Ten years ago, 241 Texas power plants couldn’t take the cold. Dozens of them failed again this year.

Facilities owned by Fortune 500 energy giants NRG, Calpine Corporation and Vistra Corporation, all headquartered in Texas, and the Chicago-based Exelon, experienced shutdowns during last month’s winter storm as well as during the state’s last historic cold snap a decade ago, according to a review by The Washington Post. In testimony to state lawmakers, documents for shareholders and statements to The Post, the companies have said that last month’s problems occurred at least in part due to a failure to properly winterize equipment — in other words, to implement certain upgrades designed to protect power infrastructure from the cold. The same issue contributed to their shutdowns back in 2011.

“The entire energy sector failed Texas. We know we can do better and we must do better to make sure that this never happens again,” said Mauricio Gutierrez, chief executive of NRG, while testifying before Texas lawmakers last week. “We did suffer our share of unit problems … for that reason, we own it. We did not perform as well as I would have hoped.”

Publicly owned power generators Austin Energy and CPS Energy, which provide electricity to San Antonio, also experienced problems during both storms, according to data provided by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), a nonprofit that operates Texas’ power grid and energy trading market.

Wind energy providers also had severe problems, likely because of the icing of the blades on wind turbines, officials have said. Most did not exist 10 years ago, but one exception is the Bull Creek wind farm in West Texas, which went offline during both the 2011 and 2021 freezes. During last month’s storm, according to ERCOT data, the company reported 10 separate partial or complete outages.

The 2011 blackouts, which affected more than 4 million power customers in the state, prompted multiple investigations and calls for reform. A new law passed that same year required power generators to submit winterization plans each year to the agency that regulates them, called the Public Utility Commission of Texas. The commission also tripled the cap on the price of wholesale power, hoping generators would have an incentive to prepare for another cold snap in order to make extra money and to avoid losing more.

It wasn’t enough to prevent a far bigger disaster a decade later, when temperatures dipped far lower and for a much longer period of time. Though exact figures on the number of people left in the dark are not yet available, state officials have said the power outages last month were five times more severe than in 2011.

Millions of Texans lost heat, light and water last month. Many resorted to boiling snow, pitching tents in their living rooms to keep warm, and moving in with friends and neighbors, forgoing the warnings of public officials to socially distance during the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. The state agriculture commissioner warned that the food supply could be disrupted.

At least 50 residents died just in the Houston region due to circumstances related to the plunging temperatures and power outages, the Houston Chronicle reported. Hundreds of thousands across the state still lacked clean water earlier this week.

Generators’ identities shielded

Just as they did a decade earlier, state politicians have demanded answers and vowed to make immediate changes.

Gov. Greg Abbott and Attorney General Ken Paxton, both Republicans, called for investigations into ERCOT and some of Texas’ power companies. Lawmakers fired the chief executive of ERCOT this week, and they’ve also had harsh words for the organization’s board members, leading more than half of the board to resign. They also pressured the utility commission chair, who is appointed by Abbott, to quit.

Yet the identities of the power generators who played a role in last month’s crisis remained largely secret until Thursday, when ERCOT released a partial “forced outage” list of the 356 facilities that went offline during the freeze. The shutdowns forced a total of about 46,000 megawatts of power ― enough to light up more than 7 million homes ― off the grid, according to ERCOT.

The full list of plants that malfunction during a weather emergency is not routinely released until 60 days after the storm, according to state rules, in order to protect confidential business information and prevent companies from colluding with each other. Given the international interest in last month’s freeze, ERCOT agreed to release the list earlier — but only for companies that agreed to disclose the data to the public. Some did not.

“They are here to make money, but they are also providing an essential public good. If they want to be seen as good actors and key players then they would share this information so that we can all see it and make the best use of it,” said Kaiba White, who works for the Texas chapter of the left-leaning advocacy group Public Citizen. “But I think it’s also the responsibility of the Public Utility Commission for sure to force that to happen.”

Andrew Barlow, a spokesman for the commission, said in an email that commissioners do have discretion to waive the confidentiality rules, but that “such waivers tend to focus on immediate health and customer protection situations when determining which rules to suspend,” he wrote in an email.

Ken Anderson, who served as chairman of the utility from 2008-2017, disagreed with that assessment.

“I think it’s essential that ERCOT release the specific units that went down, who their owners are, and the reason that each particular unit failed or tripped off,” he said in an interview. “The extraordinary circumstances justify it. Before the legislature, and frankly, before the PUC can decide what needs to be done to minimize a future event like this, we need to know the cause.”

Releasing the full list would help policymakers and members of the public determine the extent to which February’s debacle could have been avoided. Although the 2011 storm was not as destructive as the one that swept across Texas last month, it contained clear lessons for an energy system unaccustomed to dealing with cold weather.

As temperatures hovered in the low teens for several consecutive mornings a decade ago, the power system in Texas experienced widespread failures. Pipes, water lines and valves froze solid at dozens of power plants. Wind turbine blades iced over.

