The Trailer: What we know about how this election will work

What do we know about the actual conduct of the election? Plenty, though probably not enough to make anyone comfortable, and there are months left for candidates to file lawsuits, or even climb onto the ballot.

When will we know who won? It’s complicated. If there’s a decisive result, we may know who’s winning, but not the final numbers, late on election night. If it’s close, the results in the key states might not be known until a week later, or more. And that would be true of the presidential election, as well as the downballot races that will determine control of Congress.

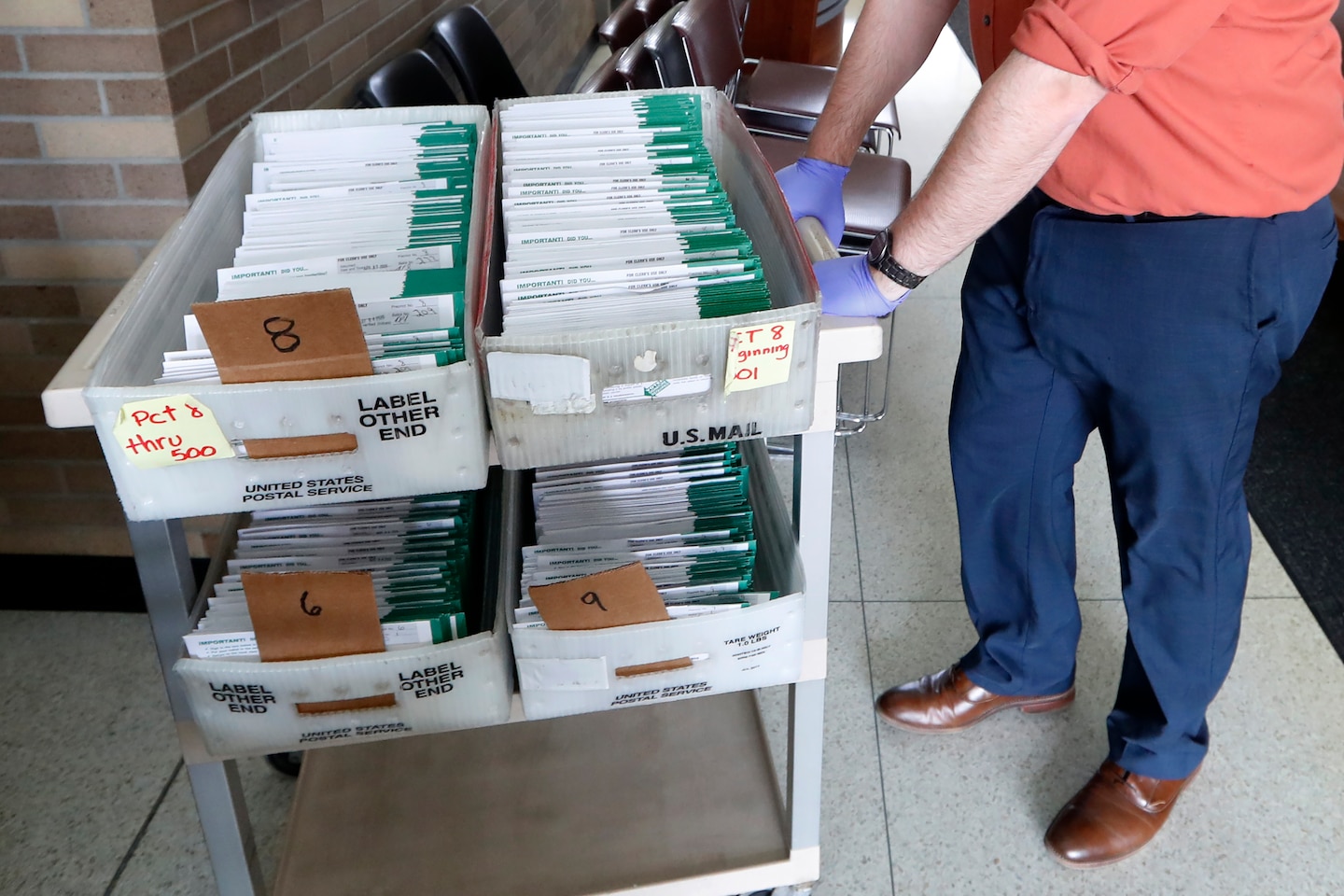

Here’s the thing: We never have every single vote counted on election night. The results that candidates and media rely on to declare winners are tabulated when precincts report their votes. That’s subject to human error, and it’s not unusual to see swings in reported numbers if, for example, a clerk accidentally adds a digit to the end of the numbers they’re reporting. That counting and reporting can be even slower in states where a substantial number of people vote by mail; in some states, the ballot must get to officials on Election Day, while in others, it just has to be postmarked by then.

Counting is a laborious process, but some states handle it more quickly, beginning to process and count the first ballots received before Election Day is over. The process involves verifying signatures, so that voters who’ve sent ballots in can check online to see whether their votes were counted, and “cure,” or fix, the ballots if they weren’t.

If the entire country operated like Colorado, where all votes are cast by mail and must be received by Election Day, there might not be much uncertainty Nov. 3. But most states are ramping up absentee voting in a hurry, and the process has confounded both campaigns and media outlets. Two months ago, the Associated Press mistakenly declared runoffs in two Georgia primaries, not accounting for the huge number of absentee votes. One week ago, the Senate campaign of Texas Democrat Royce West (briefly and incorrectly) projected that it would close a gap with a rival, overestimating how many votes were left in Dallas and Houston.

Our lengthy, disorganized system of state primaries has actually exposed weaknesses in vote-count systems, revealing which states were robust enough to handle the mail ballot glut. New York wasn’t, and tens of thousands of ballots may end up uncounted because Brooklyn post offices did not postmark the ballots coming through.

New York has been an outlier and could easily prevent another mail mix-up by November. Other states’ counts have also been slow, among them decisive battlegrounds of Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, where as in 11 other states, absentee ballots aren’t counted until Election Day.

No primary has seen the sort of turnout that’s expected in November, though typically, more voters sent ballots back quickly in presidential elections than in primaries. In Democratic presidential primaries this year, millions of indecisive voters waited to cast votes until there was some clarity on who was winning. Those who didn’t might have regretted it; a sizable 187,020 Texas Democrats voted for candidates who’d quit before their primary. But in 2016, more than half of Texans voted early in the presidential election, delivering mountains of ballots that were counted quickly.

How to tell who’s winning? By election night, states and counties will have records of how many ballots were requested and how many were received. Imagine an election in which most of Pennsylvania’s votes are in, and the race is tied, but a few rural counties usually won easily by Republicans have yet to report. Imagine another election in which every county’s votes are in, but nothing from deep blue Philadelphia County. You could confidently say who’s got the advantage, if not who has won.

Who gets to vote by mail? Almost everybody, unless you live in one of seven states: Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri and Texas, where Republicans who control the states’ election processes have resisted loosening them for the pandemic. Four other states technically require voters to prove some sort of infirmity to vote by mail but have waived those rules for 2020. In the rest of the country, mail voting is either universal, available to voters without any conditions, or made available to them because of the coronavirus. The map has shifted nearly every week, as legislators and lawyers have taken turns to change the absentee process, at least through the end of 2020. But most of the states that previously required voters to prove that they needed absentee ballots, usually for reasons of age or infirmity, have relaxed those rules.

Judges with lifetime appointments can be unpredictable, but there is no real effort underway to prevent mail voting in the states that have expanded it. While the Republican National Committee has launched a series of voting lawsuits, its attorneys have not tried to limit access to absentee votes; they’ve focused on preventing ballots from being counted if postmarked after Election Day, or disqualifying ballots that lack proper signatures or security forms. (Texas Republicans refused to loosen their absentee law, lost one round in court and defended their law in higher courts.)

