‘Invictus’ was among John Lewis’s favorite poems. It captures his indomitable spirit.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Could the boy reciting those lines have imagined that he would famously endure vicious beatings by white supremacists? That he would survive, and go on to serve more than three decades in Congress?

Lewis, who died Friday at age 80, was one of 10 children raised by sharecropper parents in Pike County, Ala. As I have learned while working on his biography, Lewis always loved to read — comic books, the Bible and, as a teenager, the Montgomery Advertiser. In its pages he absorbed the thrilling news in 1955 of the Montgomery bus boycott and its 26-year-old leader and apostle of nonviolence, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

It was with the goal of becoming a minister like King that Lewis enrolled in the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville in 1957. But he soon grew enamored of the Social Gospel, with its goal of bringing liberal Christian teachings to bear on the world, and sought out the nascent civil rights movement.

Within a year, he was learning from the Rev. James M. Lawson, who had studied in India and was leading student workshops in Nashville in nonviolent direct action. Like King, Lawson spoke of working to achieve “the Beloved Community” — an inclusive, multiracial view of God’s kingdom on earth.

In an era of protests, the Nashville activists were notably successful. Just months after their first sit-ins in February 1960, Mayor Ben West agreed to desegregate department-store lunch counters, making the city the first in the South to do so. When activists around the South formed the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee that April, the Nashville Student Movement, and Lewis, were at its heart.

The following year, the Congress of Racial Equality called for black volunteers to ride Greyhound buses across the South — challenging states to enforce a Supreme Court decision mandating racially integrated travel. The 21-year-old Lewis quickly signed on as a Freedom Rider.

National television news crews followed the riders as they traveled from from city to city, letting Americans witness successive acts of white supremacist brutality. At the Rock Hill, S.C., bus terminal, Lewis entered a “whites only” waiting room, and racists punched and kicked him until he tasted blood. In Montgomery, Ala., racist thugs knocked him unconscious with a Coca-Cola crate.

