Not long after the New York Times bought the Athletic earlier this year, the founders of the popular sports website held an all-staff call.

At the Athletic and New York Times, a marriage with promise and tension

Still, there was an important matter the Athletic’s founders, Alex Mather and Adam Hansmann, needed to clarify with their newsroom of 400-plus journalists. Despite the fact that the Times now owned the Athletic, the founders reminded their employees, they were not to start telling sources that they worked for the Times.

Times sportswriters had worried to higher-ups that Athletic reporters, potential competitors, had been introducing themselves as Times journalists. One Athletic staffer, who had snapped a photo in front of the Times building in Manhattan and called it his new office, was asked to take it down.

Eventually, the Athletic created a policy clarifying the issue: “Always identify yourself specifically as a representative of The Athletic (and not the New York Times).” But nearly 10 months after the purchase, the question at the heart of that conference call, of what the Athletic will become as it is integrated into the Times, remains largely unanswered. How it is answered will help shape the sports media landscape for years to come.

The Athletic was founded in 2016 on a simple premise: That if you created online versions of local sports sections and gave them the resources to exhaustively cover teams, readers would flock. It launched in Chicago and spread across the United States and Canada, then added robust Premier League coverage in the United Kingdom, helped by $140 million in venture funding. It weathered the pandemic and, by 2021, boasted 1 million subscribers. Like start-ups do, it went looking for an off-ramp, culminating with the sale to the Times.

Mather once bragged — to the Times, no less — that the Athletic would let local papers “continuously bleed until we are the last ones standing.” Now that the Athletic was owned by a newspaper, the jokes were easy to make. But the Times isn’t (just) a newspaper anymore, and it’s certainly not a local one. It’s a games company and a recipes app, a consumer advice site and a podcast producer, all with a side of news.

Perhaps a greater irony of the purchase was that the Times several years ago decided that it didn’t want to be in the business of aggressively covering local sports and de-emphasized much of its traditional sports coverage. With the Athletic, the Times was now very much in the business of local sports. And critically so.

The Times wants the Athletic to be profitable in three years, but it’s losing money now: $6.8 million in February and March of this year and another $12.6 million in the second quarter, according to the Times public filings, which is a significant drag on the company’s bottom line.

“This is a very big bet,” said David Perpich, head of new products at the Times and publisher of the Athletic. “It’s a very big investment that we believe in, and that we’re going to get right.”

A million reasons

Part of the Sulzberger family that owns the Times, Perpich was working as a management consultant when he urged the Times to adopt a paywall in 2011. He then joined the company full-time and helped create the product division that launched the cooking and games apps. As head of the division, he also oversees Wirecutter, another Times acquisition, which offers advice and reviews for consumers.

In a conference room at the Times headquarters on a recent afternoon, Perpich said the Times’s internal research shows 100 million people in the United States read sports journalism, including 24 million with a willingness to pay for it. Seventeen million of those are open to paying the Times for it, he said.

As a company, the Times has set lofty goals for subscribers. It wanted 10 million by 2025 and delivered ahead of schedule, reaching that mark this year after adding around those million Athletic subscribers. (About 120,000 of the Athletic’s million paying customers were already Times subscribers, Perpich said.) Now the Times wants to hit 15 million by 2027, drawing users to news, cooking advice, games and, now, coverage of their favorite teams.

“The space for what the Athletic does is massive,” Perpich said. “And when you think about the different moments in somebody’s life, as you’re building an essential subscription, there’s the news; there’s food; there’s games. Sports is one of those big things as well. And that’s why we made the largest acquisition we have in 30 years.”

Perpich’s first order of business is to integrate the Athletic into the Times bundle. Recently, the company began allowing Times log-in credentials to be used for the Athletic, helping users realize the value of the larger bundle the Times offers (cooking, games and Wirecutter) for $25 every four weeks. The Athletic, alone, costs $8 per month or $72 per year.

The Times would also like to get the Athletic in front of more people. To that end, it has done some management shuffling, moving some of its search engine and ad sales brainpower to the Athletic. (The site is also currently looking to hire a new executive editor.) The Athletic, which earned less than $10 million in advertising last year, also announced a big expansion of the ad sales business this month. Perpich said other popular sports sites earn in the hundreds of millions of dollars, which the Athletic should use as a benchmark.

The Athletic can help bolster the Times’s international aspirations, Perpich said. He raved about the popularity of the site’s soccer coverage in the U.K. As for what has surprised him the most thus far, Perpich said it was the type of sports coverage that readers most want.

