Congress flails as coronavirus ravages the nation and the economy stalls

What has faded is the sense of bipartisan urgency that existed in the spring and propelled Congress to act with near unanimity.

At that time, the new virus that was wreaking economic havoc around the nation was so alarming it seemed to startle lawmakers out of their partisan corners. But now the election is nearing, and the novel coronavirus is not so novel. The partisan divisions are back on Capitol Hill, and they appear to be as intractable as ever.

“The Republicans are pushing the American economy into a depression because they are unwilling to do what is necessary to prevent it,” said Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii.). “This is not the fault of ‘Congress’ generally — this is happening to America because of the Republicans. We want to strike a compromise, but their ideology prevents them from meeting the moment.”

In turn, Republicans placed blame on Democrats for letting expanded unemployment benefits lapse Friday, though the GOP did not release their own comprehensive proposal until earlier this week.

Meanwhile, the dwindling center on Capitol Hill — and those facing competitive contests this fall — are urging their leaders to take swifter action.

“Congress has to rise to the crisis. It is too serious,” said Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine), one of at least a half dozen endangered GOP senators whose political fortunes are in the balance. “If we can’t work together in a bipartisan, bicameral way in the midst of a persistent pandemic that is causing such harm to people’s health and their economic stability, then we will have failed the American people.”

Democrats and many Republicans insist it is imperative to act soon to pass another big relief bill. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) called the virus “a freight train that is picking up steam and picking up speed” Friday as she called for Senate passage of the House Democrats’ $3 trillion bill. Talks are ongoing between congressional Democrats and top Trump administration officials, and many people involved think they will manage to produce some kind of agreement in the next couple weeks.

But Republicans are divided between those like Collins who support aggressive new action and a significant minority of GOP lawmakers who think Congress has done its job and should not spend any more money at all to pile on the deficit.

President Trump’s weakening standing in the polls means there is less imperative for reluctant fiscal conservatives to rally around legislation that might help his political fortunes. The president himself has also reduced the sense of urgency for some in his party by embracing unlikely hopes that the economy can heal itself by reopening, or that the virus will disappear on its own.

