Why I feel insult when Trump mispronounces Kamala Harris’s name

My name, Nana Efua, roughly translates to “Chief or Queen Mother (Nana) born on Friday (Efua).” From birth, I have had the title of a Ghanaian dignitary, marking my father’s ancestral heritage. As a child, I was reminded of this heritage as added pressure to behave. As I have aged, my name has served as a personal declaration, or affirmation, that I am descended from a family of distinction and that my actions and words should proceed accordingly.

My name is a message to everyone I interact with: It signals my identity, details about my birth — and that I should be treated with respect.

I have met only one other Nana Efua, so I’m used to my name being unfamiliar to most people. I’m often asked, Is my first name one word or two? (Two.) Is it French? No. (Pronounced Na-NEF-wha, quickly, like Vanessa.) I vividly recall how on the first day of school, when teachers reached me on the roll call, they hesitated at the jumble of consonants and vowels. Other students would stare and chuckle when I spoke up, breaking the silence.

But more than those awkward moments, I remember the teachers, co-workers, strangers and soon-to-be friends who took the time to get my name right. People who asked me over and over to repeat my name, who broke it into easily pronounceable parts to get it right themselves. I have even had co-workers call my voicemail to hear how I pronounced it, not wanting to offend me by asking. These efforts are signs of respect for me and my culture.

Some Americanization of foreign names is, of course, understandable. Some find it difficult to do the trill or roll in a Spanish name, for example, or to pronounce certain Arabic letters. I grew up in the Midwest, and my American accent renders a slight tonal change that means even I pronounce my name differently than my Ghanaian relatives do.

Yet this is different from people teasing, taunting or otherwise intentionally mispronouncing my name. Some people wield mispronunciation like a weapon, trying to belittle me. Some who have said my name wrong quickly move on, retorting: “I’ll just call you Nana. It’s what I call my grandma!”

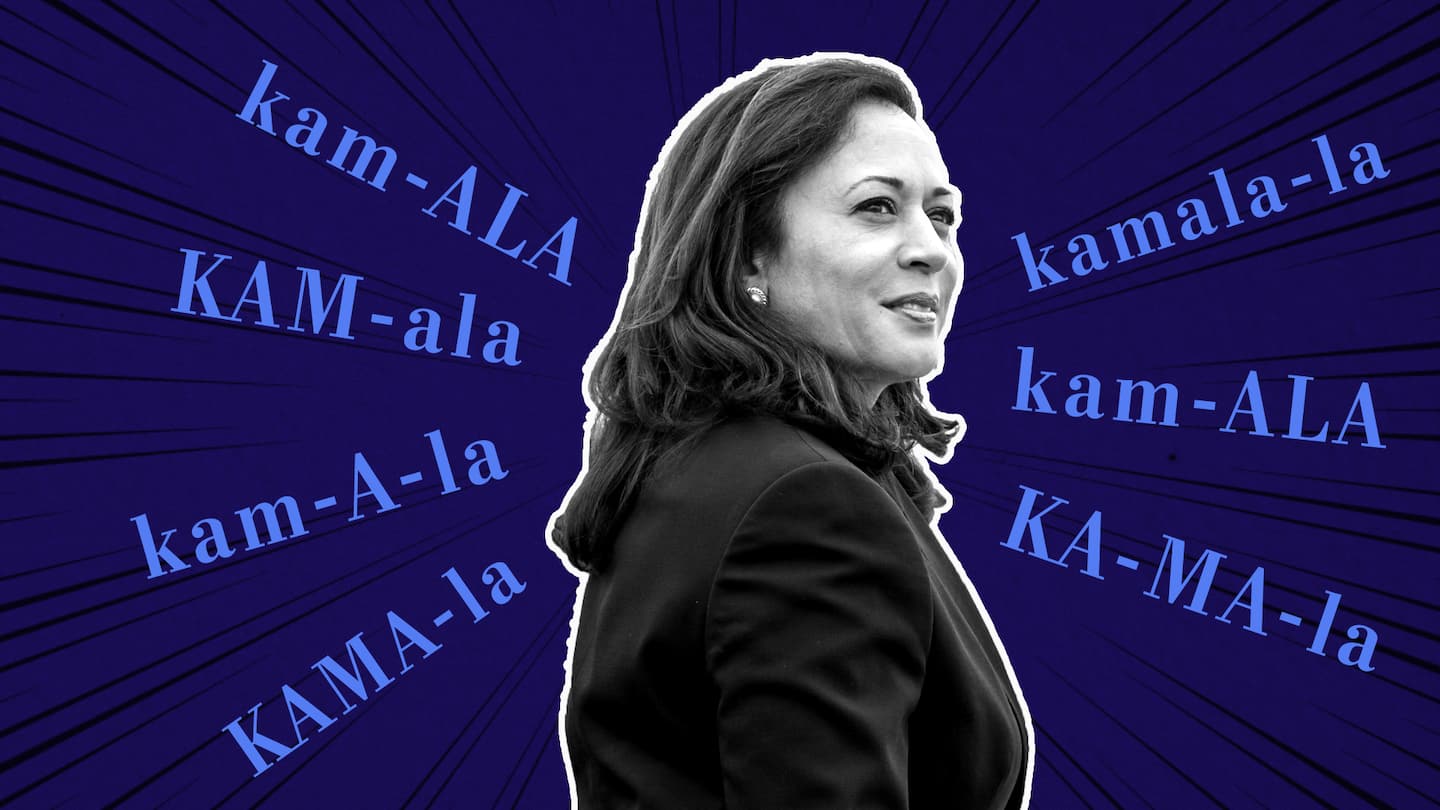

This behavior might be expected in elementary school. It’s improper and insulting from elected officials. The president, who has repeatedly referred to KAH-ma-la and COMMA-la, said this week: “Kamala. Kamala. You know, if you don’t pronounce her name exactly right, she gets very angry at you.” At a recent Trump rally in Georgia, Sen. David Perdue (R) also denigrated and dismissed the Democratic vice presidential nominee, saying “Ka-mal-a, Comma-la, Ka-mala-mala-mala” and then “whatever.” These attempts to mock and otherize Harris resonated with me and many other Americans.

These denigrations say more about Trump, Perdue and others — their insecurities, their lack of sophistication — than about Kamala Devi Harris, whose first name means lotus in Sanskrit and who is the first mixed-race woman on a major-party national ticket.

Staff for Perdue, who serves in the U.S. Senate with Harris, said after the rally that his mispronunciation was unintentional. “I absolutely meant no disrespect to the Senator from California,” Perdue emailed one of my Post colleagues. “My role in this is to point out the differences in what their agenda is and what our agenda is. A lot of Democrats will do or say anything right now to hide their radical, socialist agenda.”

A lot of people will say anything to explain away their racism, too.

These insults have rocketed around social media, where people with uncommon names have posted about painful teasing — our shared experience. It’s easy to tell us to ignore these insults — sticks and stones and whatnot. But when we don’t call out attacks that use words, what might they become?

Much has been said about the polarization of our country. Preventable slights widen that divide. A little goes a long way in terms of patience, apologies, asking for repetitions — and not imposing your shorthand on someone else. Plus, my father has always said that my name is “too meaningful to give it a nickname.”

Taking care with a person’s name respects their identity. I would ask those who cannot extend me this basic courtesy to not engage with me at all. Because, as Shire wrote, “my name doesn’t allow me to trust anyone that cannot pronounce it right.”

Read more: