Why is America playing games with Japan instead of selling them?

OPINION:

Even America’s best allies don’t always play fair when it comes to international trade. Take Japan. It’s one of our most important economic partners yet, year over year, the trade imbalance between our nations runs into the billions.

To put it bluntly, the Japanese have not done enough to open their markets to U.S.-made goods. Thanks to the previous administration’s tough talk on trade, things are better than they once were, but there’s still a long way to go.

Americans generally believe in free trade. That’s part of the reason Sony’s PlayStation platform has captured more than half – 59% – of what the U.S. Federal Trade Commission calls the “high-end gaming console” market. The Japanese, on the other hand, don’t. Their industrial policies favor goods made by Japanese companies, a sentiment many on this side of the Pacific refer to as “cultural protectionism.”

It’s not fair and may not even be legal according to existing trade pacts, but it’s why Microsoft, whose Xbox platform is the No. 3 gaming console in the global market, accounts for less than 4% of the market in Japan.

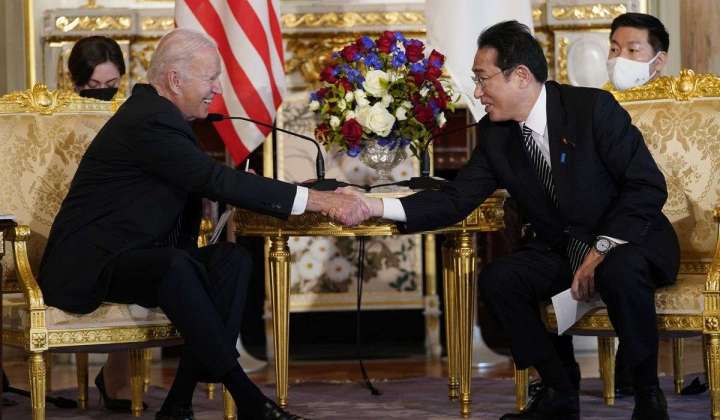

The U.S. government should be swinging the big stick to open markets further so American companies can not only be competitive in global markets but can, where possible, lead them. One place where this can happen is in the video gaming space — but it won’t as long as the Biden administration, and the Japanese continue to make common cause in the effort to block Microsoft’s proposed acquisition of Activision-Blizzard, the company behind the incredibly successful Call of Duty franchise.

Sony’s also pressuring regulators in other countries. It was recently reported, for example, that it is also urging antitrust officials in the United Kingdom to put a collective thumb on the deal, valued at $69 billion, or force the sale of “Call of Duty” to prevent potential harm to consumers in the cloud gaming and console markets.

You might think U.S. regulators and the Trade Rep would be for the deal on its merits. It’s good for the industry, would increase competition, and probably lead to a reduction in costs for consumers. These are all things antitrust regulators are supposed to encourage, not block.

Microsoft is an American company, and what’s good for American business is supposed to be good for America – until you consider the recent leaks suggesting FTC Chairman Lina Khan and others involved in trade policy and trade regulation have been pushing foreign regulatory bodies to get tougher on U.S. companies. She and the other senior government officials involved apparently have their priorities out of whack.

Sony reportedly maintains its dominance in the Japanese market by paying publishers not to distribute their games on both the Xbox platform and the Xbox subscription service. Underhanded, possibly illegal tactics such as these have given it near monopoly status yet the Japanese Fair Trade Commission spends its time aggressively investigating potential antitrust violations by American companies or slow walks required approvals, such as the proposed acquisition of Activision-Blizzard.

The disparity in access to the gaming market is clear. Sony is engaged in anticompetitive behaviors that effectively shut Microsoft out and it’s the responsibility of the U.S. Trade Rep to do something about it. The FTC, unsurprisingly, since Chairman Khan seems to believe that bigger is badder, at least for an American company, has gone along.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Congress, which should recognize how vital the U.S. high-tech industry is to job creation and economic growth, could start asking pointed questions, such as why during her tenure Chairman Khan has allowed antitrust law to be turned on its head.

America voted for President Biden, believing he was the friend of the working man. His trade and regulatory policies have many of us now questioning that assumption. The unfair practices used by the Japanese to protect its share of the gaming market from U.S. competition should not be tolerated. No one needs to start a trade war to get these issues resolved. There are plenty of other ways to handle it, but only if the senior American officials’ riding point on these issues start bringing it up.