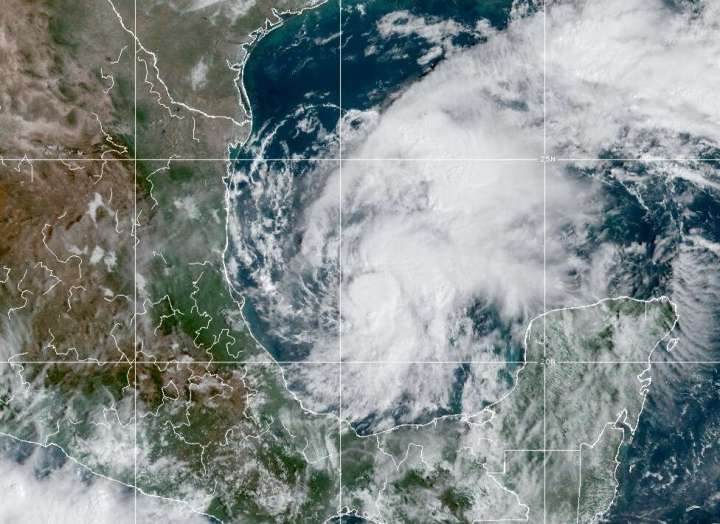

If it seems like Tropical Storm Karl developed virtually overnight, that’s because it did. On Monday, the National Hurricane Center estimated that a disorganized area of showers and thunderstorms in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico had a mere 10 percent likelihood of becoming a named storm. By Tuesday evening, it was Karl.

Tropical Storm Karl develops in Bay of Campeche, set to drench Mexico

Now tropical storm watches are in effect from Tuxpan to Frontera along Mexico’s east coast, where gusty winds and drenching rains are expected later in the week. A few rainfall totals could approach a foot, which the National Hurricane Center warns could bring “flash flooding with mudslides in higher terrain.”

Rough surf is anticipated, too, with rip currents a threat along area beaches. The storm is projected to make landfall between Friday night and Saturday morning, although gusty downpours could begin to move ashore Thursday.

While Karl isn’t expected to pose a problem for the Lower 48, it is one more name off the World Meteorological Organization’s 2022 naming list for the Atlantic. Despite the recent uptick in activity, the season is still about 20 percent behind average, defying widespread calls for a busy season.

As a yardstick for overall seasonal hurricane activity, meteorologists rely on a metric known as ACE, or Accumulated Cyclone Energy — which takes into consideration storm intensity and duration. Thus far, storms this season have expended 82.2 ACE units on their strong winds, compared with a season-to-date average closer to 103.6 units. ACE is proportional to the square of wind speed, meaning stronger storms are weighted exponentially more than their weaker counterparts.

Approximately half of this season’s ACE was burned through by just two storms — Ian and Fiona, the latter of which spent roughly four days as a high-end Category 3 or Category 4 behemoth before slamming into Nova Scotia.

From the standpoint of the expected number of storms through Oct. 12 based on historical averages, this season is actually tracking very close to normal. To this point, we’ve seen 11 named storms, five hurricanes and two major hurricanes, compared to averages of 12, five and two, respectively.

As of 10 a.m. Central time, Karl was centered about 200 miles north-northeast of Veracruz, Mexico. Karl was crawling northward at 3 mph, with maximum sustained winds of around 45 mph.

About 4 a.m. Central time, a NOAA buoy northeast of Karl’s center reported sustained winds of 38 mph — just 1 mph shy of tropical storm force — and a gust to 42 mph. That bolsters confidence that sustained winds exceeding the 39 mph threshold are certainly present somewhere within Karl’s inner core.

Tropical storm-force winds extend outward a little more than 100 miles from Karl’s center, making it a rather large storm, though it’s not particularly intense.

On satellite imagery, it appeared that much of Karl’s inclement weather was focused east of the center. The darker red and white hues on infrared satellite represent extremely cold, and therefore tall, cloud tops.

Where Karl is going

Karl has nearly plateaued in intensity, and should remain a run-of-the-mill tropical storm for the next day or so. It will slowly drift to the west or west-southwest Wednesday before curving more toward the south-southwest Thursday.

An eventual landfall is likely Thursday in Veracruz. Gusty winds to 45 or 50 mph and a minor ocean surge, combined with hazardous rip currents, will exist as secondary hazards — the primary concern is heavy flooding rain.

The National Hurricane Center is forecasting a broad 3 to 7 inches, with localized 12-inch totals in Veracruz and Tabasco.

An unusual formation process

An important feature in how flow is modulated in the Bay of Campeche is the occurrence of a Barrier Jet that results in enhanced low-level northerly flow parallel to the Sierra Madre mountains.

Background easterly low-level flow is blocked by mountains & turned southward. pic.twitter.com/WConhQDhTe

— Philippe Papin (@pppapin) October 12, 2022

Karl came about in a rather circuitous way; it was essentially planted by leftover convection, or a piece of pinched-off thunderstorm activity, from since-disintegrated Julia. Julia made landfall as a Category 1 hurricane in Nicaragua on Sunday, gradually weakening as it hopped the continental divide and curved northwestward in the Pacific — though its broad envelope of storminess spanned hundreds of miles.

That cluster of remnant thunderstorms took on a life of its own, capitalizing on warm ocean waters and blossoming in the wake of favorably weak upper-level winds. The Bay of Campeche’s bowllike shape probably enhanced the consolidation of vorticity, or spin, and hastened Karl’s formation.

Philippe Papin, a specialist at NOAA’s National Hurricane Center, also noted that a “barrier jet” setup may have contributed to Karl’s maturation. North-northwesterly winds funneling down the Sierra Madre Mountains helped “close off” Karl’s circulation — essentially providing the “wraparound” of wind needed to complete a full spiral of wind. Generation of a closed low-level center is integral to tropical cyclone formation; once a near-surface vortex is established, thunderstorm updrafts can vertically stretch it, and a tropical storm can quickly assemble around it.