With the deaths of John Lewis and C.T. Vivian, history seems to be sending a message

Around 1960, Vivian and Lewis were students together in Nashville under the tutelage of the Rev. James M. Lawson, one of history’s great apostles of non-violent political action. Along with Diane Nash, another giant of the campaign for human dignity, they galvanized the Freedom Rides.

Key to Lawson’s greatness was his honesty. He made it fiercely clear to students at his workshops that non-violent black protest would bring out the worst of the Deep South. They would be attacked for sitting down, beaten for marching, murdered for registering black voters. The road to change passed through pain and even martyrdom.

Lewis and Vivian graduated from Lawson’s school on different, complementary paths. Vivian became one of the great preachers of his — or any — generation, his oratory greatly admired by no less an authority than the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Vivian’s non-violent protests landed him in the hellhole of Mississippi’s Parchman Farm, the ghastly state prison from which he emerged with his vast dignity and integrity entirely intact.

Lewis’s eloquence was more physical, more visceral. He left the Nashville training ready to die for civil rights. Not in some theoretical sense: ready to die today, die tomorrow, die next week — whenever his sacrifice was needed to advance the causes of freedom and love.

In Alabama, Lewis was beaten nearly to death at a Montgomery bus station, smashed in the head with a wooden Coca-Cola crate. He was beaten nearly to death on a bridge in Selma. The world saw his grandeur on the evening news. His self-possessed suffering made fools and monsters of his foes.

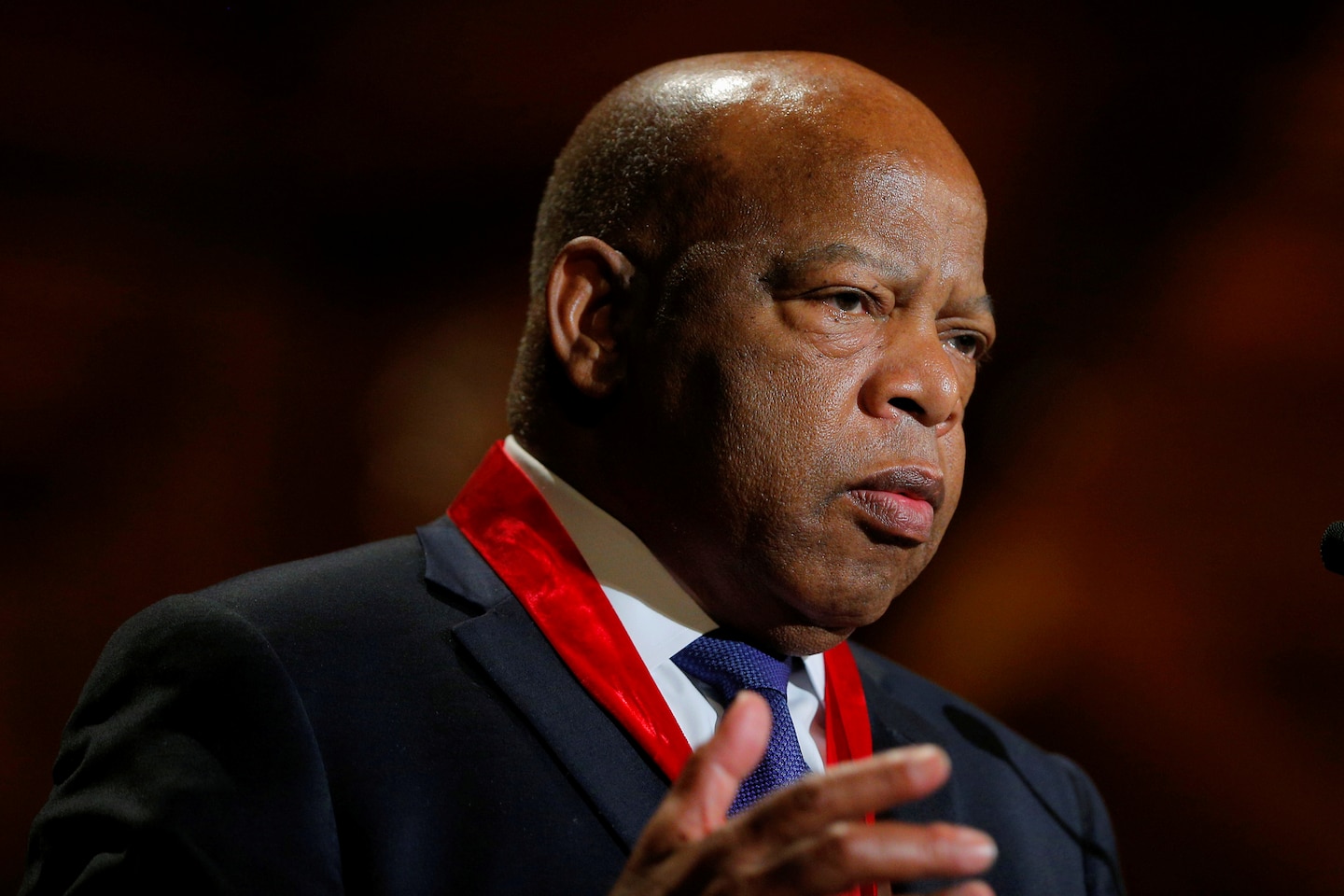

Later in life, as a member of Congress from Georgia, Lewis proudly wore a starkly bald head that compelled respect like a carved idol. The bones of his skull were on frank display. Which ones took the brunt of that crate swung ferociously at the bus station in Montgomery? Where did the club land that knocked him unconscious as he marched with King in Selma across the Edmund Pettus Bridge?

Over the years, in Washington and elsewhere, I’ll admit I studied that battered skull. Notebook in hand, I couldn’t look at Lewis without imagining the pain. When I finally had the chance, I asked him how he steeled himself for such suffering — “How do you prepare mentally and spiritually to be non-violent in response to what you know is going to be a violent attack?”

Lewis replied in the simple, gentle — always authoritative — tones that were his hallmark. His voice, as old and soft as anthracite, invited agreement, and made it impossible to disagree in good faith.

“You studied the way of peace. You studied the way of love,” he answered. “You studied the philosophy and the discipline of non-violence. We had been taught” — by Lawson and King and by each other in the school of non-violence — “never to hate or become bitter, never to lose the sense of hope. And in the process, you may get arrested a few times. You may be beaten and left bloody, left unconscious. In Montgomery, I was hit in the head with a wooden crate, and in Selma, I had a concussion on that bridge. I saw death: I thought I was going to die.

“But you keep going. You see something that is so necessary, so right. And I say to my colleagues sometimes, and to friends in my district, and to brothers and sisters in the movement, that you have to be hopeful, you have to be optimistic, be hopeful, keep going!

“Don’t get lost in a sea of despair.”

Sometimes history tries to send us a message. And this unsettling, turbulent period of ours seems to invite an intervention. Maybe history is saying this: Two of our best, two giants, two heroes, two voices, two glories of peaceful persuasion, of victory without violence, have left the stage arm-in-arm, fists raised in triumph. Take their message to heart. Ours is not the first discouraging moment. Can we resolve, like them, not to falter into despair?

Read more: