Route concepts: When receivers get open, they didn’t do it by themselves

Part of an occasional series

So, we’ve talked about pass routes and how they work. Running routes correctly is undoubtedly important, but each individual route is just a component. To understanding how entire passing schemes work, you take what we know about pass blocking and combine that with how different routes work together. Because here’s the secret: It often takes more than one receiver to become “open.”

Huh?

This may seem rudimentary, but routes are simply the ways receivers get to a specific part of the field. Think of the entire passing game as a picture that the offense is trying to paint across the defense. Receivers disperse across the field in a specific way and then sync up with a quarterback’s drop and read progression to get to the right spot for the ball.

This is the world of route concepts, which is the Football Guy term for how routes work together. You may see a receiver open on the field and ask, “Well, why don’t you just throw it there?” Sometimes the answer is quarterback missed the read, but other times, certain receivers really aren’t meant to get the ball if the play is working correctly. It’s not because a player’s being wasted; it’s because he’s working with a group of wide receivers to attack the defense so the primary receiver can get open.

So how many “concepts” are we talkin’ about here?

There are dozens, if not hundreds, of passing concepts out there at different levels of football. There’s a family of concepts, for instance, that are just meant to get triangles in the secondary to stress defenses.

Think about it: We’re talking about all the possible ways to get between two and five people — receivers, tight ends, running backs — across the field in any combination of alignments. And there are myriad ways to adapt concepts with personnel shifts and motions and route tags and truncations to meet all the different situations that may occur.

But to show how elements work together, I’ll group things into three buckets and take a look at just one concept in each.

Buckets?

Not every pass play is designed to score a long touchdown. We’ll start with the short stuff, sometimes referred to as the “quick game.” If the quarterback is under center, he’ll take a three-step drop to make these throws. If he’s in the shotgun, he’ll barely take a step at all after catching the snap. These plays and routes are designed to gain a little, not a lot. (Sometimes they gain a lot anyway, thanks to a receiver’s athleticism or a defensive breakdown or both.)

On first and 10,?this family aims to get you to second and five. Third and short? Well here’s a nice way to move the chains and perhaps beat a blitz. (Think about how, in the Madden video game, slants always work when you need some yards.)

As an example, I’ll use “stick,” a staple of the West Coast offense that made the 49ers a dynasty in the 1980s.

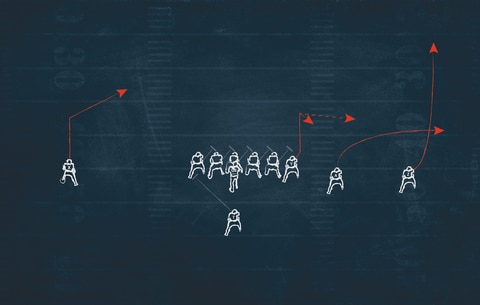

We’ll call the three-receiver side the “front” side and the single-receiver side the “back” side.

On this hypothetical play with nice six-man slide protection, it doesn’t really matter what that backside receiver does. Sprint 30 yards downfield, run a slant, have a party. The money is with the Nos. 2 and No. 3 receivers (counting right to left).

No. 3 runs a route that’s dependent on the coverage (think about the way we described Jason Witten’s bread and butter in our previous installment on routes). He feels the defense, and then either sits in a hole or runs an out route. No. 2 runs a speed out and hopefully is heading into a void. And that void is created because No. 1 is running a “clear out” up the field, with the goal of taking the cornerback with him on a jaunty stroll. That creates the void for No. 2, who has created a void for No. 3. Pick on the linebacker and make the throw.

It’s worth remembering with all of this that the players are generally more important than the scheme. All that stuff about “stick” being?a short passing concept here to gain just a few yards, with the front-side deep route there just to create space? That’s all true — except when it’s being run by Randy Moss.

The short stuff is cute, but can we go deeper?

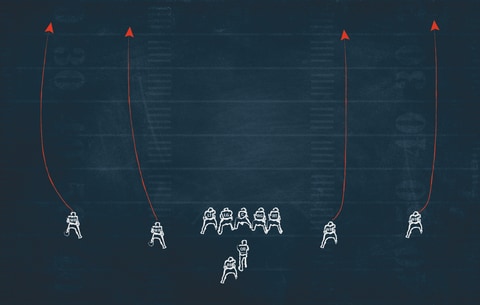

All right, let’s stretch the field a little bit with an old staple: Four Verts … with a twist. You probably think of it as a deep passing concept. I mean, look at it in its stock version, which could be taken from any air raid playbook.

I don’t blame you. Frankly, I agreed with you until I asked a coach who loves to run it — Jerry Taylor, passing coordinator at Columbia — and he explained it to me.

Four Verts may have four vertical route stems, but just because a receiver starts sprinting up the field doesn’t mean he’s going to end up deep. That can depend on the defense.

That No. 2 receiver on the left, for instance, can have a lot happen based on a particular coverage. By the time he’s 10 yards downfield, his route may look nothing like the “go” route you may associate with the concept.

“If they’re running cover-4 to the boundary, four verticals could in theory turn into a dig and a sit route,” Taylor said. “That’s four verticals. That’s crazy. That’s why I say four verticals — as a fan, understand that four verticals does not have to be vertical.”

What he means is that “four verticals” can be adapted in a way that brings these routes across the field and into the quarterback’s vision if he doesn’t like what he sees on the other side of the field.

Reading the whole field is hard, particularly with the wider hashes in college, where a throw to the opposite side of the field is pretty long. So routes that adapt to coverage and bring those receivers back toward the middle of the field can make things easier for the quarterback if his initial reads are covered.

This is what Four Verticals could end up looking like at the end. It’s much more medium distance for a 10-15 yard completion:

Okay, cool, but what’s it look like when we really want to sling it?

Deep and shot plays are sometimes grouped together. There aren’t a ton of these plays, maybe about five in a given week’s game plan. And they’re for when a team needs at least 30 or 40 yards.

Whereas the quick game calls for three-step drops from under center, this is as many as seven steps or often play-action with as many as eight blockers. This is where protection, and quarterback drop really tie together.

A team attempting to throw that deep is gonna need some time to allow even world-class athletes to get down the field. So maybe the quarterback pulls a seven-step drop or a play-action fake to try to get the safeties to pause and to allow more time for the receivers to get downfield.

This Titans play from the 2019 season that we linked to in our blocking explainer works because they had the ingredients to make it work:

- A credible running game in Derrick Henry;

- Solid max protection;

- Wide receivers who can beat man coverage and excel after the catch in A.J. Brown and Corey Davis;

- A quarterback who can throw accurately down the field in Ryan Tannehill.

And when it works, it works.

If you’ve been following along with the series you know a little bit more about the passing game than when we started, but what he haven’t talked about is how to view the way defenses defend it. That’s what we’ll do next in discussing the basics of pass coverage.

Read more from the “Watching Football Smarter” series: