Biden and the fraught history of presidents promising no war

Reagan quickly sought to correct the record. He assured that he had made no such open-ended promise. “Well, presidents never say ‘never,’ ” he said, later repeating: “It’s an old saying that presidents should never say never. You know, they blew up the Maine. But, no, I see no need for it.”

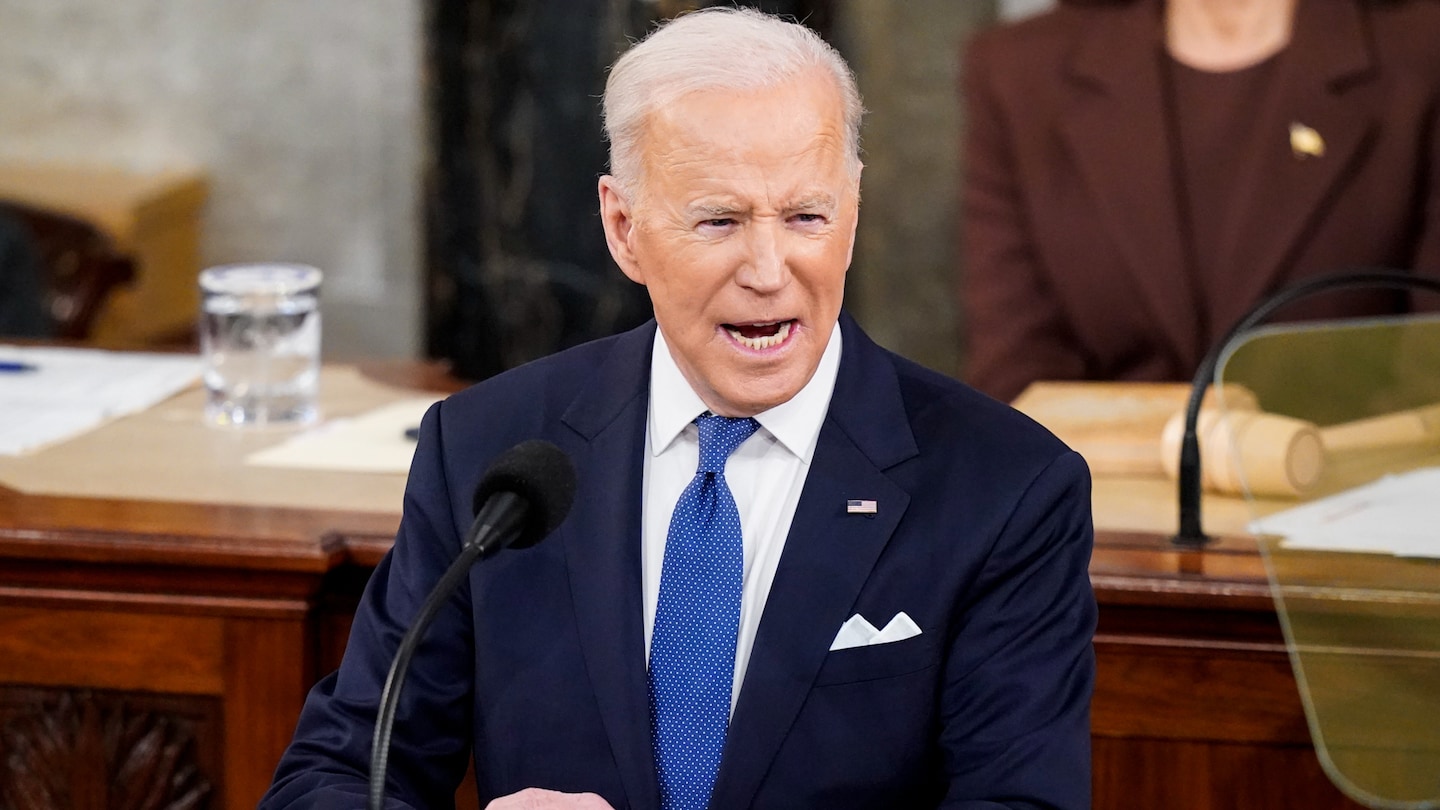

In fact, presidents do and have said something amounting to “never” about going to war. And despite the decidedly checkered history of such promises — and very valid questions about the wisdom of such a posture — it’s happening again. President Biden has repeatedly assured in recent weeks that the United States will not send troops to Ukraine. Biden and the White House have reiterated the promise even as evidence of Russian war crimes increases and the possibility of Russia suddenly being on NATO’s doorstep looms.

