The Trump presidency and its aftermath have led our politics to yet another apparently unprecedented place: A House committee subpoenaing its own colleagues for testimony.

Jan. 6 panel’s historic subpoenas to House GOPers — and what’s next

So how likely are we to ever see McCarthy and the rest actually testify?

Precisely what happens next is anyone’s guess, thanks to what we mentioned at the top — the lack of precedent. But it’s worth reviewing the few analogous situations we have, along with the practical and strategic considerations for the Jan. 6 committee.

About the closest comparison to this situation came in the early 1990s, when the Senate Ethics Committee subpoenaed Sen. Bob Packwood (R-Ore.) for his personal diaries amid a sexual harassment inquiry. Packwood fought the subpoena all the way to the Supreme Court but lost. He ultimately resigned after the committee issued its report and he faced expulsion.

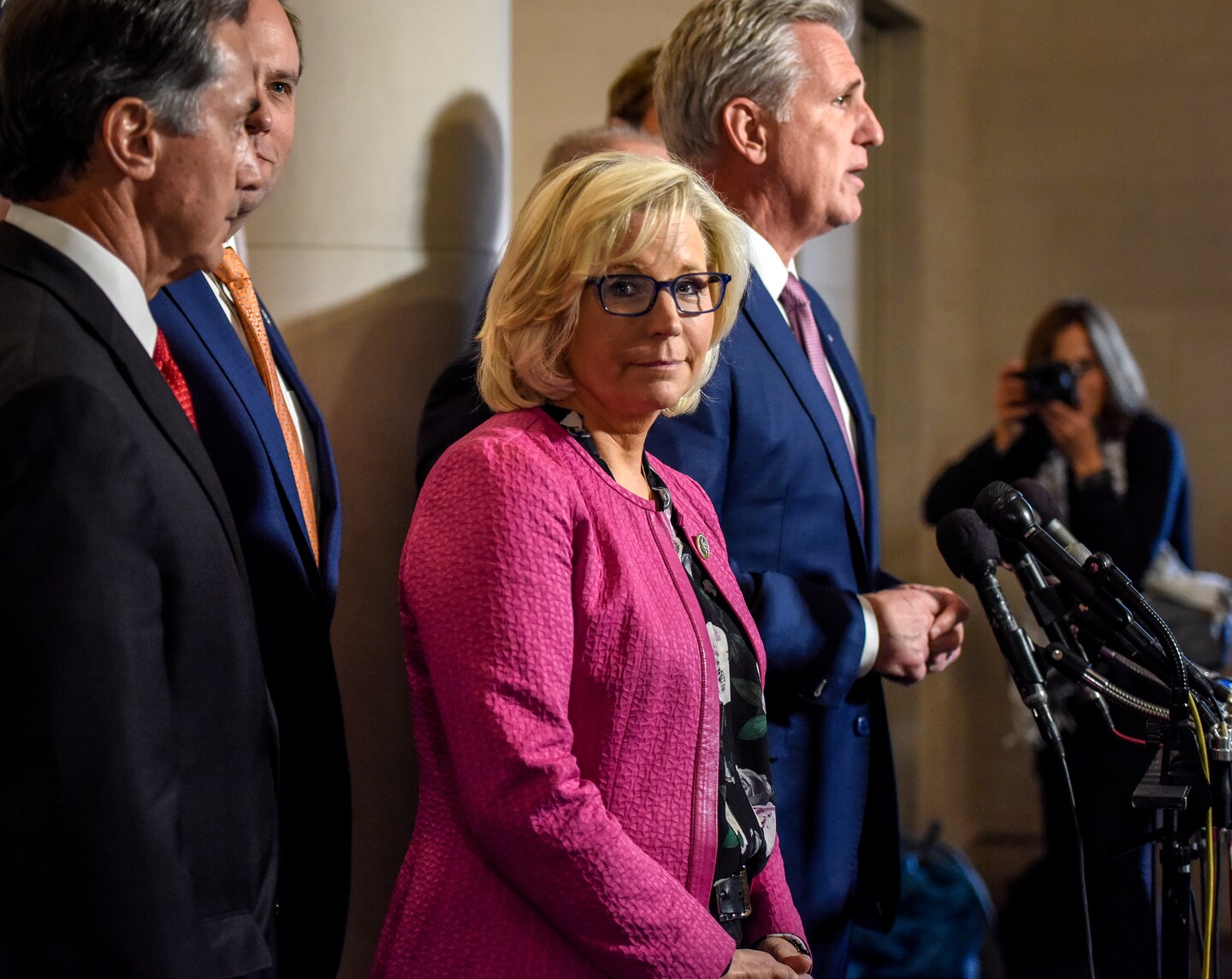

A key difference between Packwood’s situation and those of McCarthy and his colleagues — Reps. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), Scott Perry (R-Pa.), Mo Brooks (R-Ala.) and Andy Biggs (R-Ariz.) — is the committee making the request and its stated purpose. The courts have routinely acknowledged ethics committees’ power to police and discipline members, but the Jan. 6 committee is investigating the insurrection, not specific members of Congress themselves.

