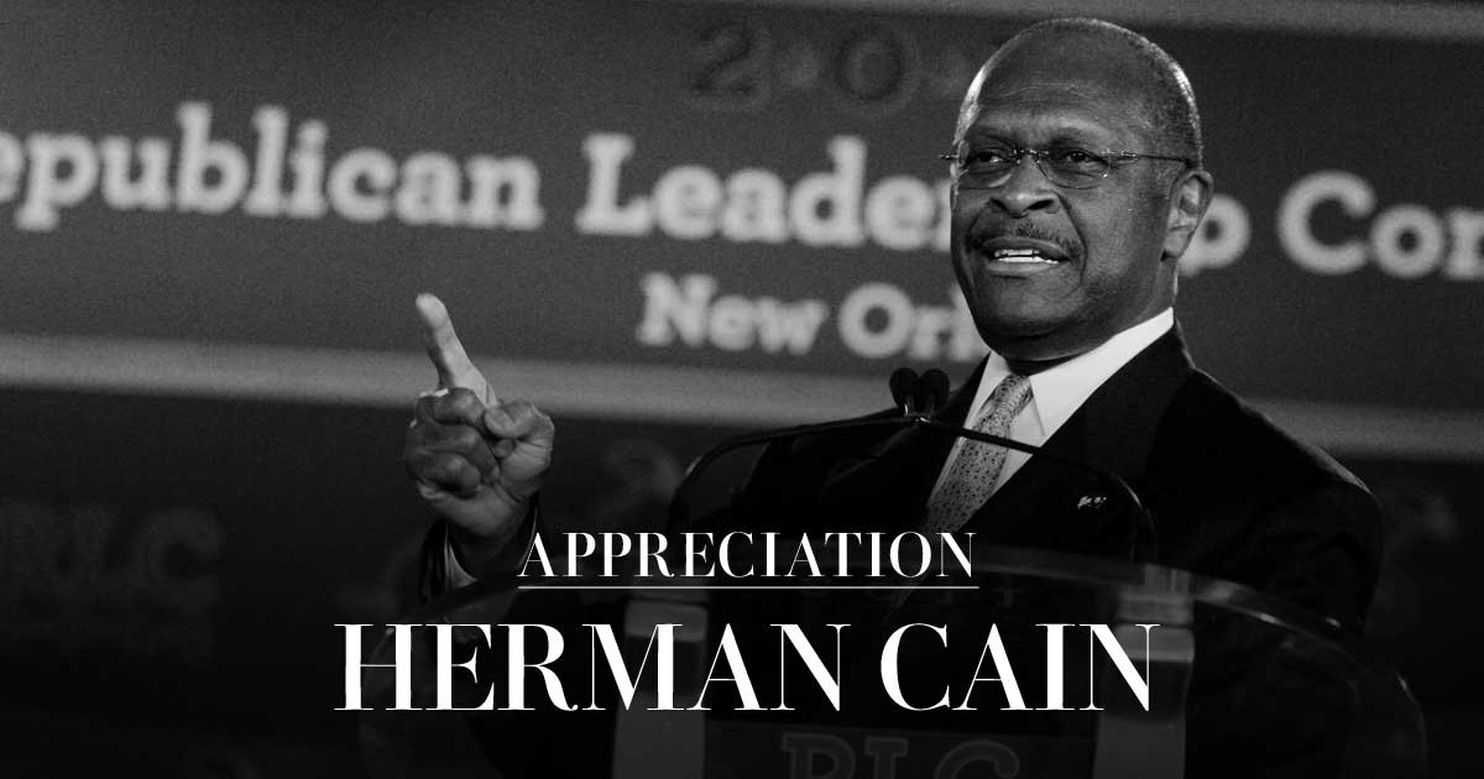

Herman Cain represented the right of Black Americans to intellectual diversity

Herman Cain, a businessman turned politician turned commentator, was a pioneer, a leading member of the bridge generation of African Americans who brought the nation out of legally sanctioned segregation. He also belonged to the much smaller cohort of politically conservative African Americans, lonely ground he shared with such figures as economist Thomas Sowell and Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. In this, Cain represented a civil right sometimes neglected in the national discourse: the right of Black Americans to intellectual diversity.

Cain died on Thursday at an Atlanta-area hospital of complications caused by covid-19. He was 74.

In Cain’s case, the bridge he built led from his father’s version of corporate success to something more like equality. In segregated Atlanta, Black achievement was often measured by the prestige of the people one served. Luther Cain, during the 1960s and early 1970s, served as full-time chauffeur to Robert Woodruff, the head of Coca-Cola and arguably the most powerful man in town.

Driving Woodruff allowed the elder Cain to send his whip-smart son to Morehouse College, the all-male school that — along with its all–female counterpart, Spelman College — educated Atlanta’s Black elite. Cain majored in mathematics, then earned a master of science degree from Purdue University in the cutting-edge field of computers. He graduated in 1971, just as corporate America was half-heartedly integrating.

With the mind of a numbers-cruncher and the personality of a salesman, Cain made the most of the new opportunities. At Pillsbury, in his early 30s, he earned responsibility over some 400 restaurants in the Burger King chain. His focus on service and efficiency boosted the top and bottom lines. In 1986, the food conglomerate charged him with rescuing its floundering Godfather’s Pizza operation.

Cain and a partner later bought the pizza chain from Pillsbury. It was a remarkable achievement for the son of a rich man’s chauffeur from Jim Crow Georgia. Still in his early 40s, Cain had reached the top of a company whose brand was a household name. The shame is that too few African Americans moved up the corporate ladder behind him. A recent study reported that, even now, only 3.2 percent of senior leaders of large American corporations are Black.

The second phase of Cain’s career — as a small-government, low-tax public policy maven — began with his service on the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, then accelerated when he was elected president of the National Restaurant Association. Cain energized the sleepy trade association by helping to lead opposition to the Clinton administration’s proposed overhaul of the health-care industry. That work caught the attention of Jack Kemp, an apostle of fiscal conservativism — and also a former NFL quarterback and member of Congress — who invited Cain to join a commission on tax reform.

“The Colin Powell of American capitalism,” Kemp dubbed his friend. Cain’s work at the restaurant association and on the Kemp Commission made him prominent among Washington lobbyists; it was also the part of his life that produced several accusations of sexual harassment. And those ultimately torpedoed Cain’s long-shot 2012 campaign for the Republican presidential nomination, just as he was picking up unexpected momentum. Many White voters were intrigued by Cain’s success in business and his simplified tax plan — “the 9-9-9 Plan,” featuring a lower income tax and a new federal sales tax. But with only about 6 percent of Black Americans identifying as Republicans in 2012, and the Black cultural elite overwhelmingly liberal, Cain lacked a base of support on which to build.

As a survivor of aggressive colon cancer, Cain might have paid more attention to public health warnings about the novel coronavirus. But there he was last month in Tulsa, at a rally for President Trump, his smile visible, his mask nowhere to be seen. Perhaps by then, going against the grain was so deeply etched that it had become a self-defeating habit. That he was able to make his own way on his own terms, however, was a legacy worth leaving.

Read more:

David Von Drehle: John Prine was a rare poet of American song

David Von Drehle:Gil Bailey brought the music of the Caribbean to the airwaves

Jennifer Rubin: Trump’s racist housing tweet is par for his family

David Von Drehle: Joe Diffie made you turn up the volume