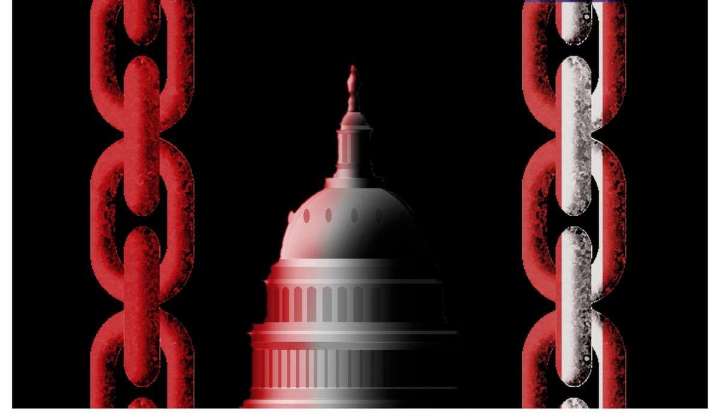

Weakening U.S. trade protections cements Chinese supply chains

OPINION:

Recent op-eds from the heads of tech industry groups and their Washington lobbyists have decried the U.S. International Trade Commission for doing its job — stopping products that infringe on U.S. patents from entering the country.

Big Tech talking heads view this as nothing less than a full-fledged assault on American innovation. But their “solution” would keep their supply chains firmly in China’s hands while working against U.S.-based manufacturing.

The problem, they claim, isn’t patent-infringing products flooding the U.S. market from overseas. Instead, they’d have you believe the problem is “patent trolls,” a trope the tech industry fabricated to dehumanize patent owners who dare to assert their international property rights.

Indeed, the “patent troll” is the monstrous and largely imagined opponent against which these firms have waged an anti-patent war for nearly two decades. The infringers’ lobby wants people to believe that the “trolls” are gaming the ITC, “twisting the Commission’s rules” to “extort legitimate businesses” that import products they manufacture overseas.

It’s an outright exercise in spin and a gross betrayal of the facts.

First, there’s the matter of “patent trolls” — the pejorative term for nonpracticing entities, or NPEs — and the scope of their role in ITC investigations. Here, as has been the case with assertions about patent litigation, a great deal of hyperbole portrays NPEs as the driving force behind ITC exclusion orders that “target small-business innovators” and threaten to “kill the Apple Watch.” The claim is a combination of linguistic gymnastics and creative accounting.

The point behind all this posturing is to promote a venal piece of legislation ironically named the “Advancing America’s Interest Act,” or AAIA. Rather than protect America’s interests, the bill would further erode domestic manufacturing and undermine the patent system that has underpinned American innovation since our founding.

As you might suspect, the vast majority of ITC investigations — nearly 80% of cases — involve infringing products coming from China. By making it more difficult for U.S. patent owners to assert their intellectual property rights against these imports, the bill would incentivize U.S. businesses that want to sidestep licensing fees to manufacture infringing products overseas — all but ensuring that our high-tech supply chains remain dominated by China. And if U.S.-based firms could do it, Chinese firms would likely follow suit.

The AAIA might be more appropriately named the “Made in China Act.” It would gut IP protections to China’s clear benefit and to the detriment not only of American patent owners but also American manufacturing and American workers.

This measure would first narrow the scope of remedies available under Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, the law that grants ITC its power. It would limit Section 337 remedies to a license “that leads to the adoption and development of articles that incorporate” the intellectual property. Thus, the bill would let infringers that have already imported the patent-infringing product into the U.S. off the hook. This would create a perverse incentive for firms of whatever nationality to speed the delivery of infringing products to the United States to defeat 337 claims in advance.

Second, it would raise the bar on who could seek an exclusion order. The bill would require that those having a license to intellectual property must join the patent owner as a co-complainant. That would saddle patent owners with having to persuade licensees to take on the financial burden and the risk of alienating other companies by being party to an investigation.

Universities, research laboratories and small businesses focused on innovating rather than manufacturing would all be subject to this restriction, whose clear purpose is to make it harder to stop infringing products from coming in from overseas.

In truth, the bill is a solution in search of a problem. While the number of ITC investigations sought by NPEs increased in 2022, the total number remains small at 19 in 2022, less than two per month, compared with the millions of technology products that are imported every day.

Big Tech companies would no doubt prefer not to pay licensing fees and avoid the inconvenience of investigations into the foreign-made products they import. But the action the AAIA proposes would impose legal hurdles so high that the ITC’s exclusion order power would be gutted, except when exercised on behalf of Big Tech against foreign competitors.

For Big Tech, the AAIA would be a great victory, but for leading innovators, research institutions, small inventors and the American innovation ecosystem, it would be a heavy blow. And it would cement manufacturing and supply chains in China and other foreign countries.

• James Edwards is executive director of Conservatives for Property Rights (@4PropertyRights) and patent policy adviser for the Eagle Forum Education & Legal Defense Fund. The views expressed here are solely those of the author.