A new approach to saving the old homes of Seoul

SEOUL | South Korea boasts thousands of years of history, but save for a few signature, heavily-restored sites like medieval palaces, tourists in Seoul have to dig deep to discover the capital’s architectural heritage.

Within living memory, the bulk of the city’s population lived in hanok, or traditional homes. These single-story, wood-framed, thatch- or tile-roofed cottages lined picturesque lanes, or golmok, granting Olde Seoul a timeless, uniquely Korean quality.

With much of the millennial, wealthy, wired capital now an international “Everycity,” that quality is gone.

Some districts were smashed in street fighting during the Korean War in 1950, but many were untouched. But the real architectural game-changer was post-war development.

As South Korea swiftly industrialized in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, rural dwellers flooded Seoul for work and vast swaths of old homes were bulldozed to make space for modern infrastructure. Population density necessitated endless blocks of high-rise apartments — convenient and comfortable, but aesthetically barren — which now dominate the cityscape.

The second wave of destruction — one that continues to this day — was sparked by democratization in 1987. Land owners vocally protested for their right to develop, even in areas noted for concentrations of hanok housing. The motive was profit: multi-story buildings are more remunerative for landlords.

While Seoul has preserved and updated monumental architecture — royal palaces and Buddhist temples — the heritage of ordinary citizens has been virtually obliterated, and Seoul’s historic hanok today teeter on the brink of extinction.

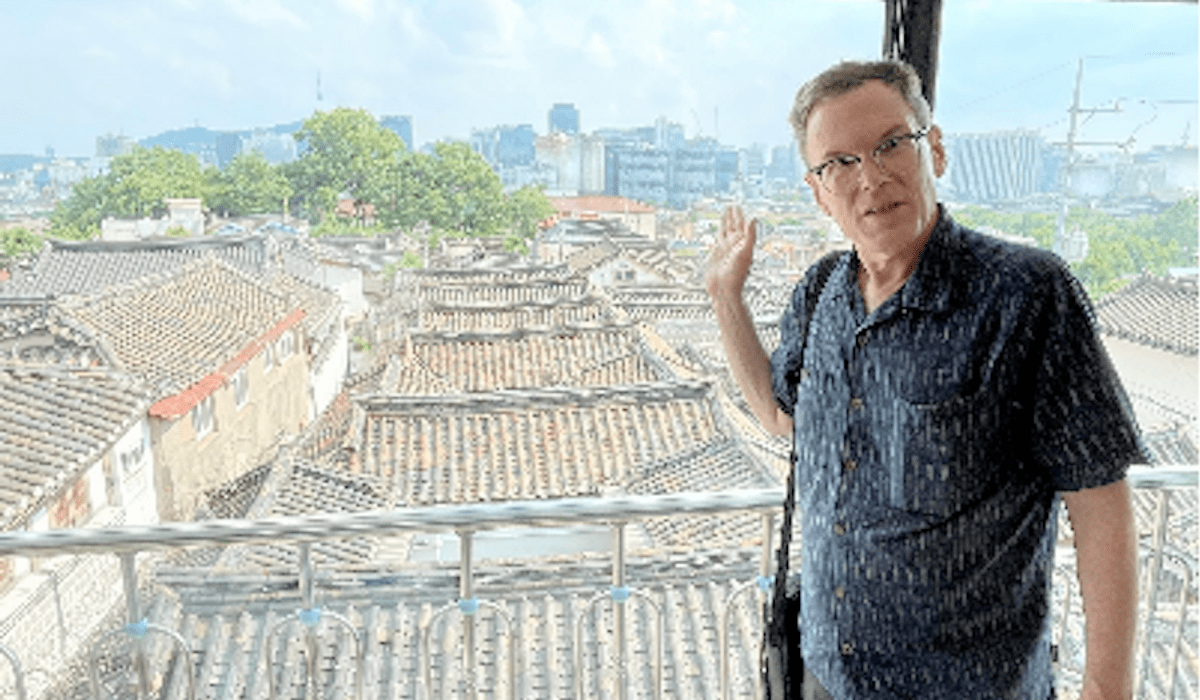

Into this vortex has stepped American Robert Fouser.

“Unless the real estate development mechanism loses power, it will keep building — which means destroying everything in its way,” Mr. Fouser said. “Seoul is going to end up a generic concrete jungle with no connection to Korean heritage or tradition.”

However, he sees hope in the rising generation of young South Koreans, a newfound appreciation of the country’s heritage, and in nascent changes to long-held investment practices.

American champion of Korean cottages

Mr. Fouser, 61, is an author and academic who divides his time between his home base in Rhode Island and stays in Japan and South Korea. His love for traditional Asian architecture was in the family.

“My father was in the U.S. occupation army in Japan,” he recalls. “He had studied draftsmanship, so was sent to Kyoto to do architectural drawings.”

Mr. Fouser’s father introduced Asian elements to his U.S. home and told many a tale of the buildings and sights he witnessed while in Asia. It rubbed off.

Mr. Fouser himself spent a year in Japan as a high school exchange student. He then took degrees at the University of Michigan and Trinity College, Dublin and relocated to Asia, eventually spending 29 years overseas.

He has lived in three different hanok and published five books in Korean. A pending work, covering architectural preservation benchmarks in Europe and the U.S., is set for publication late this year.

He delivers hanok lectures, offers tours and writes columns in leading popular media — he has even led visiting British royalty down little-known golmok.

He is following a lead set by the late Englishman David Kilburn, who died in 2019 and the late American Peter Bartholomew, who passed away two years later. In a country where — unlike the West — celebrity endorsements of issues are not customary, the three expatriates, with their passion for hanok, won a large and respectful following here.

“We also believed in the values of our own traditions, so listening to them was confirmation,” recalled Hwang Doo-jin, one of South Korea’s leading boutique architects, and a friend of Mr. Fouser. “But they were these very educated gentlemen from the West, so that was a different kind of confirmation.”

Mr. Fouser’s predecessors were diehard restorationists, demanding utmost historical authenticity.

Both despised the practice of deploying City Hall funds to destroy frail old hanok and raise new hanok in their place. That practice changed the face of Bukchon, Seoul’s most famous — but now hardly historic — hanok quarter.

Neo-hanok properties are the new wave. Seoul City announced in February a policy to create 10 “hanok villages” city-wide. These will offer grants to property owners who raise new hanok, or add hanok-style features to existing buildings.in sites across the capital.

This approach may reek of kitsch, but Mr. Fouser is flexible on authenticity. He calls himself a “hanok enthusiast” rather than a “hanok activist” like his predecessors, both of whom suffered injuries at the hands of thuggish property developers as they pursued the preservationist cause.

“Rather than follow the orthodoxy of authenticity and integrity, my line is to preserve or enhance as much of the cityscape as possible,” he said. “If an old house cannot be repaired, I am OK building a new hanok.”

But it is rarely about one home when entire neighborhoods can be on the development chopping block. Powerful, politically connected construction companies buy out locals, then flatten neighborhoods to raise high rises.

Absent top-down change, Mr. Fouser hopes for a bottom-up solution related to accepted investment practices which encourage property owners to develop and redevelop.

“There is no vehicle in Korea for growing your money except property,” he said. “If you really want to preserve hanok and cityscapes, you have to have vibrant capital markets — then real estate could be more of a place to live.”

Speculators and markets

While South Korea is the world’s 10th largest economy, the Korean Stock Exchange, or KSE, is the world’s 15th largest by market capitalization, according to 2023 date from Robust Trader. The KSE is home to mega brands like Samsung Electronics and Hyundai Motor, but lags exchanges in smaller economies such as Switzerland and Australia.

The result: A post-war history of bricks and mortar building emerged for many as the only viable route to wealth.

“The older generation’s entire investments were real estate: They bought homes, and home prices always went up,” said James Kim, a Seoul-based portfolio manager. “Koreans tend to put a lot more weight on real estate than on equities and other financial instruments in other countries.”

But with Seoul property shooting through the roof, change is afoot.

“The young generation is staying away from real estate as it needs a lot of capital,” Mr. Kim said. “They are investing in small-cap equities and [crypto currencies].”

Mr. Fouser hopes that youth, locked out of property markets, will value their hanok heritage differently than their parents and grandparents, who considered them old-fashioned, uncomfortable and unprofitable.

There are encouraging signs. While Bukchon is a city-financed, official preservation district, another Seoul neighborhood getting fresh notice for its hanok stock is not.

In Ikseon Dong, young people have organically preserved hanok. Though many interiors have been gutted and are no longer suitable as homes, they are sustainable, having been converted into chic cafes, bars, restaurants and shops.

Mr. Hwang, whose architectural firm operates a hanok practice, is a fan.

“Architecture changes with time,” he said. “Even old buildings have to find a way to adapt to their new environments.”

“There is a third way between orthodox preservation, and tearing down and building new hanok: That is creative adaptation,” Mr. Fouser added. “This is still destruction, and they are not beautifully restored, but it is better than the alternative, which is raising big towers.”