“The interest in what I would call roster construction — free agency, the draft, trades, player movement in general,” he said. “It’s just bigger than I think we realized. I think we thought like, oh, the Super Bowl is really big, but actually the NFL draft [is bigger].”

‘Dazzled’ by scoops

During a particularly futile New York Knicks season in 2015, the Times sports desk, which had dutifully covered the local teams for years, pulled its Knicks writer off the beat, announcing that the team was so bad it wasn’t worth their time. Instead, the paper ran a “Not the Knicks” series that sent its basketball writer across the globe, including to Australia and the lower divisions of college basketball, looking for other basketball stories.

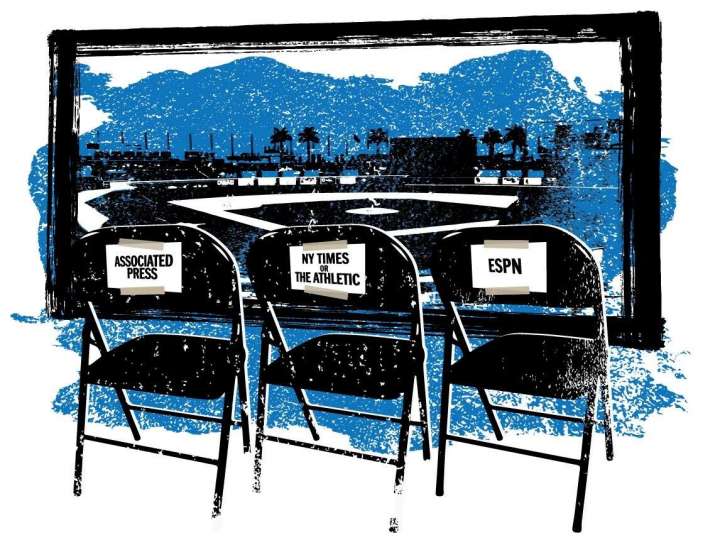

That strategy became an ethos of the Times sports desk, which focused less on more traditional sports coverage and more on, as one person in the newsroom put it, “ethereal stuff.” The paper today doesn’t have anyone traveling or attending games full-time for the Mets, Yankees, Knicks, Jets or Giants, though it does offer wall-to-wall coverage of tennis, the Olympics and the playoffs of major American sports.

While the section expanded internationally and does strong investigative reporting, New York sports fans have been less thrilled with the daily report. “A full page on some soccer stadium in Milan, Italy, 2/3rds of a page on a soccer team in England and nothing about the hometown @Yankees or @Mets games,” Ralph Nader tweeted earlier this year.

Perhaps it didn’t make sense for the Times to throw resources into local sports coverage as it added more national and international readers, but several people in the newsroom wondered if there had been an overreaction to the small readership on stories recapping that night’s game. It wasn’t that fans didn’t want coverage of their favorite teams; they just didn’t want to read recaps of what they could digest in a two-minute highlight video. (A Times spokesman said pageviews don’t drive newsroom coverage decisions.)

Several Times staffers noted the Athletic has been beefing up some of those missing hometown beats, putting multiple reporters on the Mets, Yankees and Giants, an acknowledgment that there is a demand for that coverage. To the Times, the difference is the intended audience.

“The Athletic is trying to get the attention of hardcore sports fans,” said Jason Stallman, a former Times sports editor who has helped with the Athletic’s transition. “The Times is targeting general interest readers who are curious about the world. Yes, there will be some overlap of those Venn diagrams, but they are generally not competing.”

The Times may not do all of what the Athletic does, but the Athletic does do plenty of the investigations and national features that the Times does; that kind of work can drive subscriptions, too: A revelatory Athletic report on abuse in the National Women’s Soccer League last year delivered more than 3,200 subscriptions.

The Times has started to promote the Athletic on its homepage and in its Twitter feed, which has sapped morale among the sports department of around 40 to 50 people, according to multiple staffers, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal company business. (The Times declined to confirm how many staffers were on its sports desk.) The sports staff has had a series of meetings with higher-ups at the Times, including Perpich and executive editor Joe Kahn, asking questions about how work is promoted and how and whether they are supposed to compete with the Athletic on stories. This summer, the Times and the Athletic ran identical stories about a Yankees pitcher in the span of a few days.

Times sports staffers have also asked repeated questions about standards at the Athletic, the Times staffers said. The Times has created a team to examine Athletic policies and, going forward, will limit or at least need to sign off on journalists authoring books with players they cover, as some British soccer reporters have. And some Athletic reporters chafed at the Times implementing restrictions on political donations and commentary on social media, as Defector reported.

