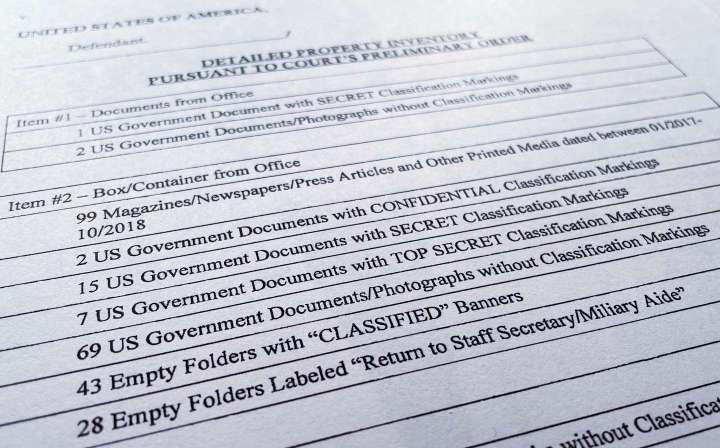

We received yet more details Friday on the FBI’s search of Mar-a-Lago. One immediately stood out: According to the newly released inventory list, agents seized 48 folders bearing classified banners but which were nonetheless empty.

What we know about Trump and the empty folders

The new detail is tantalizing for a host of reasons, including that the separation of classified documents from their folders is something the National Archives has previously described as being “of most significant concern.”

We know very little about what this means right now, though, and experts say it doesn’t necessarily mean the documents are missing, as some Trump critics theorized. What it does seem to reinforce is how sloppily classified information was handled.

In both the search warrant affidavit released last week and a Justice Department filing in a court case this week, the government has pointed to a February referral from the National Archives. The referral raised concerns about Trump’s potential mishandling of sensitive documents and urged an investigation.

“Of most significant concern was that highly classified records were unfoldered, intermixed with other records, and otherwise unproperly [sic] identified,” the National Archives said.

The biggest question is obviously: Why were those folders empty? Since classified documents were previously returned “unfoldered” — and others were recovered in the search last month — and now we have classified-marked folders without documents in them, it’s possible they match up.

Whether they actually do match is another matter, as is whether the documents can even be traced to a given folder.

David Priess, a former CIA officer whose work there included delivering the President’s Daily Brief, said Friday that the presence of empty folders doesn’t mean documents are missing, but also that it’s possible we won’t know for sure. He said the folders could contain markings allowing them to be traced to specific documents (but that’s not certain), or that they could be connected using forensic techniques.

“We cannot rule out that those empty folders contained classified documents that were not discovered in the search and seizure,” he said. “We just don’t know. That’s much harder to determine.”

He also noted it was possible that the folders were separated from the documents when they were still in the White House, before they were taken to Mar-a-Lago.

But mostly, he said, it’s further evidence of something we already knew: The documents were haphazardly stored.

Classified documents aren’t always kept in folders denoting the documents’ classification. But the Defense Department’s manual states in a section on information security:

Classified files, folders, and similar groups of documents shall have clear classification markings on the outside of the folder or holder. Attaching the appropriate classified document cover sheet (Standard Form (SF) 703, “Top Secret (Cover sheet);” SF 704, “Secret (Cover sheet);” or SF 705 “Confidential (Cover sheet)”) to the front of the folder or holder shall satisfy this requirement. These cover sheets need not be attached when the item is in secure storage (e.g., GSA-approved security container).

The photo of items seized that was released by the Justice Department this week didn’t show anything that outwardly appeared to be a folder, but it did show the cover sheets with classification markings.

Of obvious concern to the National Archives is what this says about how the records were treated and whether they’ve all been recovered. Not only were these documents commingled with other papers, including more personal ones, and not properly identified, they were also apparently separated from their folders in large numbers — larger than we knew before. A big reason officials worry about mixing classified documents with nonclassified documents is the possibility they will be lost.

NARA declined to comment, citing the ongoing DOJ investigation.

The numbers of documents seized from each item also, notably, doesn’t match up with the number of empty folders. In Item No. 2 — a “box/container” in Trump’s office — there were 43 empty folders with classified banners but only 24 documents containing classification levels between “confidential” and “top secret.” And Item No. 33 — a box/container from the storage room — contained two empty folders with classified banners but no actual classified documents.

Also worth emphasizing is something else contained in the Justice Department’s filing this week.

We’ve known for a while, through reporting by The Washington Post and others, that Trump’s document-retention habits left a lot to be desired. He often ripped up documents or even threw them in the toilet. The Justice Department filing says NARA cited the former as a particularly pressing concern.

“The NARA Referral was made on two bases: evidence that classified records had been stored at the Premises until mid-January 2022, and evidence that certain pages of Presidential records had been torn up,” it said. “Related to the second concern, the NARA Referral included a citation to 18 U.S.C. § 2071.” (That statute deals with the “concealment, removal, or mutilation” of government items.)

It’s not clear whether NARA’s citation of that statute relates to the documents received in January 2022 or at the end of the Trump administration, when NARA publicly confirmed it received documents that had been torn up. (The filing also doesn’t say whether there was any evidence Trump did this with actual classified documents, specifically.)

But the Justice Department opted to include that detail in a full-throated filing, obviously intended to speak to the state of its investigation. And now there are some empty folders that only add to the many questions that surround all of this.