Her body washed ashore in Connecticut. The search for her family began.

The only thing clear to police was it wouldn’t be easy to find the mystery woman’s family. If they could not, she would be yet another of the United States’ growing number of unclaimed bodies.

There is no national count of how many lives end this way, but a Washington Post investigation that included interviews with more than 100 local officials from Hawaii to Maine who handle uncollected bodies found there are tens of thousands a year.

It also found that “border bodies” — people who did not live within the borders of the state where they died — are the hardest to lay to rest.

Death comes with a lot of bureaucracy, and just moving a body over a state line typically requires a transit permit. A probate judge’s approval is often needed, too. Then there are often disputes over which jurisdiction should pay to move and bury an unclaimed body. It’s even more complicated when other countries are involved.

“Whatever happened to respect for the dead?” said Peter Stefan, a Massachusetts funeral director. “Who cares where someone is from? There is no system to help these people, and that allows everyone to find a reason to back away.”

An’s last hours

No matter how globalized the world has become, handling unclaimed bodies is a very local job in the United States. It has remained that way even though people increasingly die far from family and even their own home.

There are more than 40 million immigrants with legal status in the United States and about 11 million more with no documentation. That means it is not uncommon for local police officers to be searching for relatives who speak no English and live half a world away.

There are more than 12,000 police departments across the nation, half with fewer than 10 officers, and the task of locating the family of a person who dies alone usually falls first to them.

Medical examiners and coroners search, too, but police have the greatest access to databases that are especially crucial in tracking down out-of-state or foreign relatives.

Minutes after a homeless man spotted An’s body floating faceup near City Pier, New London police were on the scene. Over the next two weeks, more than a dozen law enforcement officers worked on her case. They pulled surveillance video to trace her last movements, checked government databases, looked into her out-of-state addresses and contacted Chinese authorities.

Though only the 38th-largest city in Connecticut, New London is a busy crossroads. Amtrak passengers traveling between New York and Boston stop there. Passenger ferries depart from the waterfront to Rhode Island’s Block Island and New York’s Fishers Island. The U.S. Coast Guard Academy is a local landmark.

Police didn’t know why An came to their city, but they learned how she arrived. Surveillance video captured her outside Foxwoods Resort Casino, 15 miles away, the evening before her body was found. She was walking toward a shuttle bus to New London.

A Foxwoods luggage claim tag in her backpack led police to her purple roller bag, left at the casino. Curiously, even though it was August, the bag contained winter clothes: a North Face fleece, Ugg boots and leather gloves.

While gambling, she avoided the bars and drank Dunkin’ Donuts coffee, Foxwoods’ security video showed. At one point, she talked on her iPhone as she walked among the slot machines.

Her iPhone held great promise, a potential gold mine of numbers that could lead police to someone who would bury her. But police could not turn on the waterlogged device.

A detective then slipped out the phone’s SIM card and saw that her service carrier was Lyca Mobile. He called the company, which advertises “the best international rates.”

A Lyca official told the detective that An’s phone records could probably be retrieved, but the company would need a court order. So the police officer drafted a request to a judge and waited for his supervisor to authorize sending it.

But no one did. Police closed the case after two weeks. Other cases needed attention. An investigator at the medical examiner’s office would have to continue to search for An’s next of kin.

As in so many places, New London police have been forced to deal with the opioid crisis and violent crime with fewer and fewer officers. In 15 years, its force had shrunk from 98 officers to 68.

Police Capt. Matthew Galante said a tremendous effort was made to find An’s family. “It’s important,” he said. “We want to go above and beyond. Just personally, I think, ‘What would I want if it was somebody in my family?’”

But he said crime victims want justice, and the burglary or assault calls keep coming.

Paul Belli, who investigates murders in Sacramento and is president of the International Homicide Investigators Association, said local law enforcement officials constantly must weigh the merits of cases like An’s, including their solvability, against other duties.