There is tension over sourcing requirements, too, best personified by leading NBA reporter Shams Charania, who specializes in his lightning fast and exhaustive reporting of transactional news, which he always delivers first to his nearly 2 million Twitter followers. Indeed, the Athletic’s own reporters have raised concerns about his reporting when it veers beyond the narrow lane of transactions. Within the Times, there was some intrigue about whether Charania would re-sign with the Athletic, as a signal of whether the Times would embrace his kind of reporting. Perpich said breaking news was important for more visibility and that retaining Charania was a key priority, and he re-signed this month; the New York Post reported the deal was for a year.

At the same time, Charania also re-signed his TV deal with the network Stadium, which, according to a person with knowledge of it, was for seven figures. According to multiple familiar with the discussions, he has spoken to gambling companies, including FanDuel, about working for them as well. Asked if the Times would allow a reporter to be paid by a gambling company, Perpich said, “We allow gambling companies to advertise on the website. As long as someone isn’t putting themselves in danger of violating journalism and independence ethics, we would be supportive of that situation.”

As for whether insider reporting could exist within Times standards, Stallman said, “When we learned more about Shams and his methods, we were really, really impressed at how rigorous he is. Not only was there not any lingering concern over whether that worked under the Times imprimatur, but we were kind of dazzled by it.”

A test in Qatar

When the Athletic was sold, the cash trickled down to every writer at the site. Each received at least $5,000, while those with the largest equity stakes received upward of $1 million, according to several staffers. For many, it was justification for putting their faith in the company’s founders. That faith has been one key reason the newsroom has not unionized, staffers said, even amid a wave of organizing across digital media newsrooms.

The NewsGuild has worked with Athletic staffers on an organizing drive. At one point, amid the sales negotiations last year, Hansmann, one of the founders, expressed concern that a union campaign might interfere with a sale, according to a person who spoke with him. But multiple people familiar with the efforts said, as of today, unionization was not imminent. (The Times went through a contentious organizing effort after it acquired Wirecutter.)

One reason to unionize would be job protection, though Perpich was adamant the Times intended to keep the Athletic’s head count steady. But there is a bottom line to meet, and writers have felt the pressure of cost-cutting. The Athletic once had aspirations to blanket every professional and college team with beat reporters, but those have been scaled back. According to staffers, around 12 NBA and six NFL teams are without dedicated beat reporters, including the Miami Dolphins and Memphis Grizzlies. Several baseball teams who had been in the playoff hunt, including the Milwaukee Brewers and Houston Astros, don’t have beat writers, to the chagrin of those teams’ fans.

As beats are lost there is reason to worry about competition. ESPN has a subscription streaming service that includes writing from 32 NFL beat writers and a team of regional and national NBA and MLB writers. And while it is more expensive than the Athletic, it offers thousands of live games.

Rigorous beat reporting is also expensive. Ahead of the NBA playoffs, a number of writers were given short notice that they couldn’t travel, causing some to miss playoff games. Ahead of this coming season, NBA writers have each been allotted $2,100 for their entire travel budgets — flights, hotel and per diems — for the remainder of 2022, a paltry amount for any writer hoping to offer best-in-class beat coverage of a team. Writers have had to make hard decisions about how to budget the funds and when to travel, knowing they will have to miss most road games. For some, there is concern about what it signifies, while others are confident the budgets will be restored next year, as promised.

Perpich said that on aggregate, travel budgets for the entire site had been restored to pre-pandemic levels. He said he had no knowledge of the specifics of the NBA budgets.

If the Athletic’s newsroom were to unionize, it would almost certainly be its own bargaining unit, separate from the Times newsroom. And Times management would want it that way, rather than grow the current bargaining unit by hundreds of members. That is another reason that the Times would never want Athletic staffers to be able to say they are Times sportswriters, according to a person familiar with the Times-NewsGuild dynamic. Since the Times is committed to investing in the Athletic as a key tentpole of its subscription offering, one obvious way to cut some of its sports coverage costs, multiple staffers said, would be to shrink the Times’s sports desk, not through layoffs but by not filling jobs that come open.

The Times declined to comment on whether it planned to maintain the current size of its sports desk.

More clues to how the newsrooms will coexist could come this fall during the World Cup, an event that the Times has thrown extensive resources into covering in recent years. Perpich said it will be a major priority for the Athletic, too, with plans to send around 20 reporters to Qatar and have more covering from the U.K. and the United States.

But even if the two newsrooms are watching each other intently, Perpich said he is only watching one of them. “Honestly, I’m only really focused on the Athletic,” Perpich said. “I don’t make the decisions on what the [Times] newsroom does or does not cover.”