KYIV, Ukraine — The 2022 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded Friday to a trio of human rights defenders in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, delivering another pointed international rebuke of Russian President Vladimir Putin for his war in Ukraine, and condemnation of widespread abuses and repression by the Kremlin chief and his ally, Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko.

In rebuke of Putin, rights defenders in Ukraine, Russia, Belarus win Nobel

The prize committee named Ukraine’s Center for Civil Liberties (CCL), which is working to document alleged war crimes by the Russian invaders; the Russian human rights group Memorial; and imprisoned Belarusian human rights advocate Ales Bialiatski as its annual Peace Prize winners, marking the second consecutive year Putin critics were among those designated for the award.

“They have for many years promoted the right to criticize power and protect the fundamental rights of citizens,” the Norwegian Nobel Committee said in announcing the winners.

Although the committee did not name Putin or Lukashenko in its announcement, it was another high-profile reproach of the oppressive means their governments have embraced to abuse power and silence opponents at home and abroad.

Lukashenko, who has brutally repressed critics in Belarus since claiming reelection in a 2020 vote widely denounced as fraudulent, allowed his country to be a launching point for Putin’s failed attempt to seize Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital. And Putin, while initiating a full-scale war against Ukraine, has cracked down harshly on critics of the war, political opponents, journalists and other dissenters.

After the committee’s announcement, Oleksandra Matvichuk, head of CCL’s board, called for the establishment of an international tribunal to try Putin, Lukashenko and others for their alleged crimes, and decried the failure of international organizations to prevent the war or protect abuse victims.

“Russia should be excluded from the U.N. Security Council for systematic violations of the U.N. Charter,” Matvichuk wrote in a Facebook post. “If we do not want to live in a world where rules are determined by someone with more powerful military potential rather than the rule of law, things must change.”

The Nobel decision was announced as a Ukrainian counteroffensive continued to liberate swaths of territory from months of Russian occupation, revealing further evidence of atrocities allegedly committed by Russian soldiers in Ukraine.

The Nobel committee’s selection of Memorial, which since the 1980s has exposed the crimes of the Soviet gulag and abuses by the Russian state, followed its awarding the Peace Prize last year to Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov, editor in chief of the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta.

Memorial was disbanded this year as Putin cracked down on dissent after the start of the war, and Novaya Gazeta was forced to shut down its operations in Russia. Muratov later auctioned off his prize to benefit Ukrainian children.

The awarding of the peace prize to a Russian group and a Belarusian activist generated immediate criticism in Ukraine, where many politicians and activists view ordinary Russians as complicit in Putin’s war.

“Nobel Committee has an interesting understanding of word ‘peace’ if representatives of two countries that attacked a third one receive @NobelPrize together,” Mykhailo Podolyak, an adviser to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, said on Twitter. “Neither Russian nor Belarusian organizations were able to organize resistance to the war. This year’s Nobel is ‘awesome.’ ”

Masi Nayyem, a prominent Ukrainian lawyer and activist, said his compatriots were paying a high price to defend their values, which he said were “significantly different from the values of Belarusians and Russians who give silent consent to those war crimes and atrocities that are happening in Ukraine.”

The Nobel Committee, in explaining its award, called on Belarus to free Bialiatski, who has spoken out against crackdowns by Lukashenko’s government for decades.

Norwegian Nobel Committee Chair Berit Reiss-Andersen said the prize was for people and entities and not directed against Putin, who turned 70 Friday, nor against anyone else.

“The attention that Mr. Putin has drawn on himself that is relevant in this context is the way civil society and human rights advocates are being suppressed,” Reiss-Andersen told reporters in Oslo.

Belarusian opposition figures hailed the award, calling for the release of political prisoners. Exiled opposition leader Svetlana Tikhanovskaya described it as “an important recognition for all Belarusians fighting for freedom and democracy.”

In a statement, President Biden congratulated the winners, who he said had distinguished themselves by “speaking out, standing up, and staying the course while being threatened by those who seek their silence.”