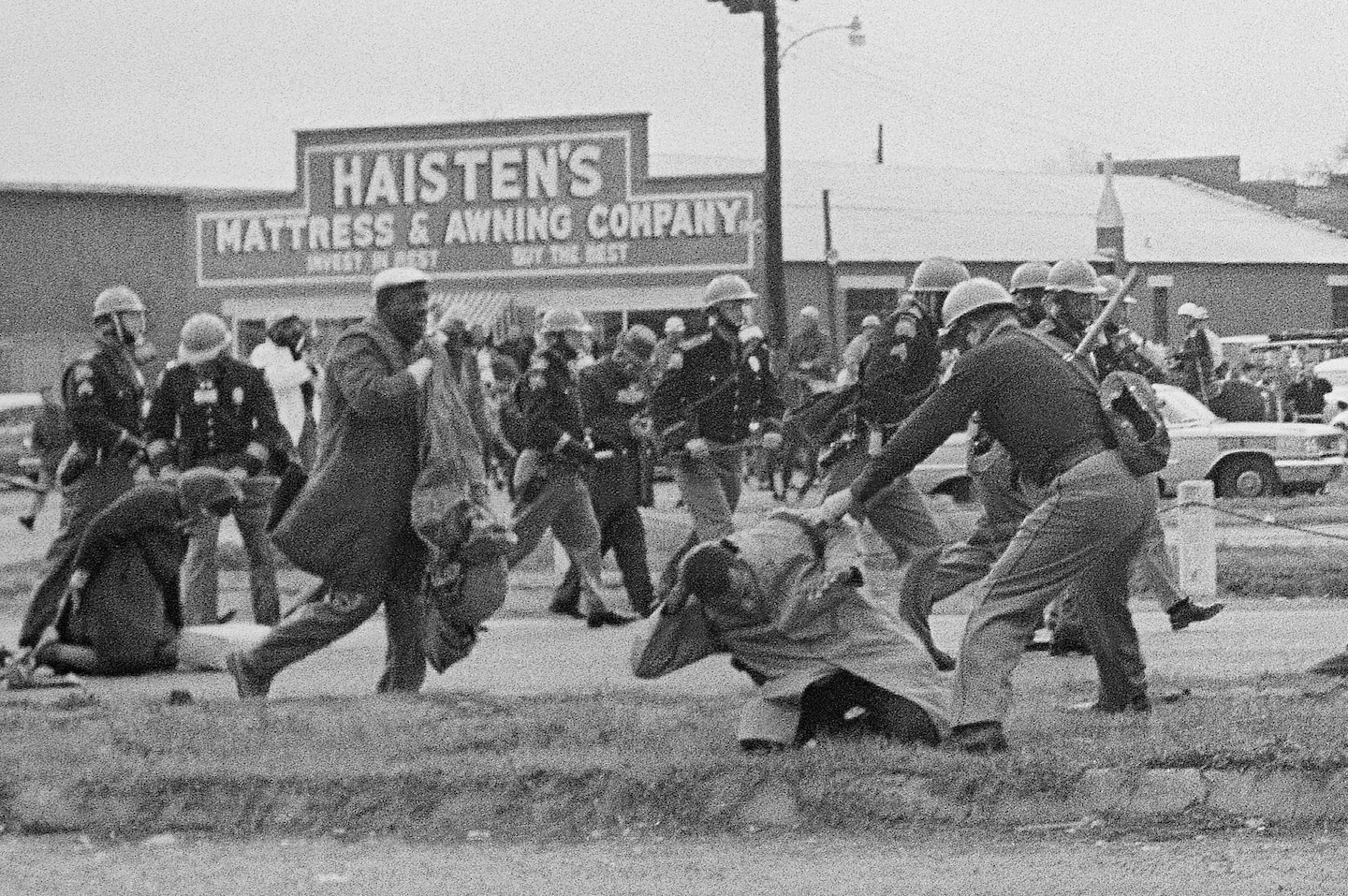

In 1963, at 23, Lewis became SNCC chairman and spoke that summer before 250,000 at the March on Washington. In 1965, he was a leader of the march at Selma on what became known as “Bloody Sunday”; state troopers clubbed him with their truncheons, fracturing his skull.

The sheer physical courage Lewis displayed time and again, refusing to respond in kind, made him a hero of the movement. But the political climate was changing fast. Just after being reelected chairman of SNCC in 1966, he faced a rebellion: Opponents charged him with being too keen to partner with President Lyndon Johnson’s White House; too close to King; too supportive of interracial alliances and out of step with the increasingly militant tenor of the times. On a second vote, of dubious legality, the group elected a new chairman, Stokely Carmichael, who launched the ultimately divisive philosophy of “Black Power.”

So Lewis went to New York and took a job with the Field Foundation, which underwrote civil rights activism. There he came under the influence of Bayard Rustin, who believed that “interracial democracy” allying black and white activists was both a practical and moral imperative, and that elective politics would provide the path for black progress.

Lewis came to agree. In 1968, Lewis joined Robert F. Kennedy’s comet-like presidential campaign, which ended cruelly with the senator’s assassination in June. For much of the 1970s, Lewis ran the Voter Education Project, which organized Southern blacks to claim their right to the franchise. Finally, Lewis chose to run for office himself, at first unsuccessfully, but in 1986 winning a Georgia seat in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In his more than three decades in Congress, Lewis fought to preserve and build on the gains of the civil rights movement. He backed legislation to renew and expand the Voting Rights Act and was a prime mover behind the establishment of the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the Mall in Washington.

In December 2019, Lewis learned he had Stage 4 pancreatic cancer. He battled the illness with the same equanimity with which he had braved beatings and arrests as a Freedom Rider.

Last May, in a phone interview, I asked Lewis about the poem “Invictus.” He laughed and said that his staff members knew it was a favorite of his, and teased him about it. The poem, it was clear, captured John Lewis’s indomitable spirit.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.

Read more: