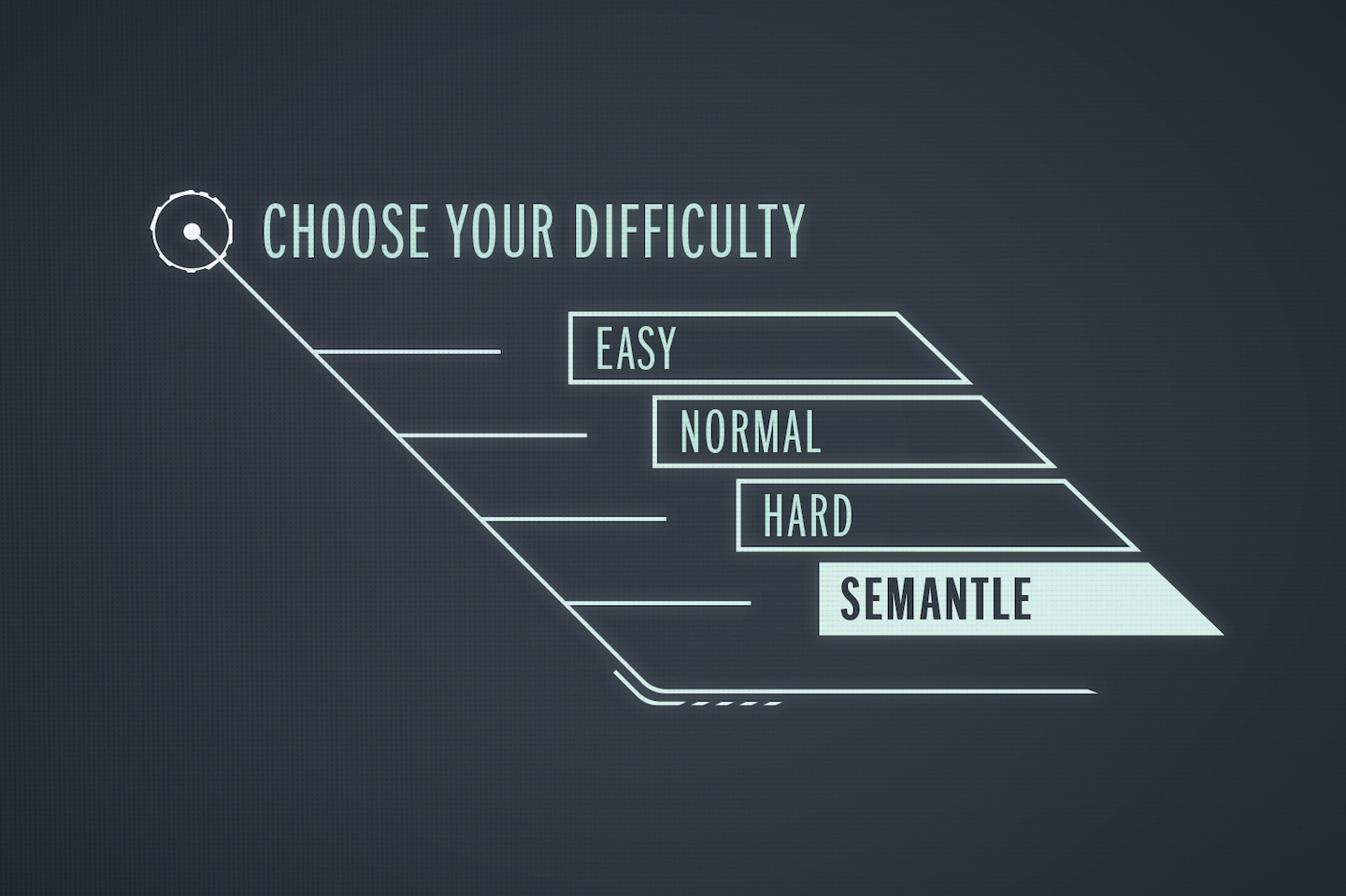

Semantle is like the Dark Souls of Wordle

Conjured up in a few hours by 41-year-old New Yorker, David Turner, Semantle went live on Feb. 27 and is the product of what happens when Wordle’s difficulty knob is turned so forcefully to “Hard” that it snaps off in a cartoonlike manner.

“It’s so weird. It’s so hard. It’s, like, beyond anything that you think people should be able to do,” Turner said in an interview with The Washington Post.

Whereas Wordle’s bright colors, refined user interface, relatively short learning curve and multiplatform accessibility create a welcoming environment for players young and old, Semantle’s experience is anything but.

