“Joe [Manchin] cracked under pressure. Now he’s supporting Biden’s devastating plan to strip $300 billion from Medicare, leaving West Virginia seniors with even fewer treatments and cures.”

Ad targeting Manchin on prescription drugs uses misleading math

The group is not required to disclose its donors but it has received substantial funds from organizations linked to the billionaire Koch family, according to a recent review of tax filings by the Center for Responsive Politics. (The organization says it has not received any contributions of anyone in the Koch network for well over a decade.) AARP attacked the group in 2003 as a “front” for the pharmaceutical industry, but there appears to be little evidence of drug-company donations since then.

Let’s explore.

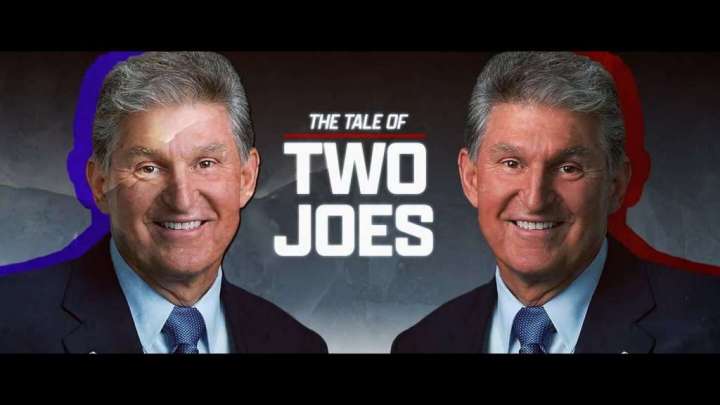

Manchin is the most conservative Democrat in the Senate. The ad is framed around the idea that there are “two Joes” — one who “did the right thing for West Virginia by standing up and blocking Biden and Pelosi’s liberal agenda” and another who supposedly switched positions and is now backing a plan to harm senior citizens.

The ad is too brief to get into much detail but it has two key points — one that Manchin would now “strip $300 billion from Medicare” and that this will result in “fewer treatments and cures.”

This rhetoric concerns a complex issue — prescription drug provisions contained in President Biden’s Build Back Better plan. Manchin blocked passage of Build Back Better earlier this year but has restarted negotiations with the Biden administration that may result in a new version being passed in the Senate. In any case, Manchin long has been a supporter of legislation that would allow the government to negotiate prices for prescription drugs.

The debate revolves around something called the “noninterference clause.”

When Part D of the Medicare program, which helps pay for prescription drugs, was created under President George W. Bush, lawmakers included a provision that prevents the federal government from having a direct role in negotiating or setting the prices for drugs in Medicare Part D, which are offered through pharmacies via private health plans. The prices currently are negotiated between manufacturers, private health plans, and pharmacies.

Many Democrats have never been happy with the noninterference provision and have long sought to repeal it. The theory is that if the health and human services secretary were given the authority to directly negotiate drug prices, it could help bring down the cost of drugs, especially newer, high-priced medications.

The version of Build Back Better that passed in the House would provide a limited exemption to the noninterference clause and empower the HHS secretary to negotiate prices for selected drugs — 10 starting in 2025, with the number growing to 20 over time — that have little competition and account for substantial spending. The drugs would be selected only after their market exclusivity period ends. In theory, government negotiation — which would take two years with manufacturers — would be limited to a subset of drugs that don’t have generic alternatives.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, this provision would reduce government spending by about $80 billion from 2022 to 2031, a ten-year period. That’s because some drugs would be less expensive and the government would have to pay less to subsidize pharmaceutical companies. Consumers would also presumably experience lower costs.

So why does the ad say Build Back Better would strip $300 billion from Medicare?

Saulius “Saul” Anuzis, president of 60 Plus, said the ad was referring to a CBO estimate that all of the drug-policy proposals would reduce the federal budget deficit by $297 billion over ten years. “It’s completely accurate to describe this as ‘strip[ping]” $300 billion from Medicare’ — as these are federal dollars that under current law would be dedicated toward Medicare outlays for seniors, but that won’t be dedicated to Medicare under the proposed legislation,” he wrote in an email. He even quoted from one of our previous fact checks — that reductions in spending “need to be measured against a current-services baseline in order to measure the potential impact.”

First, some context: $300 billion is just two percent of the nearly $12 trillion that CBO estimates that Medicare will spend in that ten-year period. It sounds like a lot of money by itself — and it is — but it represents a relatively small part of the overall budget.

