5 takeaways from Day 4 of Trump’s impeachment trial

Democrats have cited Trump repeatedly calling for his supporters to “fight,” so Trump’s team played lengthy videos featuring Democrats using that word.

Democrats have decried Trump’s challenge to the election results, so Trump’s team played clips of Democrats in the past contesting the election of Republican presidents.

Democrats emphasized that Trump claimed even months before the 2020 election that if he lost, it would be stolen, so Trump’s team played videos of some Democrats claiming an election had been or could be stolen.

That last one gave away the game.

To rebut the argument from impeachment manager Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-Tex.) that Trump had laid a predicate for what became the Jan. 6 riot by predicting a stolen election, Trump’s legal team played videos that showed Democrats … not doing that. Some clips showed Democrats claiming 2018 Georgia governor candidate Stacey Abrams’s (D) loss resulted from a stolen election, but those came after the election. Another showed Hillary Clinton saying in 2019 that you can run a great campaign and still have an election stolen. But this, too, came after the fact, and it cited Russia’s well-established interference in a close election. Now-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) were played questioning the security of our elections in 2005. But none of the clips featured any of them predicting their side could only lose through fraud, as Trump did.

It was a complete non sequitur.

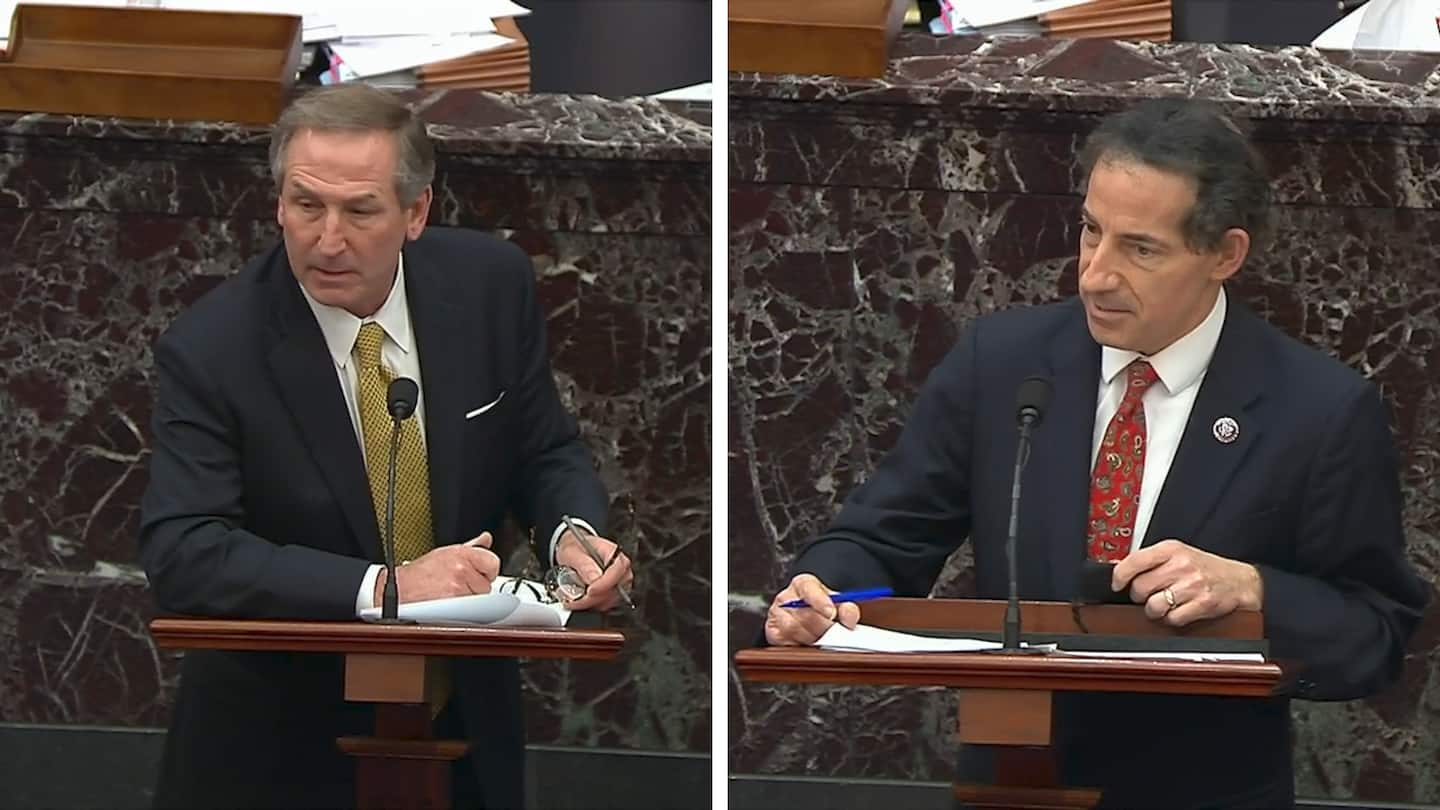

Trump lawyer Michael van der Veen at one point argued this wasn’t whataboutism.

“I am not showing you this video as some excuse for Mr. Trump’s speech,” van der Veen said. “This is not whataboutism. I am showing you this to make the point that all political speech must be protected.”

But the argument was clearly that lots of politicians do something similar to Trump. Van der Veen might not have been saying Democrats should be culpable for anything, but saying “everyone does it” is certainly a form of whataboutism.

Cherry-picking is always possible in these settings. Trump’s comments about fighting, in a vacuum, were unremarkable in modern political life. He was hardly the first politician to contest an election or even claim it was stolen. And political violence has occurred before. Some of the comments played of Democrats were in poor taste or ill-advised.

The question before the Senate, though, is whether the combination of Trump’s actions — up to and including theories that were rebuked over and over again in courts, along with warnings that his rhetoric could lead to the kind of events we saw Jan. 6 — amounted to incitement.

If any of the Democrats claimed they couldn’t lose except through fraud, the comparison would be valid. If any of the clips of Democrats preceded actual violence by supporters who cited their encouragement (as is the case with Trump, repeatedly), it would be valid to question their culpability. And if any of them offered anywhere near the volume of completely baseless and debunked claims that Trump did before such violence, it would be even more valid. That’s just not the reality.

2. Curious answers on the timeline

After the Trump team’s presentation, we moved to the question-and-answer portion. Much of this is bogged down by leading questions with no real effort to elicit new information, but some of it should raise eyebrows.

Such was the case on the timeline of what Trump knew and when early in the Capitol riot.

GOP Sens. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) and Susan Collins (R-Maine) asked when Trump actually knew that the Capitol had been breached — given his delayed response (even by the accounts of allies). Rather than answer the question, though, van der Veen said that, “with the rush to impeachment, there’s been absolutely no investigation into that.” This is his client, and it’s a central question.

In another effort to get at the timeline, Collins and Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) asked whether Trump knew that then-Vice President Pence had been evacuated from the Capitol when he attacked him in a tweet at 2:24 p.m. on Jan. 6. Trump lawyer Bruce Castor responded, “The answer is no. At no point was the president informed the vice president was in any danger …” He again cited the rushed process.

That’s a big claim — especially given Sen. Tommy Tuberville (R-Ala.) this week disclosed that he told Trump in a call shortly after 2 p.m. that Pence had been evacuated. Trump’s legal team later cited Tuberville’s account amounted to “hearsay.”

It’s not totally clear that happened before Trump’s tweet, but Castor’s response suggests Trump’s lawyers have gone over the timeline with him. How do they not know when Trump knew about the siege, but that he didn’t know about Pence’s evacuation at a very specific time?

These are questions that witnesses could conceivably shed light on, but apparently we won’t get those.

Van der Veen also suggested, when he was asked again about Trump and Pence, “I have a problem with the facts in the question because I have no idea, and nobody from the House has given us any opportunity to have any idea.” Again, this is his client.

Lead Democratic impeachment manager Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) later responded by expressing exasperation and suggesting Trump’s lawyers allow him to testify to clear things up.

3. An extremely broad definition of free speech

The Trump team did address Trump’s role eventually. It homed in on free speech. But rather than parse Trump’s comments and how they fit with established limits on speech, it asserted an extremely broad vision of what a president is entitled to say.

“The House managers argue that the First Amendment, and I quote, ‘does not shield public officials who occupy sensitive policymaking positions from adverse actions when their speech undermines important governmental interests,’” van der Veen said. “That is flat wrong.”

“Mr. Trump was elected by the people. He is an elected official. The Supreme Court says elected officials must have the right to freely engage in public speech. Indeed, the Supreme Court expressly rejected the House managers argument in Wood v. Georgia, holding that the sheriff was not a civil servant but an elected official who had core First Amendment rights which could not be restricted.”