In New York, as we saw, human error led to voters who followed the law being disenfranchised. One issue out of states’ control is that the USPS, under the direction of Trump appointee Louis DeJoy, has eliminated overtime and encouraged employees to leave some mail for next-day delivery instead of making extra trips after normal work hours. That will inevitably slow the delivery of some absentee ballots, and slow their return. And the question is whether other states are as ruthless about tossing those ballots as New York has been.

Could legitimate voters be prevented from voting? Yes, and they are in every election. Hundreds of thousands of ballots are tossed out, from mail votes that arrive late, to ballots spoiled by voter error, to provisional votes (ballots filled out by voters who didn’t appear on voting rolls, but can prove their eligibility later), to purging “inactive” voters off the rolls if they don’t return postcards confirming their addresses, which can lead to mass confusion. (Among other reasons, studies have shown the vast majority of voters don’t notice or return the cards.) That was seen in Georgia’s 2018 election, when tens of thousands of voters were caught up in a mass purge, adding to Election Day chaos and leaving some people without ballots.

But the pandemic, which has disrupted so much else about the election, has also complicated the purge campaigns. Wisconsin voters caught a break when the oral arguments about a mass purge were bumped to September, just days before absentee voting will begin, and a month after one of the court’s conservatives will hand over his office keys to liberal judge Jill Karofsky. Judicial Watch, a conservative group that threatens to sue states and counties unless they purge the rolls — even if they’ve removed inactive voters recently, based on their own lists — has met new resistance from county officials who say there simply isn’t a way to pore over this information now. (The argument tends to pit local officials’ data against federal data that has repeatedly found false positives.)

“In the current crises, this is impossible to do on your timetable,” wrote Stuart Wilder, a Bucks County, Pa., solicitor, in a late March letter to Judicial Watch. Something else to consider: Already, the Supreme Court has started rejecting voting rights lawsuits, on the premise that it’s simply too close to the election.

Could the president dispute or overturn election results? If the election doesn’t go his way, it’s possible or even likely that president will dispute the count, or suggest that absentee ballots that run more Democratic than in-person votes — a trend we’ve seen all year — are fraudulent. As recently as this weekend, in calls to voters in tele-town halls, Trump has described “absentee” voting and “vote by mail” as different practices, even though they are not.

But previous Trump complaints about mail voting have gone nowhere. The scenario that Democrats sweat about, the president insisting that late ballots were proof of rigging, actually happened in November 2018. The final waves of absentee ballots broke heavily for Democrat Kyrsten Sinema, giving her the lead in Arizona’s Senate race. “Signatures don’t match!” Trump tweeted “Electoral corruption — Call for a new Election? We must protect our Democracy.” There was no new election, and nothing happened.

Moving the date of the election requires an act of Congress, one that House Democrats aren’t interested in. Asking for recounts requires different thresholds from state to state, from an outright tie (in Texas) to a margin of less than 1 percent (in Nebraska). In a small irony, the Green Party’s quixotic 2016 effort to recount votes in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin led those states to tighten their recount laws; there’s no challenging a Michigan election now if the margin is more than 2,000 votes. Could some lawsuit challenge absentee ballots that were delivered or stamped after the election? Yes. But we are likely to know how those ballots are being handled before Nov. 3.

What does it take to get onto a state’s ballot? In some states, the answer today could be different from the answer tomorrow. There is no federal standard for ballot access, leaving it up to states to determine what candidates need to do to get it. Some states, but not all, have “sore loser” laws that prevent candidates defeated in party primaries from running as an independent or third-party candidate.

Most states have different rules for qualifying entire parties and qualifying individual candidates, sometimes based on a percentage of the votes cast in the last election. One reason the Libertarian and Green parties have had easier times getting on the ballot this cycle, compared with four or eight years ago, is that their presidential candidates did well enough in 2016 to earn a full cycle of automatic ballot access.

So: It’s a mess, and the coronavirus made it messier. That’s what Kanye West is showing (and perhaps discovering) in his haphazard attempt to get on ballots as his Birthday Party’s candidate for president. In a normal year, a third-party candidate would have needed 30,000 valid voter signatures by June 22 to make the ballot in Illinois. But state legislators and attorneys chipped away at that standard, dropping it to 2,500 signatures by the end of business on July 20 — just 0.06 percent of the votes cast in the state’s 2018 midterm elections. It’s unclear whether West made the ballot, as the signatures on the petitions he turned in could be challenged. But surviving a challenge is easier now, thanks to the lower threshold.

Nine states have already closed their ballot lines: Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Texas. The ballot lines in New York and North Carolina aren’t settled yet, but if courts rule against third-party candidates who demand lower signature thresholds, more than 40 percent of American voters will be living in a state where West isn’t on the ballot. Those voters, as discussed above, will have other things to worry about.

Reading list

How the president broke records over a tough political summer.

A bureaucratic backlog that could affect the election.

What it means if Biden wants to break the “concrete ceiling.”

A call for resources to prevent a full Democratic takeover.

What a celebrity known for erratic behavior has in common with some voters in focus groups.

How some senators are reversing their old “let the people decide” position on the court.

Turnout watch

What if they held a primary and nobody came? That was the story in Puerto Rico, more or less, where turnout in its July 12 Democratic primary collapsed more than 90 percent from four years earlier.

“[U]nusually low turnout was predictable due to the voters’ concerns about the continuous spread of COVID-19 in Puerto Rico combined with absence of local legislation providing voters with the option of voting by mail,” Puerto Rico Democratic Party Chairman Charles Rodriguez wrote in an email. “During the past 2 weeks, there has been a spike in COVID-19 cases and an increase in deaths related to the disease. Regardless of the measures adopted by Puerto Rico for the primary, like a strict safety protocol to protect voters, it seems voters were afraid to expose themselves by voting in person.”

According to Puerto Rico Democrats, who tabulated the ballots from the twice-delayed primary, just 6,302 Puerto Ricans voted in the July 12 contest. Joe Biden won 3,930 of them, followed by Bernie Sanders and Mike Bloomberg, who narrowly missed the threshold for delegates. A sizable 275 voters left their ballots blank, while more cast spoiled ballots that could not be counted.

That represented a complete collapse from 2016, when both Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton contested Puerto Rico’s primary, and 88,149 votes were cast. (More votes were cast just for Clinton in the city of San Juan that year than were cast in total this year.) Compared with 2008, the implosion was even more dramatic: 388,477 Puerto Ricans voted in the primary between Clinton and Barack Obama. The punchline: More Democratic presidential candidates stopped in Puerto Rico for campaigning than ever. They just did so when they expected an April primary, not an afterthought election on a hot Sunday in July.

“The other clear reason for the lack of enthusiasm among voters was the public perception that the nomination was already a done deal,” Rodriguez said.

Ad watch

Donald Trump, “Break In.” This is the third Trump campaign ad to portray a future in which a defunded police department is unable to respond to victims of crime. It’s the most visually arresting of the trio, showing an elderly woman distraught at news about police department budgets being cut, then dialing 911 futilely as a masked man enters her home and grabs her. While the audio in the clip has Sean Hannity accusing Biden of wanting to defund police, the ad portrays this as “Joe Biden’s America,” implying that the Democrat has won the election and is in the position to make this real. Still, the message has actually softened as the imagery has gotten starker; the ad, citing Biden’s remarks about redirecting some funds from policing to mental health, says that he would “reduce police funding.” In online messaging, the campaign says flatly that he will “defund” police altogether.

Joe Biden, “Tested.” One of a pair of spots launched this week in battleground states, this answers a problem Biden faced in focus groups: that voters knew him but didn’t know a ton about his record. This focuses on the Obama administration’s stimulus plan and the economic growth that occurred by the end of Biden’s eight years as vice president, with a jobs number of the kind Trump, but for the pandemic, could have been running on.