It’s also a lot of Washington funny money. About half of the savings comes from not implementing a Trump administration rule that would have replaced protections for drug rebates in Medicare Part D with protections for discounts provided directly to consumers. That would have cost the federal government $145 billion over ten years. Since the regulation will not be implemented, the government “saves” $145 billion.

Imagine you had budgeted $145 next year to buy a hat, but decided not to do so. So suddenly you have $145 in savings to spend on something else. It’s not like you are “stripping” $145 from your family budget.

Anuzis conceded that “it is a bit odd to speak of pocketing ‘savings’ by ending a program that isn’t yet in effect.” But he said “Congress plays these budgetary games all the time” and that “the wording in our ad is correct in both letter and spirit.”

Others disagreed. Not all reductions to the baseline are cuts in spending. Juliette Cubanski, deputy director of the program on Medicare policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, said “it may be stretching the facts a little too far to characterize the $300 billion in savings from lower prescription drug prices as a $300 billion cut to Medicare.”

Cubanski said the “higher spending that we would have seen associated with implementation of the Trump Administration’s rebate rule wouldn’t have gone to better benefits or improved coverage for Medicare beneficiaries, so getting savings by calling off implementation is likely to mean beneficiaries overall are better off.” She said that with the loss of drug rebate revenue under Trump’s regulation, “Part D plans were expected to raise their premiums, leading to increased premium subsidies paid by the federal government, resulting in greater overall costs for the Medicare program as well as higher drug plan premiums paid by enrollees.”

The more substantive question concerns the impact of the policy and what it would do for drug innovation. CBO’s thinking on the issue has evolved over the years, while Democrats’s proposals have increasingly been downsized.

CBO estimated that the drug pricing provisions in the Build Back Better Act passed in the House will have a very modest impact on the number of new drugs coming to market in the U.S. over the next 30 years. Only one fewer drug in the 2022-2031 period would be created, CBO said, then four in the next decade and 5 in the decade after that. For context, that’s out of 1,300 drugs, or a reduction of 0.8 percent, Cubanski said.

Still, if drug prices are cut because of government pressure, then there will be an impact. To a large extent, the impact is unknowable. Health plans currently steer enrollees to their preferred medications, but the drug manufacturing market may adapt in ways not yet understood.

Anuzis pointed to a 2021 University of Chicago paper that predicts a much larger impact from the Build Back Better drug policy. The paper, whose lead author is Tomas J. Philipson, former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under Trump, calculated 139 fewer new drugs through 2039, a rate 27 times higher than CBO. He told the Fact Checker it’s unclear why the estimates are so different because CBO does not provide enough information to replicate its work.

CBO officials counter that they have incorporated feedback on their model from many experts, including Philipson, and published a working paper that explained their reasoning, based on perspectives from a range of policy experts. CBO’s goal is have an estimate that falls in the middle of a distribution of outcomes. While CBO has sometimes published the code to its models, such as in the tax area, officials said it is not practical to do so with every issue and still have the agency focus on its main job — providing analysis and information to lawmakers.

We are obviously not in a position to adjudicate the differences. In any case, we can hardly fault Manchin for relying on CBO, a nonpartisan organization whose forecasts often help shape legislation.

The ad “is blatantly lying about Senator Manchin’s record,” said Sam Runyon, Manchin’s communications director. “West Virginia seniors know Senator Manchin has worked tirelessly to protect Medicare and reduce prescription drug costs.”

The Pinocchio Test

The 60 Plus ad is certainly pushing the envelope. While technically the Build Back Better plan would reduce Medicare spending by $300 billion over ten years, it’s false to suggest that this means cuts to beneficiaries and programs. About half of the amount is simply a book-keeping maneuver.

As for the core policy question, no one really can predict the possible impact from government drug negotiation. CBO predicts some fewer drug approvals, but only on the margins. 60 Plus relies on a more pessimistic forecast.

But given the dispute in the academic community, 60 Plus cannot reasonably assert that the result will be “even fewer treatments and cures.” It’s especially strange that 60 Plus relies on CBO’s forecast of $300 billion deficit reduction — but then ignores its more positive report on drug innovation in the same report.

60 Plus earns Three Pinocchios. The legitimate debate over the potential impact of this policy just barely kept this from being a Four-Pinocchio ad.

Three Pinocchios

Send us facts to check by filling out this form

Sign up for The Fact Checker weekly newsletter

The Fact Checker is a verified signatory to the International Fact-Checking Network code of principles