Investigations by state and federal regulators later concluded that the leading cause of the outages was the freezing of sensing lines, essentially small pipes that contain standing water to measure pressure. When the water in the sensing line freezes, the generator system itself gets faulty pressure readings, which can trip the generator.

In all during the 2011 freeze, equipment failures affected 241 plants owned by 41 companies, leading to rolling blackouts that took power offline for hours at a time. The blackouts affected some 4.4 million customers, according to a report released months after the event by two federal energy regulators.

The rolling outages led to widespread calls for power generators to do a better job preparing their equipment for winter weather.

Fault ‘shared by many’

With an investigation into the specific causes of the blackouts in its earliest phases, it’s unclear whether the 2021 equipment failures bear any resemblance to those of a decade earlier. At least one executive claimed the crisis was caused primarily by a shortage of gasoline. But in testimony to state lawmakers last week, executives from companies admitted they didn’t prepare properly.

“Two of our power plants failed because of winterization. … That’s my fault,” said Thad Hill, chief executive of Calpine Corporation. At least two of his company’s plants failed last month and during the 2011 freeze.

Gutierrez, the NRG chief executive, told lawmakers his company experienced power failures last month at its coal-fired power plant in Limestone County, Texas, and another at Greens Bayou in the outer suburbs of Houston. NRG experienced failures at those same locations in 2011.

The more recent failures are still being investigated, Gutierrez said.

“We are going to look at our winterization programs with a new benchmark, with a new baseline, that was defined by this unprecedented winter storm,” he said.

Asked to provide more details, the company declined further comment.

For Exelon Corporation, which has a relatively small footprint in Texas, both storms knocked out the company’s Handley power plant in Fort Worth. The freeze last month also took down two newer power plants, according to financial records made public by the company.

Bill Gibbons, an Exelon spokesman, said the company’s gas-fired plants were among those that experienced some outages. The situation was made worse by “cascading problems affecting the grid” as the company was squeezed between soaring demand from customers and a limited supply of gas.