The prize, set up by the will of Swedish businessman and inventor Alfred Nobel in 1895, is a gold medal and an award of $1.14 million. Unlike the other prizes for physics, medicine and other disciplines, which are selected and awarded in Sweden, Nobel chose a Norwegian committee, selected by that country’s parliament, to administer the peace prize.

The award is valuable international recognition for Memorial, Russia’s oldest human rights organization, which has come under intense pressure from Putin’s government in recent years as part of a clampdown on civil activists and rights groups that accelerated last year ahead of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February.

The International Memorial Society is renowned for researching and memorializing the Soviet-era executions and imprisonment of dissidents. Its human rights wing, Memorial Human Rights Center, exposes the current abuses by Russian authorities and played a leading role in revealing military atrocities during the two Chechen wars in the mid-1990s and early 2000s.

The group publishes a list of political prisoners in Russia and maintains a large archive on human rights abuses by Russia’s security services going back to Soviet times.

Last year, Russian courts abolished both wings of Memorial after earlier declaring them “foreign agents,” ordering the organization to disband in a move that shocked global rights advocates and observers of Russia.

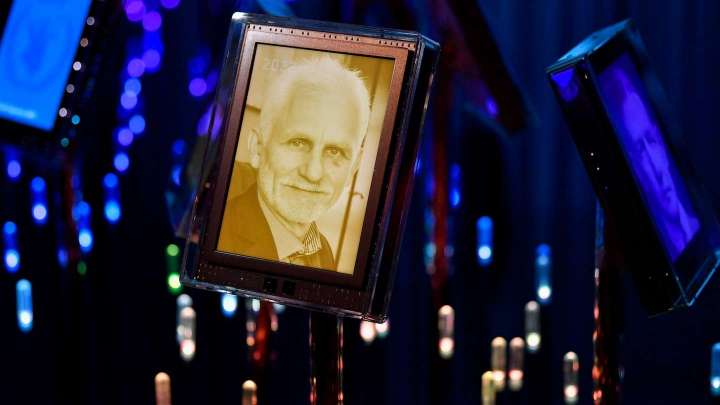

In a parallel effort in Belarus, Bialiatski founded the Viasna center in 1996 to track cases of persecution of activists and document torture and abuse of political prisoners by Belarusian security forces.

Bialiatski was first arrested in 2011 and spent three years behind bars on tax evasion charges that he and his supporters viewed as direct retaliation for the activities of Viasna, which was instrumental in helping Belarusian civil society keep track of the biggest crackdown in the country’s modern history after the protests of 2020.

Tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets in August 2020 to decry Lukashenko’s declared victory in what is widely seen as a rigged election that allowed the longtime leader a sixth consecutive term. The hunt for demonstrators launched by Lukashenko in retaliation triggered an exodus from the country. Still, thousands have been detained and in some cases tortured and beaten in prisons.

At least seven Viasna activists, including Bialiatski, were arrested last year. Bialiatski was accused of tax evasion, as he had been previously, a charge he denies.

In Ukraine, CCL as part of its “Euromaidan SOS” initiative documented and publicized abuses that occurred during a wave of anti-government protests in 2013 and 2014. Since then, the initiative has focused on events related to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its backing of separatists in the eastern Donbas region of Ukraine. The group also has created a map of forced disappearances across Ukraine.

Last month, Matvichuk and the CCL received the Right Livelihood award, known as the Alternative Nobel, for “building sustainable democratic institutions in Ukraine and modeling a path to international accountability for war crimes.”

Oleksandra Romantsova, another CCL official, said the prize sent a needed warning to the Russian government over rights violations and the defiance of international norms, not just in Ukraine but in places like Moldova, where hundreds of Russian troops are stationed inside its internationally recognized borders, and in Syria, where Kremlin support has played a key role in permitting Damascus to violently stamp out opposition.

“If we don’t stop it here now, they’ll be growing, and take more and more territory and take more and more places where people will be suffering,” Romantsova said in a voice message.

Ryan and Khudov reported from Kyiv. Dixon and Ilyushina reported from Riga, Latvia. Ellen Francis and Paul Schemm in London, William Branigin in Washington, Isabelle Khurshudyan in Kryvyi Rih, Ukraine, and Natalia Abbakumova in Riga contributed to this report.