While the concept of guessing the “correct” word is similar, Semantle’s answer can be any number of letters long. The only way a player knows if their guess is on the right path is through Word2Vec, the Google-owned, underlying technology running the game, which produces a number representing how close the word’s meaning is (a.k.a. how close it is semantically — hence the name) to the solution based on the platform’s understanding of language. It also provides a “Getting close?” indicator of “hot” or “cold.”

Upon firing up Semantle for the first time, players are met with a wall of text explaining the rules, a similarity score that represents how close, contextually, the algorithm deems your guess is to that day’s secret word and an endless number of possible wrong answers that can crush your confidence shortly after it begins to sprout.

According to Semantle’s rules, if a player’s guess is one of the nearest 1,000 normal words to the target, it’s given a rank. If not, you’re “cold.” As the game’s instructions explain, “normal” here means non-capitalized and non-hyphenated words in the extensive list of English words Semantle references to randomly select its daily solution.

For example, guessing “bright” on Tuesday, March 29’s puzzle gives you a similarity score of 19.28, and its polar opposite, “dark,” yields 8.78. Helpful, but there’s still myriad ways players can interpret that information. For this puzzle, which resets at midnight each day, players needed a word with a similarity score of 74.86, which could be found in the word “skyrocket,” to represent the word most like the solution: “soar.”

Funnily enough, the plural version of the solution “soars” is actually the third closest word to the answer (997/1000), according to the algorithm. How diabolical.

To understand the complexity behind the game is to understand its creator.

Turner is a programmer with a background in software development who currently works at a cryptocurrency company and enjoys spending his free time trying to stimulate his mind with challenges.

Turner, who said one of his pastimes includes creating and playing his own games, recalls lying awake one night and brainstorming a way to improve upon Wordle’s relatively simplistic design.

“So in Wordle, every position has 26 possibilities, which is not very many,” Turner explained. “I began to think ‘What else has a small number?’ And I remembered Word2Vec.”

Google describes Word2Vec as a tool that “takes a text corpus as input and produces the word vectors as output. It first constructs a vocabulary from the training text data and then learns vector representation of words.”

As those vectors only use a few hundred dimensions to identify a word, it was small enough to do the job.

Turner combined his skills in coding, love for game design and inspiration from Wordle to create Semantle. It only took him a few hours of programming, and the game was done.

Looking for feedback on his latest game design, Turner sent Semantle to a few of his friends. One “didn’t find it playable,” he said, but sought further input and shared it with members of their online communities without Turner’s express permission.

“Then it was out there,” Turner says now, with a laugh, after the initial surprise wore off.

Less than two months later, the game has soared in popularity.

According to Turner, who said he is too busy to play Semantle himself, nearly 200,000 individuals sign on to play each day’s puzzle, and that figure continues to grow.

Despite the difficult and “deeply unfair” nature of the game at times, Turner says he’s received a horde of emails from individuals who use Semantle as a team-building exercise, a way to bond as a family and even as a way to learn the English language.

Turner also finds the way players talk about the game intriguing. He notes that those who enjoy Wordle often share their scores online to show how smart they are, but Semantle acts more as a journey for many.

“[Players] are not going to brag to their friends if it takes them 300 guesses … what they’re bragging about now is something different,” Turner said. “They’re not bragging that they’re so smart. They’re bragging that this day, [they] persevered and stuck at it until they did this very difficult task.”

C. Thi Nguyen, associate professor of philosophy at the University of Utah, studies the social epistemology, aesthetics and philosophy of games and understands the levels of variance in those who play them.

“There’s a massive audience for extremely simple, chill and casual games, and then a massive audience for grueling, really difficult games, right? I mean, you have ‘Candy Crush’ on one side, and you have the Dark Souls [franchise] on the other,” Nguyen said.

Considering the level of difficulty involved in Semantle, players often share their frustration or exhaustion trying to solve the daily puzzle on social media forums like Reddit, then share that they cannot wait until the next day’s challenge.

One such user on the game’s subreddit summed up their relationship with Semantle as: “I’ve explained this game to people, explicitly [do] not recommend it, and yet play it every day,” said one Reddit user.

“I think a mistake a lot of people make is that people are interested in the game for the achievement of winning. And I think there are two actually very different motivational stances people make,” Nguyen said. “Some people want to win, and some people try to win because they like being caught in the struggle.”

One quick search of the game on social media will yield cries for help, dozens (if not hundreds) of guesses before solving the puzzle, and players supporting one another while sharing their own grueling journey to a solution (or forfeiture).

“One way you can tell the second population is if a game is too easy, they get bored of it,” Nguyen said. “They want to be caught in that hard struggle. So I think for a lot of people that the winning is actually just on the side. What you want is the deliciousness of the struggle.”

Tim Rizzo is a freelance journalist who has over a decade’s worth of experience in the news industry. He can be found at @TimRizzo on Twitter.