Could the Supreme Court give Republicans more control over how to run elections?

But then four conservative justices opened the door to something else much more worrisome for the left: They indicated they’re open to letting state lawmakers run federal elections without state courts or even the state constitution having a say.

It’s based on a conservative push of something called the “independent state legislature” doctrine, and it would be a drastic change from the way the Supreme Court has seen the role of state courts — as a check on legislatures, reports The Washington Post’s Robert Barnes.

And it comes as former president Donald Trump continues his efforts to undermine faith in federal elections, primarily by pressuring state legislatures to try to overturn his election loss. “It would throw election administration into nationwide chaos,” the North Carolina League of Conservation Voters argued to the Supreme Court.

Here’s what the doctrine means and how it could change elections, perhaps by 2024.

What the ‘independent state legislature’ doctrine means

It’s an extremely literal reading of the Constitution, specifically the part that governs elections, which says: “Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.”

It’s a legal theory that’s been pushed by conservatives for two decades. The court hasn’t paid it much attention, write scholars Eliza Sweren Becker and Michael Waldman. George W. Bush tried to use it in his contested 2000 election to argue that Florida’s Supreme Court was taking away the legislature’s right to decide who won in that state; it drew only three votes.

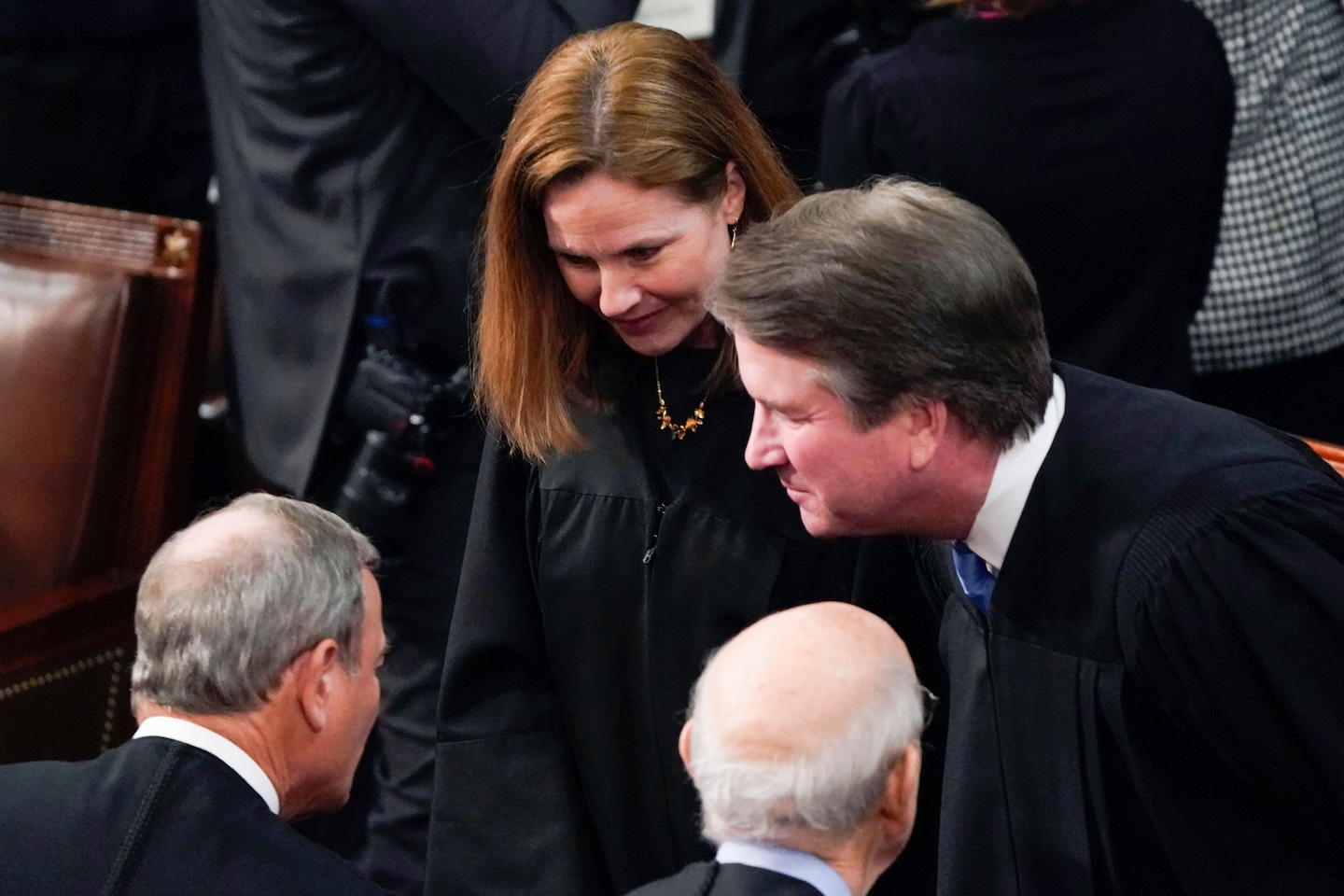

But it regained prominence in the 2020 election, when Trump urged legislatures in states he lost to overturn the popular vote based on dubious, unproven claims of fraud. Around this time, some conservatives on the Supreme Court — such as Justices Brett M. Kavanaugh, Neil M. Gorsuch and Samuel A. Alito Jr. — were sympathetic to GOP arguments about the legislature having absolute authority over elections.

This year, the doctrine came to the attention of the Supreme Court in gerrymandering cases. Republicans in North Carolina argued that the Supreme Court should allow them and only them to draw maps, because they are the majority in the legislature, and the Constitution says the “legislature.”

“The North Carolina courts have usurped [the legislature’s] constitutional authority,” North Carolina Republicans said of their maps being thrown out by that state’s courts.

(Both sides gerrymander when given the chance, but Republicans have more opportunity to do it because they control more state legislatures, which get to draw maps in most states.)

On Monday, four conservative justices seemed open to GOP legislators’ arguments. Alito called the issue “an exceptionally important and recurring question of constitutional law.” Kavanaugh said it was too close to an election to decide this now, but he essentially urged Republicans to bring up the case next term.