The promises have carried varying degrees of firmness. But they have marked some of the biggest wars in U.S. history.

In 1940, the Democratic Party platform declared, amid the rise of another world war across the Atlantic: “We will not participate in foreign wars, and we will not send our army, naval or air forces to fight in foreign lands outside of the Americas, except in case of attack.” Franklin Delano Roosevelt added, “I have said this before, but I shall say it again, and again and again: Your boys are not going to be sent into any foreign wars.” The following year, the bombing of Pearl Harbor again pushed the United States into a war it had studiously sought to avoid.

Of the trio, Johnson’s pledge was the most objectively broken. Wilson’s slogan was more about what he had done up to that point, and he could credibly point to German aggression as forcing his hand. FDR’s pledge, meanwhile, frequently carried the caveat of “except in case of attack,” which Pearl Harbor certainly triggered.

“There’s really good precedent for a president saying he would not send our foreign troops to fight … and then things change,” said presidential historian Jeffrey A. Engel. “Indeed, I would not say either [Wilson or FDR] lied to the American people, as both strongly desired to keep us from the actual fight.

“Yet, as so often happens not only in global affairs but in times of war … the other side got a vote too.”

It’s against this backdrop that Reagan in 1983 made his “never say never” comments. But despite that, presidents have continued saying never in even more caveat-free ways.

Obama also repeatedly assured there would be no American “boots on the ground” in Syria, before sending in a small number of Special Operations forces in 2015. (The White House argued that Obama’s pledge was only about combat troops, but Obama’s early statements had drawn no such distinction.)

Even Trump’s comment, of course, carried an “unless … absolutely necessary” caveat, which people can decide for themselves whether the situation in Syria satisfied.

Biden’s posture, though, is both firmer than almost all of the above and more substantial than the more recent pledges, given the stakes of the war in Ukraine. Before the invasion, he layered it with some wiggle room, saying there were no “plans” to go to war and no “intention” to send troops. And those words have continued to crop up from time to time, including in recent days. But he and the White House have also been firmer:

- Biden in January: “There is not going to be any American forces moving into Ukraine.”

- Biden on Feb. 18: “We also will not send troops in to fight in Ukraine.”

- White House press secretary Jen Psaki on Feb. 23: “That is not a decision the president is going to make. … We are not going to be in a war with Russia or putting military troops on the ground in Ukraine fighting Russia.”

- Biden on Feb. 24: “Our forces are not and will not be engaged in a conflict with Russia in Ukraine.”

- Psaki on March 7: “We are not going to send U.S. troops to fight in Ukraine against Russia. The president is not going to do that.”

While many of these comments were off the cuff, Biden also inserted this pledge into his State of the Union address on March 1. “But let me be clear,” he said. “Our forces are not engaged and will not engage in the conflict with Russian forces in Ukraine.”

What happens if evidence of Russian war crimes increases or it uses chemical weapons? What happens if it becomes clear Russia has no intention of stopping at Ukraine’s (and NATO’s border)? It doesn’t mean you have to make direct threats, but there’s something to be said for strategic ambiguity — i.e. avoiding declaring red lines but having your adversary believe any escalations might cross one.

The White House has chosen to err on the side of calming fears about the prospect of another world war, with Biden increasingly addressing that very prospect explicitly. He said Friday that “we will not fight the third World War in Ukraine.”

If the history of those world wars is any indication, circumstances have a way of putting such declarations to the test.