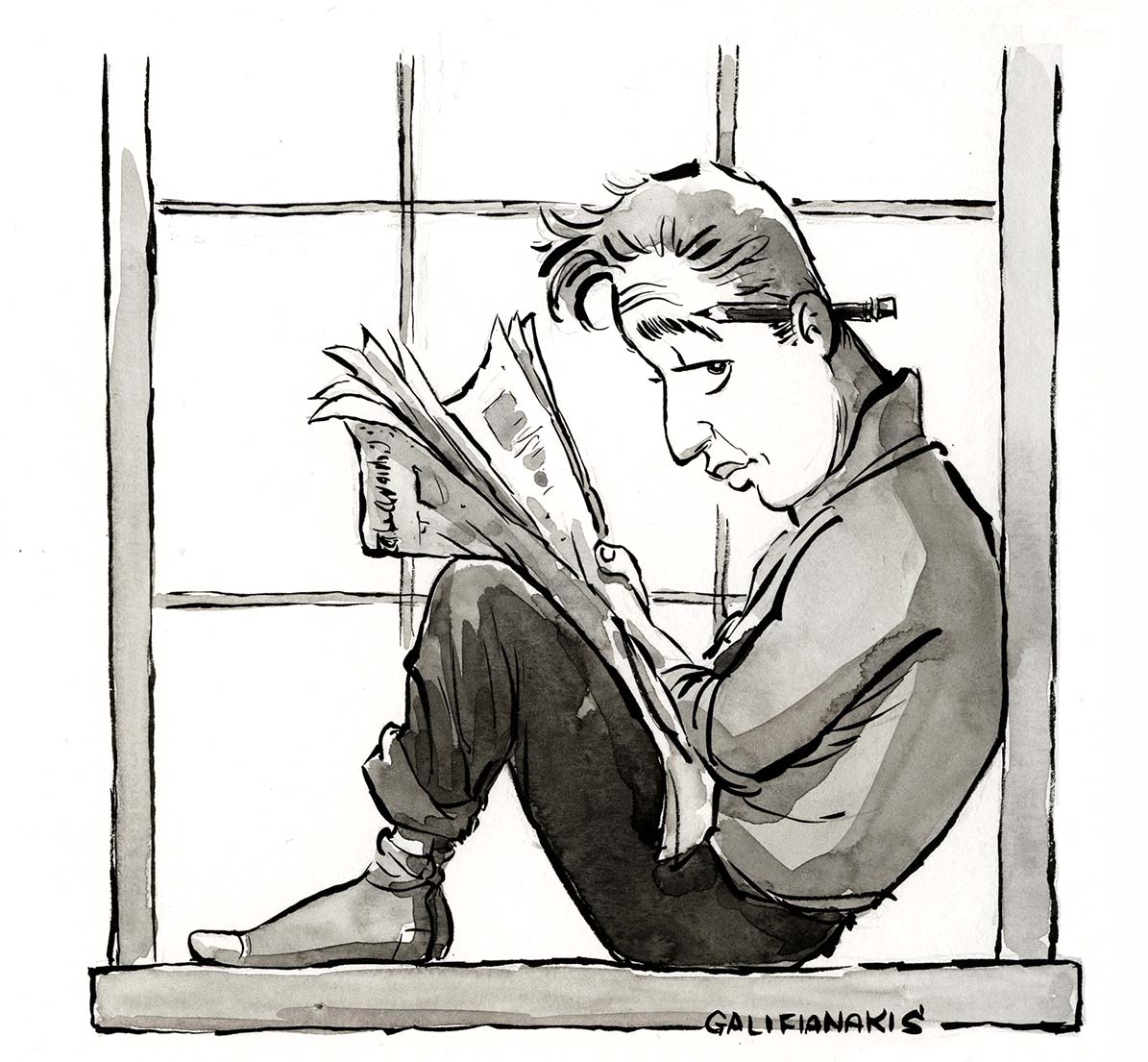

Hax cartoonist Nick Galifianakis reflects on 25 years of advice as art

After thousands of drawings for Carolyn Hax’s advice column, Galifianakis looks back on illustrating the human experience.

Warning: This graphic requires JavaScript. Please enable JavaScript for the best experience.

The cartoons started with a passing thought:

“…And maybe Nick could draw an icon to go with it,” an editor suggested to Carolyn Hax, my wife at the time, as they were discussing Carolyn’s new advice column in The Washington Post.

A quarter-century later, I have yet to draw an “icon” to go with the column.

The original idea was that I would create five, maybe seven, general images that would rotate through the column depending on the subject: breakups, weddings, family, etc. I was excited for Carolyn’s opportunity and wanted to do whatever I could to help its success.

But somewhere inside me was also a 5-year-old boy, eviscerating a half-foot thick Sunday Washington Post to get at the explosively colorful middle, spreading the giant comics pages on the floor, reading from the first cartoon to the last before breaking out crayon and paper to copy my favorite characters.

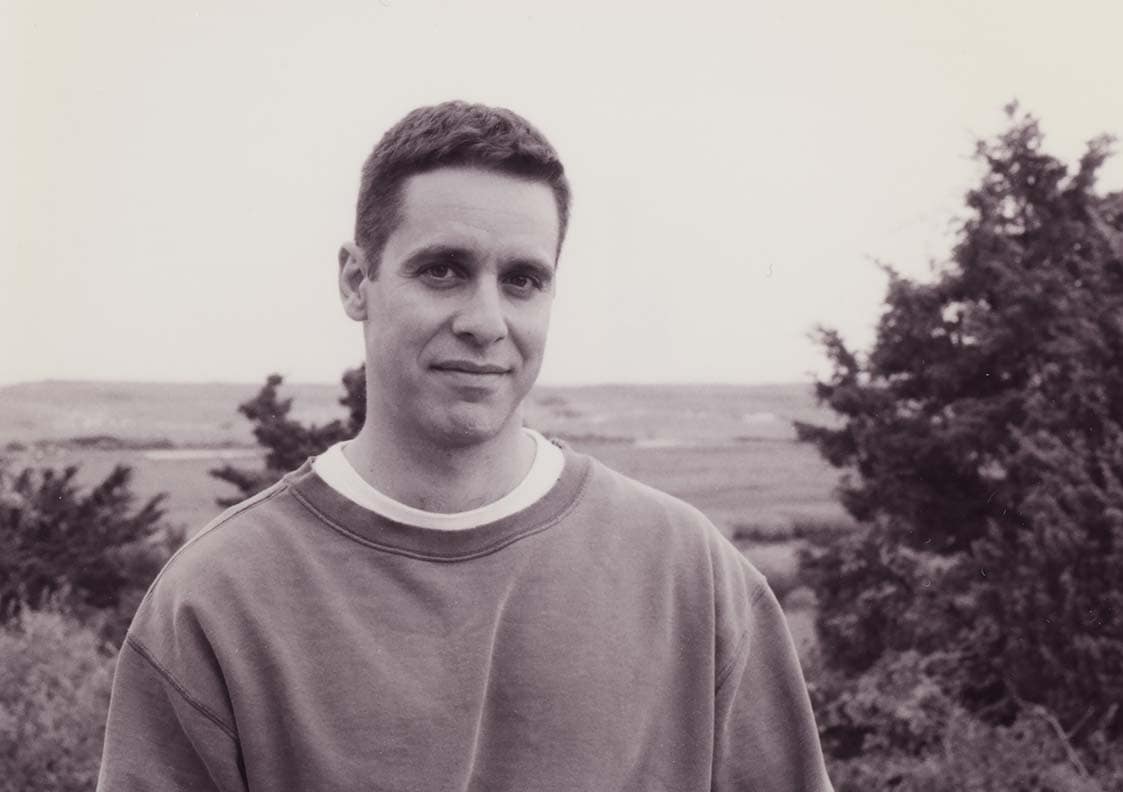

Nick Galifianakis: “Sitting at a keyboard, or drawing table or with a guitar and thinking, ‘What will people like?,’ instead of, ‘What do I like?,’ is how bad sitcom television is made. I think by answering the second question, you also nail the first one.”(Carolyn Hax)

So, sure, Carolyn, I’ll draw a handful of funny characters for The Washington Post.

And then I suppose a conspiracy of enthusiasm and ego hijacked my pen: I turned in a fully realized, captioned cartoon instead that was not only specific to that particular column but also stood alone.

Our editor liked it and built the print page around the column and cartoon. The response was good, and decades after my hiring for a fun side gig I never actually completed, I find myself with a career.

The first comic.

After that initial burst, Carolyn and I developed an approach that still stands: She chooses the letters and writes a draft, then sends it to me to edit and offer suggestions; she polishes it and we repeat until we both like it.

Then we switch hats and I ruminate over which angle to take with the cartoon, send her a bunch of concepts, and we run ideas back and forth until one of us laughs.

The concept has to add to the conversation in the column, not merely parrot it, and it must also stand by itself. If the cartoon only makes sense if you read the column first, then it’s a no-go. We both have veto power.

From the start, when we were married,

on through separation, divorce, remarriage,

kids and personal roller coasters,

we’ve maintained a strong working relationship.

We kept what was best between us so our collaboration, like our friendship, is built on trust, respect, the shorthand of familiarity, shared values and worldview.

So far, it seems to have worked. The best part of the whole transaction is hearing from readers who have been helped by the column and cartoons. That’s rocket fuel for returning to our desk and drawing board and doing the best work we can.

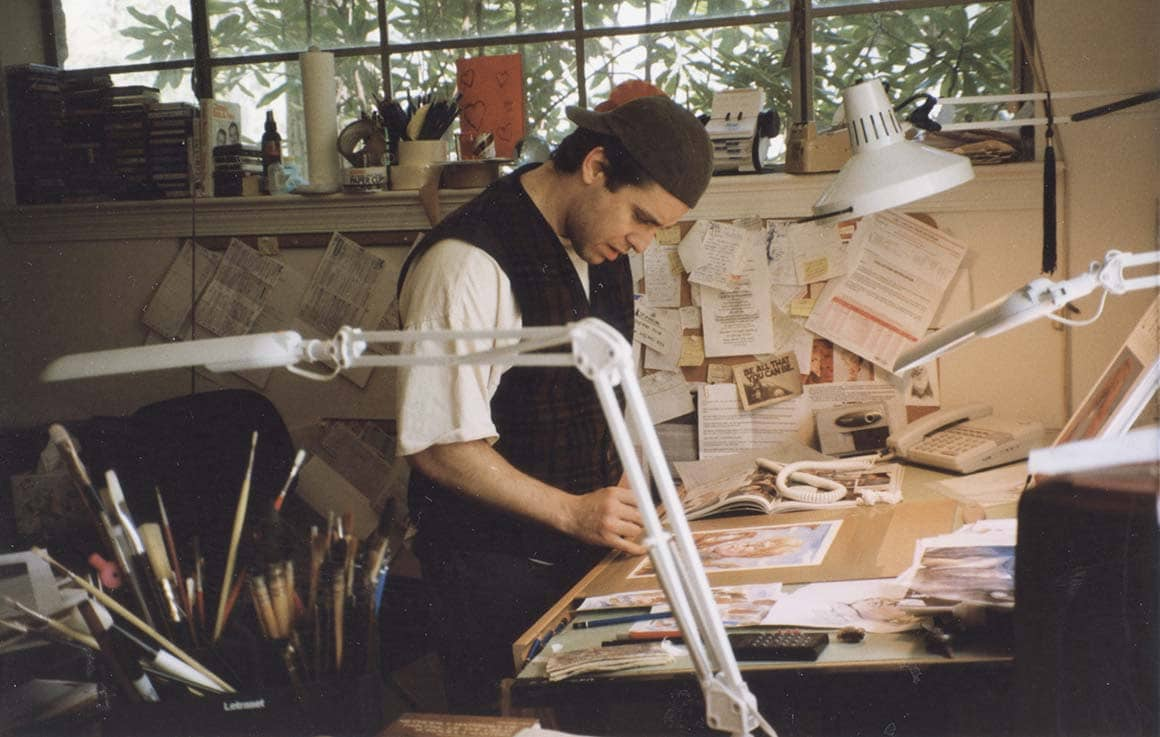

Any sustained effort, let alone one that lasts a quarter of a century, comes with growing pains and eye-openings. Most of my “aha!” moments as an artist have happened, gradually, daily, in the space The Post afforded me.

It became my art school:

From using a pen dipped in an ink well, then trying to find a sexier line by dipping a brush,

then falling in love with charcoal because I admired a cartoonist hero’s velvety line work, then aiming to harness the unpredictability of watercolor,

then combining all of the above;

then moving to the digital tools I use today for speed and expediency and digital compatibility; and always (always, always) discovering and rediscovering the value of “just enough is more” (more accurate than the tired “less is more”).

I was on an Amtrak once years ago, and watched two passengers sitting in front of me flip through the Style section.

“What a beautiful drawing,” said one woman right after turning to the page where the column and cartoon appeared. Added her friend: “The level of detail!”

And I was crestfallen. The passengers never commented on the cartoon’s gag; I don’t think they ever saw it. My obsessively rendered drawing had obliterated the joke. And that’s a bad cartoon. But, you have to recognize you’ll make a lot of bad cartoons before you make any good ones.

“Someone’s infidelity or jealousy or boundary-crashing or name-your-insecurity isn’t really the pull for me. But using cartoons to analyze an issue, and make it relatable, is endlessly interesting to me. And the single-panel cartoon offers a fun creative challenge: find the right moment to make that point, a slice of life that, whether they’re conscious of it or not, encourages the reader to consider what came immediately before and what will happen immediately after that moment.” (Carolyn Hax)

I used to populate the cartoons with people I know or even just the folks sitting around where I happened to be drawing. I would also dress the characters according to whatever the weather was at the time. The cartoons are about something real, even if the reality is stretched to the ridiculous.

I eventually (mostly) dropped the likenesses of family and friends and surrounding folks, because enough people kept asking, “Who is that?”

Which became a hurdle to allowing the caption and cartoon to mesh as intended.

Though I still occasionally include some familiar faces, including my own, today my characters are more generic, but they still, I hope, feel like individuals within your world.

I’ve always included people of varied backgrounds and sizes in my cartoons and Carolyn’s writing is unimpeachable on themes of race and inclusion. That is our world (yours too) and we reflect it. But including people of color in cartoons about issues that weren’t specifically about race was not terribly common in the late ‘90s. Years ago, when I made political cartoons, I might draw something on, say, the economy or budget, showing a Black person and a White person in suits carrying briefcases. And then the mail would start, “What does this have to do with affirmative action?” Nothing. They were just two people.

This challenged me to find situations that were inclusive and allowed people of color just to be people, not statements.

Because cartoons featuring people of color historically were exaggerated and insensitive, I was cautious and kept non-White and ethnic faces closer to slightly tweaked portraits. Eventually I convinced myself that if I drew in a fun and affectionate way, that would come through as a celebration of all shapes and features. So I just committed to drawing people. All of them.

The captionless “Chaxies,” cartoons accompany the column on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, and are named after Carolyn, (“C.Hax”).

They’re drawn in a different style because I based them on Post-it notes Carolyn used to leave around the house for me when we were married.

Her doodles still make me laugh.

I’ve never liked the look of most digital art. It’s often too slick, too antiseptic, too dependent on a powerful tool, instead of being an extension of the artist wielding it. So it took a while for me to embrace digital tools.

But the desire to produce artwork faster, and a commitment to retaining an analog look that feels like it came from me and not the computer, nudged me to make the leap.

And for that 5-year-old artist, who learned to read and draw from his local newspaper, producing thousands of cartoons for that paper over 25 years remains the professional privilege of his life.