“It’s always a balancing act,” he said.

He personally would turn to his FBI contacts and also to the State Department if he had a case like An’s, he said. But many local officers do not have a relationship with federal authorities. There are no national guidelines for local authorities to follow in such cases.

Although the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security and the State Department could help, Belli said, “you can’t just drop the case on their plate and say, ‘Deal with this.’”

The morning after An’s body was found, an autopsy doctor in the state medical examiner’s office had concluded that she had drowned, but he said he could not determine whether she had fallen, jumped or been pushed into the water.

Before the autopsy, two New London police detectives had lifted inked fingerprints from her hands. It wasn’t easy.

“The surfaces of the fingers were irregular from the body being in water,” according to the police report. The detectives sent three sets of her prints to the FBI, hoping that federal databases might have her fingerprints and that a match could lead to a file with family contacts.

But the FBI said that “better quality prints would be needed for a positive association.” Usable prints can be taken from bodies that have been submerged in water for days, but fingerprint experts said many local police officers would not have the training and experience needed.

New London police did not take any more prints, saying new ones were “unobtainable.”

Repatriations of the dead

No one tracks exactly how many foreign nationals die each year in the United States, but it is many thousands. Mexico alone transported more than 7,600 bodies back to the country for burial in 2020, according to the Mexican government. U.S.-based diplomats from around the world say that repatriating bodies is a regular part of their workload.

Foreign diplomats have complained to the State Department about the hyperlocal way the United States handles the deaths of their citizens.

“Some find it insulting,” said a State Department official who was not authorized to speak publicly. “It’s been hard to explain to officials from other countries why some local cop is calling them, especially when they can’t even pronounce the name of the person they are looking for. When an American dies in their country, the national police handle it.”

Language often complicates the search for next of kin. For example, the State Department official said, imagine an Arizona police officer who speaks a few words of Spanish making calls to Mexico about someone who died and not understanding what is being said. Or a New Orleans detective not knowing that Chinese people write their family name first, so in a case like An Shun Jin’s, a detective might not realize he is searching for the An family.

‘The unclaimed, they never end’

An’s case frustrated everyone.

“We felt like there was family out there, but we just couldn’t find them,” said Holly Olko, an investigator in the Connecticut medical examiner’s office who continued to work on the case after police stopped. An was young enough that her parents were probably still alive. She had talked to someone on her phone.

With An’s body decomposing in the morgue two weeks after her death, Olko starting calling funeral homes to cremate or bury her. Her office had a list of those willing to bury the unclaimed for the state’s $1,350 reimbursement. That often doesn’t cover all the costs, let alone the time the bureaucratic process can involve, but it helps.

The first funeral home she contacted declined after talking, as required, to a probate judge to get permission to take control of the body. The judge raised the issue of An not being a resident of the state. That could mean no state reimbursement.

Olko tried another funeral home. And another and another. But no one would agree to bury An.

“Funeral homes are a business,” Olko said. “I get where they are coming from.”

She then tried funeral homes just over the border in Massachusetts. An’s Massachusetts driver’s license had expired in 2017 and listed an address near Boston University. But police could not find anyone at that apartment building who knew her, and the property manager told The Post she had no record of An ever living there. Massachusetts funeral directors contacted by Olko also declined to bury An, because they worried her ties to their state were tenuous and they would not get state aid to cover their costs.

Massachusetts pays funeral homes $1,100 for these cases, an amount that has not increased in nearly 40 years, leaving little incentive to handle the growing number of unclaimed bodies in the state.

It is cheaper to cremate a body than to bury it, and most localities choose cremation for the bodies no one comes to collect.

“Obviously something needs to be done, because she’s not the only case out there like this,” Olko said.

Every day for the past four years of her long career, she has handled unclaimed cases.

“The unclaimed, they never end,” she said. “No one wanted to take care of this poor woman. Nobody wanted to step up. That’s where the system fails the most.”