In 2020, Gorsuch endorsed the idea, writing: “The Constitution provides that state legislatures — not federal judges, not state judges, not state governors, not other state officials — bear primary responsibility for setting election rules.”

The case against it

Did our Founding Fathers, who so carefully weighed checks and balances in government, really mean to give one body absolute authority over elections? The longer-standing reading of the elections clause in the Constitution is that when it says “the Legislature thereof,” it means all of state government — the legislature, state courts, the governor, ballot initiatives by citizens, and the state constitution that governs it all.

“The Framers’ inclusion of the Elections Clause was driven by two overlapping concerns of current relevance: a focus on representation and a distrust of state lawmakers,” write scholars Becker and Waldman.

“The evidence shows that the framers of the Elector Appointment and Elections Clauses … expected that state constitutions would impose substantive limitations on ‘legislatures,’ ” writes researcher Hayward Smith.

For a century, the Supreme Court has agreed with this interpretation, as recently as 2015 in a gerrymandering case in Arizona.

What could happen if the court takes up a case on this?

If the court takes this doctrine up and agrees with it, it could mean politicians could gerrymander without courts stepping in. Or that courts couldn’t chime in on voting laws that may violate the state constitution. Or, in its most extreme example, that legislatures could decide how to allocate electoral votes in a presidential race without being boxed in by courts or their constitutions. (Though there is a clause in the Constitution that says Congress can step in to overrule such a scenario.)

For now, this is still a hypothetical. If the court takes up the case, we don’t know if the justices have the votes to make any substantial changes to how elections are run. They’d need five votes. The court has a 6-3 conservative majority.

But some legal scholars theorize that interpreting “legislature” to mean only “legislature” could go too far even for some conservative members of the court.

Helen White and Cameron Kistler, writing in Election Law Blog, note that before Justice Amy Coney Barrett joined the court, she warned against using just the dictionary definition of the words in the Constitution to make law: “Justice Barrett has previously emphasized that written language ‘is a social construct’ that ‘cannot be understood out of context.’ ”

But conservatives are closer than they’ve ever been to making the law of the land a once-marginal legal theory that gives state politicians more, unchecked power over how elections are run — right as these legislatures come under extreme pressure to overturn legitimate election results.