We knew based upon briefs filed by the Trump team that it would lean on the free speech argument, but we didn’t know just how absolute it would assert that right is — especially given that there are well-established limits on such rights in public discourse, including defamation and incitement.

It turns out, very absolute.

But the key cases they cited, Wood and Bond v. Floyd, carry very limited applicability to Trump’s case.

Wood didn’t say an official’s “First Amendment rights … could not be restricted.” Instead, it said officials may speak freely with regard to grand jury proceedings except when their speech creates a threat to the proceedings. Bond dealt narrowly with whether a politician could be prevented from assuming an office to which they had been elected because of their statements about government policy.

None of the case law cited said a president or any official has anything amounting to an absolute right to free speech.

4. Lecturing on facts, while getting facts wrong

The Trump team got off to a rather inauspicious start. Their early presentation focused on the idea that Democrats had butchered the facts. And they had some points, including when it comes to the impeachment managers apparently attaching a blue check mark to a Twitter account whose tweet they had used.

But the Trump team didn’t exactly adhere to the facts themselves.

This appears to refer to John Sullivan, who was arrested and released in mid-January. There is no evidence Sullivan is anything amounting to a leader of antifa, despite the claims of Trump allies like Rudy Giuliani. As The Washington Post has reported, Sullivan has floated around many political movements, including the Black Lives Matter movement, but he’s widely regarded with suspicion among those activists.

All three of Trump’s lawyers — van der Veen, Castor and David Schoen — echoed a popular claim that Trump’s impeachment would effectively negate the votes of 75 million Americans. Schoen said those voters would be disenfranchised by a vote to convict, while van der Veen and Castor alleged such a vote would “cancel” his voters.

Trump actually got 74.2 million votes. This might seem like a small point, but it speaks to how much this effort was geared toward Trump’s fanciful claims — and apparently speaking to the “audience of one.”

Another rather remarkable contention came with regard to the tweet mentioned at the top. Not only did the Democrats apparently add a blue check mark to add heft to the user’s profile, but Schoen also accused them of misconstruing the user’s sentiment. While Democrats said the woman in the tweet had said Trump supporters were bringing the “cavalry,” instead she spelled the word “calvary.”

“The problem is the actual text is exactly the opposite,” van der Veen said. “The tweeter promised to bring the calvary — a public display of Christ’s crucifixion, a central symbol of her Christian faith — with her to the president’s speech — a symbol of faith, love and peace.”

It’s possible the woman did mean calvary, but this is a common misspelling. What’s more, “the calvary is coming” is not an expression; “the cavalry is coming” is. The woman also tweeted during the Capitol riot telling people to go into the Capitol.

That was a case in point for the defense. They know they aren’t going to lose, so they might as well gear toward what the client wants to hear, even if it obscures the issues in the case.

5. The question from here

To the above point: What matters now, practically speaking, is how the Senate votes. There were few illusions that we would ever get anywhere near the 17 GOP votes needed for a conviction. In fact, we’ve only ever seen one member of a president’s party ever vote for that in an impeachment trial.

The Trump team’s presentation clearly reflected that reality. And whatever its flaws — most notably in Castor’s presentation Tuesday — it seemed very unlikely to alter that expected outcome in any significant way.

Rather than delving much into Trump’s culpability for the Capitol riot or what he said and when, his legal team instead focused not just on what Democrats had said and broad assertions about free speech, but also on the constitutionality of the proceedings. It seemed geared toward giving Republicans a series of reasons to excuse their votes that didn’t involve actually vouching for Trump, which those Republicans have signaled they aren’t terribly inclined to do. In fact, several of them, who now seem likely to vote to acquit, have directly blamed him in one fashion of another.

The trial isn’t over yet, but Democrats have thus far signaled they’re not inclined to call any witnesses who might fill out their case or significantly expand on the evidence against Trump, beyond his public comments and the video evidence on Jan. 6. Democrats must know that even such evidence probably wouldn’t sway enough votes — even if it might matter in the court of public opinion.

But with the trial heading toward a close now, there’s no real reason to doubt the outcome.

The biggest remaining question is just how many Republicans might vote against Trump. The previous record, as mentioned, is one — Romney voting to convict Trump a year ago. Several GOP senators sound open to conviction. Even some from conservative states, including Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.) and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), have suggested they’re free agents, while sending other signals that align with their party.

We shall see, but even a handful of GOP votes against Trump would be historic, while insufficient.