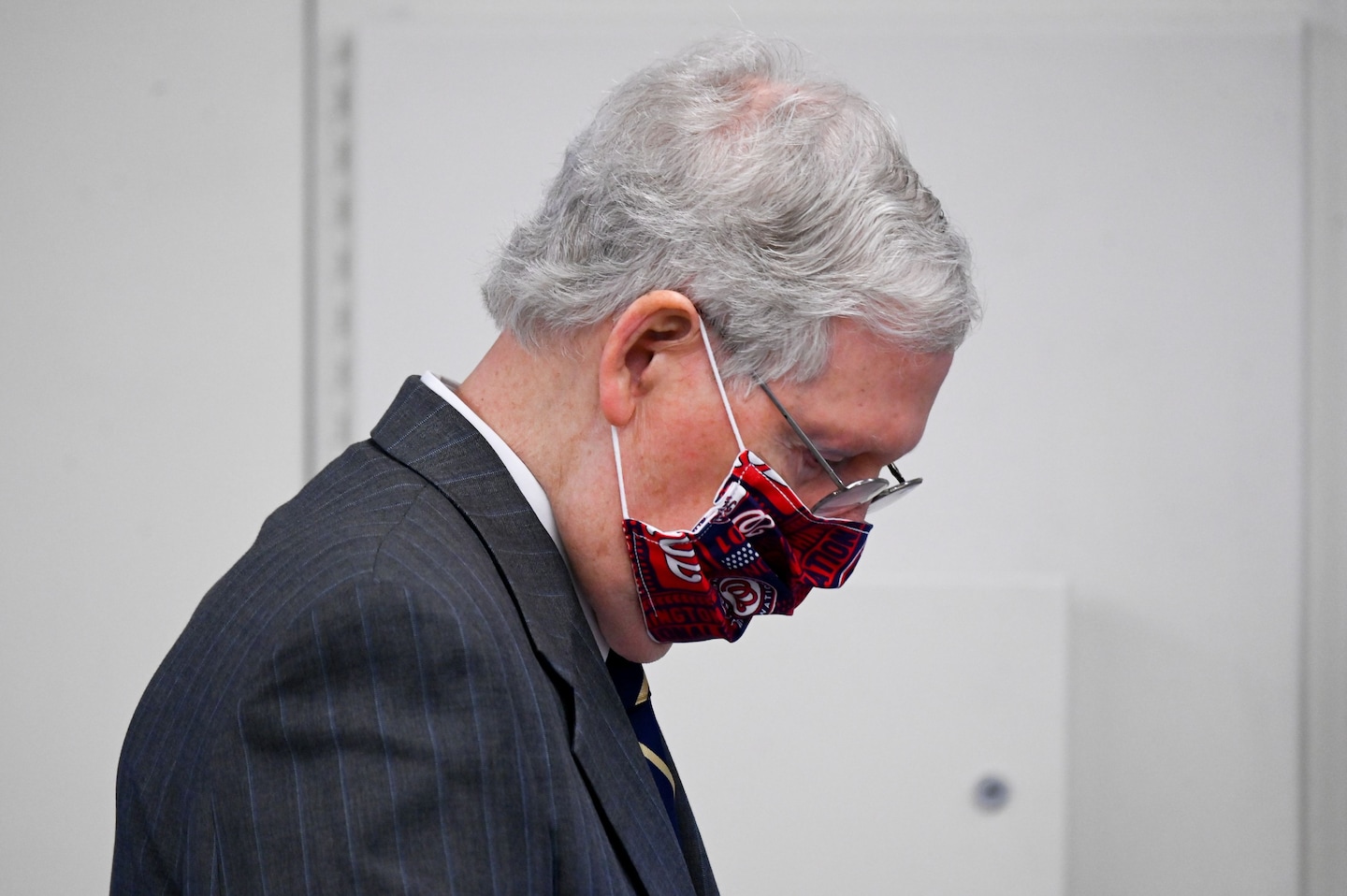

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) waited months over the late spring and summer to act, saying he wanted to see what impact the programs already approved were having before agreeing to anything more. During that time the virus itself frustrated widespread hopes that the situation might improve and began to surge in states that had reopened too aggressively.

McConnell finally released a $1 trillion bill last Monday as the GOP’s answer to the much larger bill passed by House Democrats in May, but he struggled to get consensus within his party and with the Trump administration, including complaints from members of his own conference about everything from the price tag to a new round of stimulus checks.

Facing a deadline Friday for $600 weekly emergency unemployment benefits to expire for nearly 30 million Americans, Republicans quickly started to pivot to talking about a short-term unemployment insurance fix, rendering their own bill all but irrelevant in a matter of days — with Trump himself dismissing it as “sort of semi-irrelevant” the day after it was released.

Democrats have consistently rejected the notion of a short-term fix, and in face of the GOP’s disunity they have shown little willingness to compromise on their push for the most generous relief bill possible, with an array of provisions that Republicans reject, such as $1 trillion in new aid for cities and states. Republicans say they do not think Democrats want to pass anything at all because they’d rather have a political issue; Democrats angrily reject that accusation.

After 3-1/2 years of rancor under the Trump administration, there is little trust left between the two parties, and no direct communication at all between Trump and Pelosi.

The result is stasis.

“In order to cut deals and find compromise in this hyperpartisan political environment you have to have at least a small amount of trust in each other,” said Jim Manley, who was a top aide to former Senate Democratic leader Harry M. Reid of Nevada. “The problem right now is that no one trusts their colleagues on the other side of the aisle.”

Congress rarely acts except when up against a deadline, and stopgap spending bills and partial government shutdowns have become almost routine in recent years, as Congress repeatedly offers fresh proof of its own dysfunction. As economically harmful as a government shutdown is, however, it is nothing compared with the coronavirus, which has already killed more than 150,000 Americans while simultaneously clobbering the economy. Gross domestic product dropped 9.5 percent in the second quarter of the year, the Commerce Department said Thursday — a decline that would have been even worse without the economic aid provided by Congress.

Multiple lawmakers of both parties have said the only really comparable situation is a war. Yet with the two sides so far apart on multiple issues, the prospect of failing to get any deal at all is a real possibility.

“I don’t even want to fathom that, it’s unimaginable that we wouldn’t, given the needs that the country has,” said Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.). “It would just be so bad if we didn’t that ultimately you would hope that … the fever would break.”

During the last financial crisis more than a decade ago, Congress was also divided as it struggled to pass a massive stimulus bill for the nation, although the spending at that time pales in comparison with what Congress has already approved to deal with the coronavirus. A similar phenomenon was on display then, where after finally passing the main financial bailout legislation, the sense of urgency began to abate, said Rohit Kumar, who was a top aide at the time to McConnell, then the minority leader.

“Over time these things get harder,” said Kumar, now a principal at PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. “What we’re seeing is the same natural trajectory which is on the first bill you get a fair bit of consensus and on subsequent bills it gets harder. So we’re in the ‘it gets harder’ part of the equation.”

McConnell is not negotiating directly with Pelosi or Senate Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.), leaving that up to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows. Multiple lawmakers and aides said the pair’s lack of legislative and congressional experience complicates the dealmaking process, especially after the recent departure of the White House legislative affairs director, Eric Ueland, who had many years of experience on Capitol Hill.

McConnell coordinates closely with Mnuchin and Meadows, but his posture of remove puts the onus on the Trump administration to sell any deal made with Democrats to GOP members of Congress. Republicans have been unhappy with some of the deals Mnuchin struck with Democrats early on, including the unemployment insurance payments that have now expired. Most Republicans want to extend them, but at a greatly reduced level, while Democrats want to continue the $600 weekly payments at their present level.

The two parties spent much of the past week blaming each other for allowing the payments to expire.

In the first sign of progress after days of stalemate, a meeting at the Capitol Saturday between Pelosi, Schumer, Meadows and Mnuchin yielded guardedly positive comments from all involved – although a deal did not appear imminent.

Despite the current chaos and uncertainty, Congress may ultimately find its way through to making another deal to help revive the economy and help Americans. But even as the virus rages and the economy teeters, the rancor shows every sign of getting worse before it gets better.

“Our politics is such that there must be significant political pain before hard things can get done,” said Brendan Buck, who was a top adviser to former Republican House speaker Paul D. Ryan. “That’s our forcing mechanism, and the political pain will be starting very soon.”