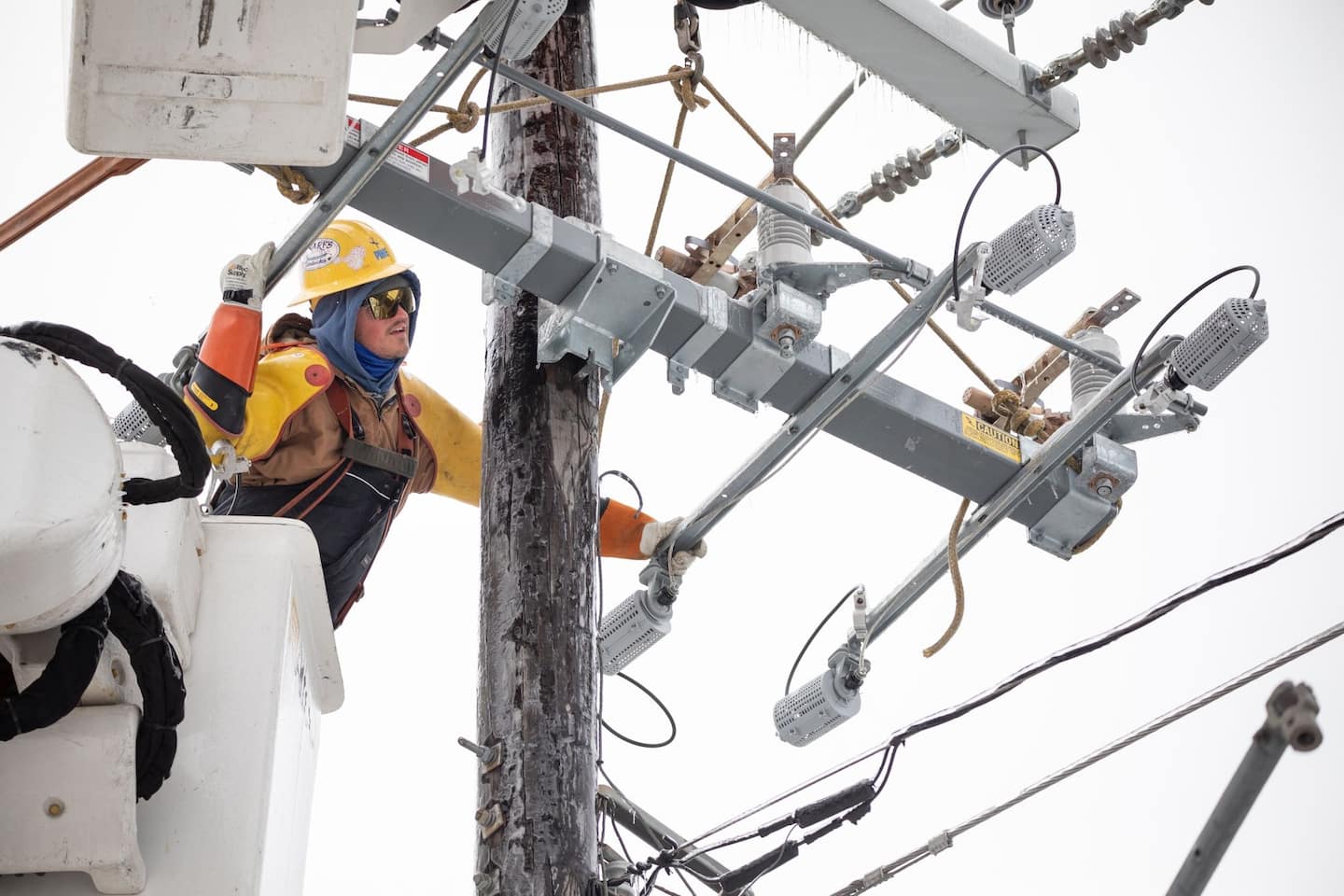

“Our teams worked around-the-clock in subfreezing temperatures to bring the plants back online as soon as possible to help support our customers and the grid,” Gibbons said. “We continue to investigate the multiple, complex factors that led to the outages, and we are committed to working with ERCOT and all of our partners to ensure an event like this does not happen again.”

The chief executive of Vistra Corporation, the largest energy provider in Texas, told lawmakers the company performed relatively well during the storm now dubbed “Snovid 2021” because it coincided with the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Still, he acknowledged the crisis exposed a need for major reforms.

“During the covid our men and women went into work at the power plants, had to work next to each other within six feet, and we kept them safe through all of that. But somehow, we could not solve the riddle of a winter storm,” said Curt Morgan, chief executive of Vistra, which operates nuclear and gas-based power systems.

Records released by ERCOT show that 10 gas and coal facilities owned by Luminant, a Vistra subsidiary, went offline during the 2011 outages, and the company paid a $750,000 fine to state regulators related to the event. Morgan told lawmakers last week that his company worked hard to improve. The company devised a checklist with hundreds of required upgrades and spent $10 million to prepare for last month’s storm.

Morgan said those actions made a difference: The company believes it produced about 30 percent of the state’s power during the week of the freeze. Still, at least three of its plants that went down in 2011 also tripped offline in 2021. One of those, the Stryker Creek Power Plant in East Texas, malfunctioned about half a dozen times during the freeze. The breakdowns caused more than 1,000 megawatts per hour ― enough electricity to power nearly 200,000 homes ― to go offline.

In an email to The Post, a Vistra spokeswoman said: “Some of our plants, including Stryker Creek, did have issues due to the historically cold temperatures. However, the bulk of our gas fleet’s unavailability was due to a lack of natural gas.”

Morgan said the same in his testimony to lawmakers last week. He said the company could take “common-sense” steps to better prepare for colder weather, but that the failures happened primarily because the natural gas industry hadn’t winterized its own equipment and couldn’t get fuel to the power plants.

“The big story in my opinion was the failure of the gas system to perform. That went all the way from the wellhead, where they froze up to get gas, into the lines that went to the processing,” he said, adding, “I think there is accountability to be shared by many in this, including my company, and I hope to do better.”

Natural gas failures under wraps

Members of the Texas Railroad Commission, which oversees the natural gas industry, forcefully disagreed with that assessment when speaking before lawmakers. The commission’s chairwoman, Christi Craddick, told lawmakers more than 99 percent of residential customers did not lose natural gas in their homes during the storm, and that transmission lines transporting natural gas to power generators performed well.

“These operators were not the problem. … The oil and gas industry was the solution,” said Craddick, a Republican and one of three elected commissioners on the agency .

She added that any delays in delivering natural gas “could have been avoided had the production facilities not been shut down by power outages” — pointing the finger squarely back at power generators and ERCOT, responsible for managing power outages during emergencies.

Asked by one state lawmaker if she was familiar with natural gas companies’ own winterization efforts, she answered, “I think it’d be better if you’d ask them. … If you’re a prudent operator, you ought to weatherize. That’s something we’ll continue to have a conversation about.”

It’s still unclear which companies in the natural gas industry may have contributed to problems during the freeze. Unlike for power generators, there is no rule requiring regulators to release the names or the details of any malfunctions experienced by natural gas drillers, processors or transporters, even after 60 days.

For companies that are publicly owned, some details have trickled out. Comstock Resources, a gas drilling company controlled by Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, appeared to perform well. “We were able to get super premium prices” on natural gas, chief financial officer Roland Burns said in a Feb. 17 call with investors.

Comstock pushed sales in the energy market, he said, and “that’s going to pay off handsomely.” The cold snap that devastated Texas was “like hitting the jackpot,” Burns said.

That remark caused a stir, and last week a company spokesperson relayed a message from Burns in which he apologized and said “the description was inappropriate and insensitive.”