Nutrition research has led us astray. Here’s what we should study instead.

Although I’m definitely not lettuce’s biggest fan, today I’m making the case against nutrition research, not salad. Specifically, nutritional epidemiology, where researchers use giant databases to find correlations between what people eat and which diseases they get. Usually, the databases are of individuals, often tracked for many years, but sometimes, and even more uselessly, it’s country-level data.

Sure, it has helped us understand such deficiency diseases as scurvy (not enough vitamin C), goiter (not enough iodine) and pellagra (not enough niacin). More recently, it exposed problems with trans fats. Those undeniably go in the plus column, but we have to weigh those against the minuses. This kind of research is directly responsible for the changing headlines about saturated fat, eggs, carbohydrates, coffee and everything else consumers are confused about. Although I’ll lay some of the blame for that at the media’s feet, plenty of scientists and university PR departments are pumping this stuff out and soliciting that coverage.

There’s a strong case that we have already gotten all the meaningful correlations out of these databases and continuing to look only makes consumers even more confused than they already are. It’s time to move on.

Move on to what? Glad you asked. Because I’ve got some ideas.

Instead of trying to fine-tune our understanding of a healthful diet (eat a wide variety of whole-ish foods), let’s try to bridge the gaping chasm between what we already know to be healthful and what people actually eat.

I’m gonna keep flogging this until morale improves: Diet isn’t a knowing problem, it’s a doing problem. Our environment makes eating healthfully really tough. I’m not talking about cost or access here; they matter, but not as much as the sheer overwhelming ubiquity of tempting food. Let’s help people navigate an environment that derails the healthy intentions of almost everyone.

Here are five ideas.

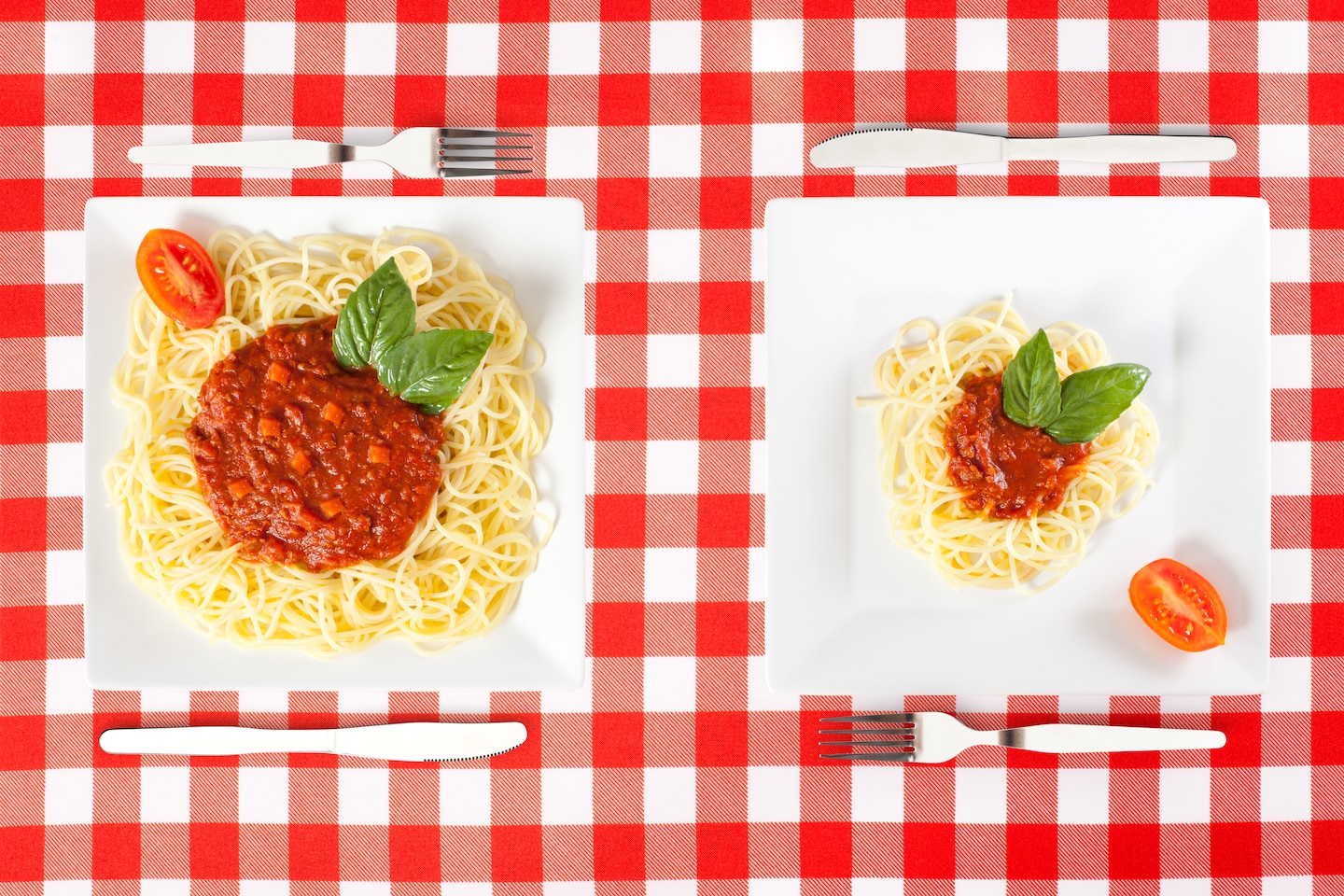

Portion sizes

Muffins weren’t always the size of softballs, and Deborah Cohen, a researcher at Kaiser Permanente, is looking for ways to dial back portion sizes by working with restaurants to include meals on their menus that come in under 700 calories. The recipes don’t change, but dishes from the standard menu are put together in permutations and quantities to keep them under the limit.

As portions got larger, we just got used to it; we have to recalibrate. One 2018 study found that subjects served a small slice of quiche not only ate less than those served a large slice, they took a smaller portion the next day when they were asked to serve themselves. Our sense of portion is malleable, and I would love to see more research on how to adjust it downward.

Food delivery

One way to keep people out of the food environment is to deliver the food environment to them. Cohen is also working on a pilot program that’s like meal kits on steroids — with a food-stamp budget. Participating families will get a delivery of an entire week’s meal plan and the groceries to create it. The point, Cohen told me, is to keep people out of supermarkets, where the temptation is, as well as to answer that pesky “what’s for dinner” question. All nutritional requirements are met, and the food is remarkably inexpensive: Cohen shopped a sample menu for a family of four for a week, and she spent $136.

Of course, participants aren’t required to make the planned meals, but the program makes that option, designed to be healthful, the easy option. If this works, it has a laundry list of advantages: People don’t have to worry about planning, don’t have to travel to the store, have less reason to eat out and may be introduced to new recipes. Yes, please.

Education

When it comes to adults, education has an abysmal track record as an intervention for improving long-term diet quality or losing weight. But could we please teach kids to cook? I talk to a lot of people about changing the food system, and school curriculums are a recurring theme. If kids learn their way around a kitchen and understand the basics of nutrition, they have a fighting chance at forging decent habits. And, please, let’s include school vegetable gardens where climate allows for it. There seems to be at least a possibility that growing vegetables increases the chance that kids will eat them, and there’s not a lot of downside.

Convenience

Pierre Chandon directs the INSEAD Sorbonne University Behavioral Lab in Fontainebleau, France, and studies how the environment influences what we eat. Some of that research involves “nudges,” or small environmental changes that subtly influence people’s choices. In a recent meta-analysis, he found that the most effective changes aren’t things like the plate size or the description of the dish, but things that make it physically easier to choose (it’s closer) or eat (it’s cut up) the more healthful option.

Chandon is studying this in supermarkets, but it’s relevant for any place people make food choices: workplace kitchens, cafeteria lines, buffet tables. According to his analysis, that kind of environmental rejiggering can reduce consumption by 209 calories a day. Would that continue once people got used to the changes? There’s only one way to know.

The simplest manifestation of convenience is proximity, and one 2016 study found that, when snacks were right next to the drink station in an office kitchen, as opposed to a mere 10 feet away, men’s snacking doubled and women’s increased by a third. How much good could we do by simply putting food farther away? I’ve never been convinced that things like small plates and short glasses could have a meaningful impact, but proximity is powerful.

Environmental preferences

As our food environment has become so difficult to navigate that nearly three-quarters of American adults are overweight or obese, I’ve seen almost no research about what people want their environment to look like. Do people want tempting food in their face all the time? One of the few studies I’ve seen about this suggests that they don’t.

Louise Walker and Orla Flannery, at England’s University of Chester, asked people about cake and other sweets in the office and found that 68 percent of them found cake hard to resist, and 59 percent said office snacks made it hard to stick to a diet.

If our environment is our undoing, why aren’t we asking people what they want it to be?

None of these things is easy to study. They take time, and money, and actual human subjects. It’s easier and cheaper to mine the databases. But that’s a version of the streetlight effect, where you try to find things where it’s easiest to look, rather than where those things are most likely to be.

We’ve spent several decades doing most of our looking under the streetlight, and look where it’s got us. It’s time to branch out.