(That said, perhaps in preparation for the upcoming legal battles, the committee has hinted at an interest in potential wrongdoing by the subpoenaed members related to Jan. 6 and trying to overturn the election more broadly.)

Setting aside the question of who would win a legal fight over the committee’s powers, there’s the method for how it gets resolved. Generally speaking, there are three legal options on the table and a fourth administrative option for the House if the members resist the subpoenas, as expected:

- Refer members who defy subpoenas to the Justice Department for criminal prosecution.

- Go to civil court to compel the testimony.

- Have the sergeant-at-arms arrest and detain the member.

- Punish the member through fines or by stripping them of committee assignments.

Option No. 3 would seem highly unlikely, given how punitive it is and the fact that it hasn’t been used in nearly a century — and even then, not against a member of Congress. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) broached the subject during a showdown with President Donald Trump’s then-Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin in 2019, but apparently in a joking tone.

Beyond that, it’s not clear which would be the most fruitful course — or, more specifically, which action has the best chances of success given the committee’s tight time frame.

The committee has repeatedly invoked Option No. 1 — referrals for criminal prosecution — on other witnesses who have defied subpoenas: top Trump White House aides Stephen K. Bannon, Mark Meadows, Peter Navarro and Dan Scavino. Bannon, the first to be referred to DOJ, was later indicted on charges of contempt of Congress in November, but the trial won’t begin until July — after the committee’s planned public hearings.

Such a time frame wouldn’t seem viable for a committee that aims to produce its report before the 2022 midterm elections. And it seems likely DOJ wouldn’t be as willing to indict sitting members of Congress. After all, after five months the DOJ has yet to indict Meadows, whose case presents tougher questions about whether his testimony might be privileged than Bannon’s did. (Navarro’s and Scavino’s referrals came just last month.)

If anything, pursuing Option No. 1 would seem aimed at compelling the members to give up resisting the subpoenas, for fear of possible indictments. But it would be a gamble given the lack of a Meadows indictment — and given that they could, conceivably, just try to run out the clock. That path would also require a majority vote from the House, which the committee has gotten on the other occasions but might be a tougher proposition when members are facing their colleagues.

Option No. 2 — going to civil court — would pose some of the same practical barriers as Option No. 1, especially when it comes to the time frame. The House spent two years trying to get Trump White House counsel Donald McGahn’s testimony for the Russia investigation. And when it finally obtained that testimony, it was anti-climactic; it came after the investigations were over, and McGahn said he had forgotten plenty in the meantime.

There’s also the distinct possibility, as with Option No. 1, that you won’t ultimately get what you want. The uncertainty here is huge, given the untested nature of subpoenaing members of Congress and the protections offered by speech or debate clause, as Kimberly Wehle wrote in the Atlantic and Tanner Larkin and Andrew Nell wrote recently for Lawfare.

That Lawfare piece and another from last week suggest, then, that Option No. 4 might be the best and most readily available one for compelling testimony. University of Chicago law professor Albert W. Alschuler writes:

Better still would be daily fines, which could escalate for every day or week of noncompliance. One judge doubts that resurrecting the use of Congress’s inherent power to sanction contempt remains a realistic option. He worries that Congress would risk “physical combat with the Executive Branch” by “dispatch[ing] the Sergeant-at-Arms to arrest and imprison an Executive Branch official.” But ordering a contemnor to pay a fine to the sergeant at arms for every day of noncompliance would be unlikely to lead to a shootout.

A House resolution imposing this fine could authorize the sergeant to use all available civil processes to collect it. The contemnor could challenge the legality of Congress’s action by bringing an injunctive action against this officer. She also could take the riskier path of waiting to present her defenses until the House sought recovery of her accumulated fines in a civil lawsuit. If the contemnor refused to pay after a court ordered her to do so, the House could use the same collection procedures other judgment creditors employ — for example, garnishing the contemnor’s wages. Guns, handcuffs and hotel rooms wouldn’t be needed.

Again, there would be questions about just how comfortable even House Democratic lawmakers would be with this precedent. Republicans have shown no shortage of appetite for investigating matters such as Benghazi to the hilt. They’ve also repeatedly and expressly threatened retributionfor Jan. 6-related inquiries and disciplinary matters used against the likes of Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.). The message has been clear: Turnabout will be fair play — however comparable future situations might actually be to an attempt to subvert democracy.

House Majority Leader Steny H. Hoyer (D-Md.) weighed in on that Thursday after the subpoenas were announced, effectively telling Republicans to bring it on. “If they want to subpoena me at some point in the future, I will go in and I will tell the truth,” Hoyer said. But even if Hoyer truly feels that way, being put under oath is not a fun experience.

Indeed, even going as far as issuing subpoenas to its colleagues is a big escalation for the Jan. 6 committee. We probably shouldn’t expect to see testimony from McCarthy and his colleagues any time soon, or at all, but the committee has now shown more investment in trying to make it happen — and dealing with everything that could come with that path.

Now we find out how serious the committee is about trying to enforce the subpoenas, and how vital it considers this testimony.