‘It’s clear we need the help’: Fast-dwindling federal aid pits Florida governments against each other

The fighting centers on a $150 billion federal program meant to help state and local governments purchase protective equipment, pay first responders and cover other unexpected costs associated with the pandemic. Florida received a roughly $8 billion allotment under the so-called Coronavirus Relief Fund, which congressional lawmakers approved as part of the $2 trillion Cares Act that was signed into law in March.

More than four months later, however, the money has created conflicts among cash-starved governments across the state. With infections spiking — and some of Florida’s own congressional delegation opposed to sending more help — city and county leaders are racing to grab as much cash as they can. The situation has grown so dire that cities including Miami are threatening to sue their own county just to obtain the federal support they believe they are owed.

The legal scramble is troubling enough at a moment when the coronavirus outbreak is still worsening in Florida, one of the hardest-hit states in the country. But it has taken on added urgency given the political stalemate in Washington, which already forced some city and state leaders to lay off 1.6 million workers and slash their spending amid fears that more federal aid isn’t going to arrive any time soon.

“It’s clear we need the help,” said Francis Suarez, the mayor of Miami.

Florida’s financial woes mirror much of the rest of the country, as the coronavirus continues to claim not only lives but businesses, workers and years of economic gains. Even states that had healthy finances before the pandemic have watched their circumstances sour, as companies close their doors, workers lose their jobs and people spend less on shopping and tourism — cleaving unexpected holes in governments’ budgets.

This June, DeSantis slashed more than $1 billion from the state’s new spending blueprint, including proposed improvements to walkways in South Florida, mental health centers in Miami and other potential fixes to bridges and public buildings. Florida cities and counties have faced spiraling deficits and massive cuts of their own as they enter next fiscal year, but officials across the state are bracing for the worst pain in 2021 into 2022, when their collective budget impact could be far greater.

“Cataclysmic is a good word for it,” said Dan White, the director of government consulting and fiscal policy research with Moody’s Analytics. The firm has estimated the state of Florida alone faces a $16 billion shortfall over the next three fiscal years. The gap could rise to $24 billion when you factor in local governments, other analysts have said.

“Even the best states are going to have trouble digesting something like that,” White said.

With a potential catastrophe looming, mayors from 163 cities in Florida last week pleaded with Congress to authorize more aid. In a letter, they said the money already authorized under the Cares Act is insufficient to help them cover the costs of a pandemic that has hit Florida particularly hard. And they fretted they are prohibited under law from using the dollars they have already received to close their budget deficits, a lapse that may “contribute to our economic downturn,” the mayors wrote.

Some mayors said they expected their economic situation to become even more precarious entering hurricane season. This week, Hurricane Isaias became the second such storm to make landfall this year, affirming for some mayors the immense budget trouble they may face if they are forced to contend with both a recovery and a natural disaster simultaneously.

“The economic impact would be devastating,” said Rick Kriesman, the mayor of St. Petersburg, Fla. While he said his city is in better financial shape than others in the state, he said it still can take years to obtain federal money for hurricane-related expenses — and in some cases they “never fully recover everything.”

