a pennant race. Mays looked youthful in a Mets jacket and baseball cap, occasionally dabbing tears from his face.

“I never felt that I would ever quit baseball,” he said. “But as you know it always comes a time for someone to get out.”

The Mets honored Mays again last weekend when they retired his number — fulfilling a promise Mets owner Joan Payson had made to him a half-century ago. (She died in 1975.)

Mays ended his career third in home runs with 660. He has since been passed by Barry Bonds, Alex Rodriguez and, two years ago, Pujols.

The Mets won the division in 1973 with an 82-79 record, then stunned the Cincinnati Reds in the NL Championship Series to win their second pennant in five years. Mays returned for the postseason, going 1 for 3 in the NLCS.

In the second game of the World Series against the Oakland Athletics, he displayed both his talent and ebbing skills. Mays misplayed a flyball in the bottom of the ninth inning, helping the A’s tie the game, then singled in the go-ahead run in the 12th inning, pacing the Mets’ series-tying win. Oakland wound up winning the series in seven games.

The Cardinals primarily use Pujols — who has called himself “the grandpa in this clubhouse” — as a designated hitter, so he’s unlikely to face any defensive challenges this fall. Some have suggested he should even consider returning next season, especially if he’s still chasing 700 homers, but Pujols has demurred.

Any mention of Pujols in the same breath as Mays is now about milestones, not mistakes. For example, Pujols’s two-homer game on Aug. 20 was his 64th multihomer game — breaking a tie with Mays for fifth place all time.