An’s story

During their investigation, New London police called the Chinese Consulate in New York. Officials there said they found an old address in China for her parents but could not contact them. (Reporters from The Post have been barred from visiting the address because of China’s coronavirus travel restrictions.)

Chinese officials told police nothing about who An was.

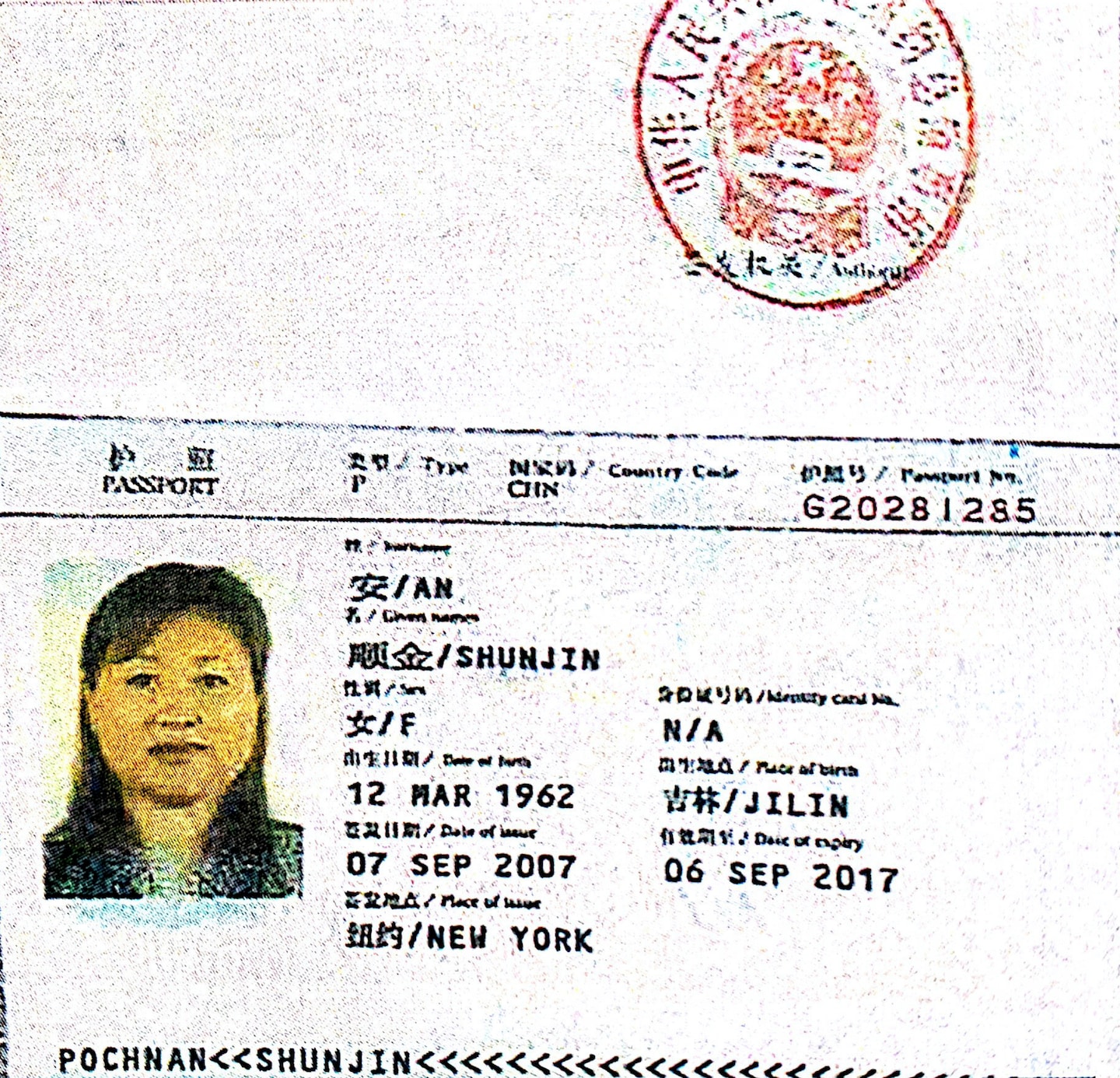

But documents obtained by The Post through a Freedom of Information Act request to the Department of Homeland Security helped fill in some details. The journey of the woman found wearing a “New York” T-shirt began in poverty 10,000 miles away.

She was born in Tumen, a Chinese city on the North Korean border where most people are of Korean descent.

Many struggled to get enough to eat when she was growing up there in the 1960s and 1970s. Weeks after she graduated from high school, she said goodbye to her parents and left for the promise of New York.

She crossed the Mexican border illegally, without a passport, to arrive in the United States on July 21, 1981 — when she was 19, she told U.S. immigration officials years later. Then she kept going 3,000 more miles, to Flushing, N.Y, 10 miles from Manhattan. Flushing has the feel of an Asian city, where Chinese and Korean are commonly spoken in shops selling Asian spices and food. An told immigration officials that when she arrived she worked in a Flushing nail salon and for eight years she earned $5 an hour. Her pay slowly climbed, and she said by 2005, after 24 years, she was earning $13.75 an hour.

In the early 1980s, when An arrived in the United States, smugglers were bringing boatloads of Chinese women across the often dangerously rough Pacific Ocean to Mexico and then walking them over the U.S. border.

The cost of admission was steep: $20,000 or more. It is not known how An paid her passage to the United States, but typically those who survived the journey were indebted and forced to pay back the smugglers with their new American wages.

Court records from New York show An was arrested on charges of prostitution and giving a massage without a license in 2008, but those charges were dismissed. An spoke Mandarin, and police needed a translator to talk to her.

The next year, police said, she gave a massage to an undercover officer in a spa in Hicksville, 20 miles from Flushing. She was charged with working without a license and given a court date.

An did not appear for her 2009 court hearing, triggering an arrest warrant. It was still outstanding when she died nine years later. She could have been jailed and deported if she had ever landed on police’s radar again, even for a traffic violation; there is no record of her ever doing so.

People who do not speak English or are without legal documents are more vulnerable to being exploited by human traffickers, who frequently force or coerce victims into the sex trade, nail shops or unlicensed massage businesses. In and around Flushing, police frequently raid those businesses in the name of stopping trafficking. But critics say those raids only make victims more vulnerable by leaving them with criminal records.

“Flushing is a gateway for human trafficking on the entire East Coast,” said Stephanie Simpson of Restore NYC, a group that supports victims of trafficking. She said the details of An’s life “raise all kinds of flags” that she could have been trafficked. “She doesn’t speak the language. She’s undocumented. She doesn’t have any other feasible economic opportunities. So she’s a very, very easy target in a way.”

Flushing, where An lived for most of the 37 years she was in the United States, is also a place where many are wary of strangers. When a Post reporter visited five addresses there linked to An in court or DHS files, most people who answered the door said they didn’t speak English.

A nail salon owner repeatedly said, “No English! No English!” — until she spoke it clearly. She said she had just bought the business and did not know “the poor woman you are talking about.”

One apartment where An shared a room was on busy Northern Boulevard, where a long line of people, many older and from China or South Korea, waited to get rice and vegetables from a food bank.

The man in charge of one apartment building’s maintenance looked intently at An’s photos and said it was “very possible she was one of the five females” crammed into a flat on third floor. “But turnover is crazy. They come. They go.”

A path to legal residency

An had once been on the cusp of becoming a legal U.S. resident. In late 2005, she filled out U.S. immigration applications to work and live legally in the United States. That would have given her more job opportunities, new legal rights and the freedom to leave the country to visit her relatives then return to the United States.

A law passed during the President Ronald Reagan’s administration opened a path to legal residency for those who entered the country before 1982. Nearly 3 million people used it. At the time, Reagan said the law would help those “who now must hide in the shadows, without access to many of the benefits of a free and open society.”

An filled out the application and, as required, showed proof of nine vaccinations, including for hepatitis B and the mumps. She arranged for her birth certificate to be sent from China, and she passed an FBI criminal-record check.

But on May 4, 2006, she didn’t show up for her interview on the ninth floor of the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building in Lower Manhattan. Not showing, without an explanation, was viewed as an abandonment of the case. “As such, your application is abandoned and is denied,” the letter from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services said. It said the decision was final.

Four years later, as a result of a class-action lawsuit, U.S. immigration officials said An and many others who had missed their interviews — often because their employers wouldn’t give them the time off — could appeal. They still had a chance at legal residence. But An never saw the 2010 letter sent to her with that news. It was returned unopened to federal immigration officials in Missouri. An, who was constantly moving to new shared rooms, had moved on yet again.

Just about every hour of every day, a bus leaves Flushing for the Foxwoods casino carrying passengers lured by the chance of hitting it big, a cheap bus ticket and a free buffet.

An spent her last night at Foxwoods, where security officers track betting activity. They told police An started out strong at a card table where she played mini baccarat for an hour and 27 minutes. She began with $500 and won $200 before she started losing. When she dropped $400 in 20 minutes, she called it quits.

While others around her ordered booze, security cameras showed her buying Dunkin’ Donuts coffee — the medical examiner later found no alcohol or drugs in her system. She left her luggage in the casino cloakroom and rode a bus to New London, arriving around 8 p.m.

An Amtrak employee saw her later that evening on the train platform, across the tracks from where her body would be found the next morning. Flags from around the world line the dock area.

‘If I didn’t go, no one would’

Two months after An died, Olko, in the Connecticut medical examiner’s office, heard about Stefan, the funeral director in Worcester, Mass, and called him.

Stefan, 84, was known for burying those others would not, including Tamerlan Tsarnaev, one of the Boston Marathon bombers.

He agreed to bury An. With the required body transit permit, Stefan’s co-worker L.W. Smith brought An’s body from Connecticut to Massachusetts.

Stefan also picked up a dozen other unclaimed bodies around the same time, including homeless people with no money or known relatives.

“Police call me from Boston, Framingham, Hudson, from all over,” he said. “They say, ‘I’ve been sitting with this body for eight or nine hours, and no one will pick up it up.’ They beg me to help. If I didn’t go, no one would.”

Stefan said government officials have not paid enough attention to the problem of unclaimed bodies.

“Any dummy knows that there is a problem when the state hasn’t raised the fee they give for these cases in 39 years,” he said. “The system is broken. No one is looking at it. Maybe it would be different if the dead could vote.”

In early 2019, as An’s body lay in Stefan’s funeral home, new state laws had just passed to shield those involved in cremating unclaimed bodies from any lawsuit filed by a relative who surfaced later. But his city’s regulation did not immediately take effect.

Stefan said he had not anticipated that lag time and had accepted too many unclaimed bodies. With his cooler full, he stored some of them, including An’s, in the air-conditioned basement. After neighbors complained of odors, the city suspended his license, before later restoring it.

Laid to rest

Fourteen months after An’s body was found in New London, she was buried in St. John’s Cemetery in Worcester on Nov. 1, 2019, a day Christians celebrate as All Saints’ Day.

Stefan said he paid for the casket, transportation and other expenses, with no state reimbursement. Smith, from Stefan’s funeral home, said prayers over her light blue casket as it was lowered into an unmarked grave.

Smith was sure An had loved someone and someone had loved her. But no one who knew her was there as he stood in a cold autumn wind and said, “My dear sister, I lay you to rest.”

Alice Crites contributed to this report.