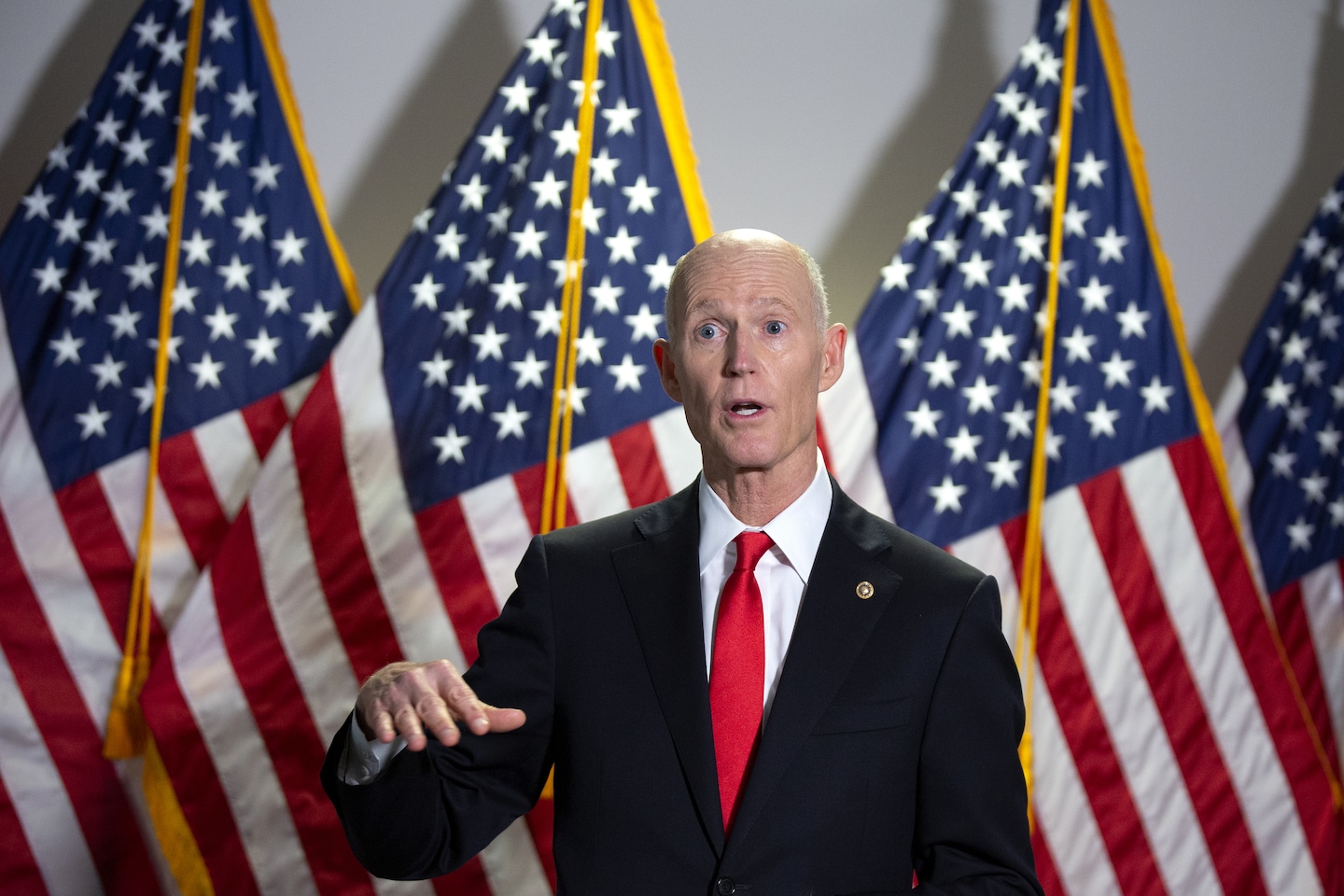

In seeking more aid, Florida officials have clashed with the White House, where President Trump on Tuesday again claimed erroneously that only Democrat-run cities and states have “suffered greatly.” On Capitol Hill, meanwhile, GOP lawmakers — including some in Florida’s delegation — have opposed sending additional dollars, too. Instead, Senate Republican leaders have prioritized making existing federal funds more flexible, as lawmakers including Sen. Rick Scott reject an attempt to enact what they refer to as a “bailout for states.”

Scott declined an interview. “He is focused on making sure any aid that is passed goes directly to help those in need, not to inefficient and bloated government bureaucracies,” Sarah Schwirian, the senator’s spokesman, said in a statement. “Florida is well-positioned to address the coming shortfall in revenue without a bailout.”

Local officials tell a different story.

“I would not term it a bailout. Everyone has been knocked to their knees by covid-19,” said Jane Castor, the mayor of Tampa, whose city is facing $52 million in lost revenue and new coronavirus-related expenses.

Suarez, the mayor of Miami, said his city’s finances had in fact been fine before the coronavirus arrived. But a $20 million surplus instead has become an estimated $25 million deficit that’s expected to grow. “We have not gotten any real significant federal or state dollars, or certainly none that would help us with our deficit,” he said.

About an hour’s drive south, in Homestead, Mayor Steve Losner said he estimates a $6 million budget hole brought about by sharp declines in tax revenue and “extraordinary expenses.” To save cash, city officials are eyeing delays to a wave of planned improvements to local parks, its power plant and fleet of police vehicles, he said.

“There’s got to be some recognition by Congress of a real need,” Losner added.

Even the dollars that Congress has authorized have proven difficult to deploy — and even harder to get — in the eyes of some of Florida’s mayors.

Under the Cares Act, lawmakers opted to dole out $150 billion in coronavirus cost reimbursements through states and their largest cities and counties, which were supposed to share it with smaller municipalities within their borders. Most of Florida’s allocation went to state leaders in Tallahassee, and only one city — Jacksonville — was large enough to qualify for direct assistance.

By the summer, DeSantis announced a plan to distribute the money more broadly, setting aside about $470 million for Miami-Dade County, the state’s most populous expanse. Carlos Giménez, the county’s mayor, said the county planned to use the aid to help renters afford their homes while assisting local businesses, including restaurants, that are facing prolonged shutdowns.

But cities balked at the county’s approach, initially fretting that Miami-Dade County had committed only to set aside about $30 million so that they could seek reimbursements for their own pandemic-related costs. While county officials this week discussed allocating more for their local municipalities, dozens of mayors still have griped that they may be left on the hook to cover coronavirus expenses they might not be able to afford.

In recent days, mayors from Miami and other cities even have said they are considering their legal options and may sue to obtain more federal aid. Giménez, the county mayor, said in response that the cities likely lack legal standing, misunderstood the county’s plans for the money and are merely trying to play politics. A spokesman for DeSantis, meanwhile, did not respond to requests for comment.

Amid the standoff, some experts said the situation might have been avoidable if Congress had acted swiftly to deliver more money in a less restrictive way.

“Every state needs additional federal aid,” said White, the analyst at Moody’s. “The economic impacts of that aid, and not receiving it quickly, are exceedingly high.”