John James, “Storyteller.” The only black Republican candidate for Senate this year, James has reintroduced himself to voters (he ran in 2018, too) with a lot of biography and no talk of his party. Here, he appears with his father, John Sr., to tell the story of a family that went in four generations from slavery to poverty to prosperity and a Senate bid. “I’m proud to teach my kids that this is the only country where you can go from slave to senator in four generations,” James says.

Protect Freedom PAC, “A Real Deal.” Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky is intervening in Tennessee’s Republican primary for Senate on behalf of Manny Sethi, a conservative physician who has never run for office. The argument, which has circulated in the state as Trump-backed candidate (and former Japan ambassador) Bill Hegarty has struggled: Sethi will be reliably conservative. “Tennessee is too conservative a state to keep sending Democrats in Republican clothing to represent Tennessee,” Paul says.

Majority Forward PAC, “Put Families First.” The Democrats’ Senate super PAC, like the party’s candidates, has yet to find a topic it cannot turn back to health care. A coronavirus-themed ad here focuses on the job Thom Tillis had before the Senate, speaker of the Republican-run state legislature. “When Thom Tillis had the chance to expand Medicaid to get more people health-care coverage, he voted no, leaving half a million North Carolinians without care, families who could really use it right about now,” a narrator says. While the money for expansion has been available for most of a decade, the program is still tied down with Republicans negotiating for more concessions from Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper on how it will be managed.

Poll watch

Do you support reducing funding for police departments to fund social services?

Support: 40%

Oppose: 55%

Do you support renaming military bases named for Confederate generals?

Support: 42%

Oppose: 50%

To the surprise of some critics, who expected civil unrest to backfire on protesters, the aftermath of George Floyd’s killing has moved public opinion against the president. But a few Trump-held positions enjoy majority support. Independents and white voters are resistant to renaming bases such as Fort Bragg, which the president intends to halt by vetoing the National Defense Authorization Act. And the most modest version of “defunding the police,” a redistribution of some law enforcement funding to mental health or anti-abuse programs, is viewed skeptically. (Support for that idea has differed depending on how the question is asked.)

Money watch

ActBlue, the liberal donation portal that has inspired everything from conspiracy theories to a successful Republican analogue, saw $710 million move through its platform in the second quarter of 2018. According to its self-reported data, ActBlue processed more than 18 million donations from more than 5.7 million donors, nearly quadruple the previous quarter. Much of that was because of donations to civil rights organizations, but compared with two years ago, when a surge of donations rattled Republicans then working to defend House and Senate seats, giving to candidates through ActBlue had tripled.

Candidate tracker

Joe Biden rolled out another component of his economic plan this week; ahead of that, he ran a circuit of interviews and fundraisers, including the first episode of Joy Reid’s new MSNBC prime time show.

“I am not committed to naming any but the people I’ve named, and among them there are four black women,” Biden told Reid about potential running mates. “So, that decision is underway right now.”

His plan, introduced in New Castle, Del., was a $775 billion combination of health-care and child-care programs; universal prekindergarten, plus a $5,000 stipend for “informal caregivers.” Like other recent Biden proposals, it combined some ideas that floated through the Democratic primary, adapting from both Elizabeth Warren and Andrew Yang.

President Trump restarted the White House coronavirus briefings that had trailed off at the start of summer, while otherwise embroiled in negotiations over the NDAA, coronavirus relief and immigration. The White House threatened to veto the NDAA unless its rider that would start the process of renaming military bases named for Confederates was struck, while the president wrote a memorandum, contravening the Supreme Court’s recent ruling, asking that noncitizens not be counted in the ongoing census. And the negotiations over what forms of stimulus will be in the “covid 5” package are ongoing.

Countdown

… 14 days until primaries in Arizona, Kansas, Michigan, Missouri and Washington

… 16 days until primaries in Tennessee

… 18 days until primaries in Hawaii

… 21 days until primaries in Connecticut, Minnesota, Vermont and Wisconsin

… 27 days until the Democratic National Convention

… 37 days until the Republican National Convention

… 45 days until some absentee ballots start going out

… 105 days until the general election