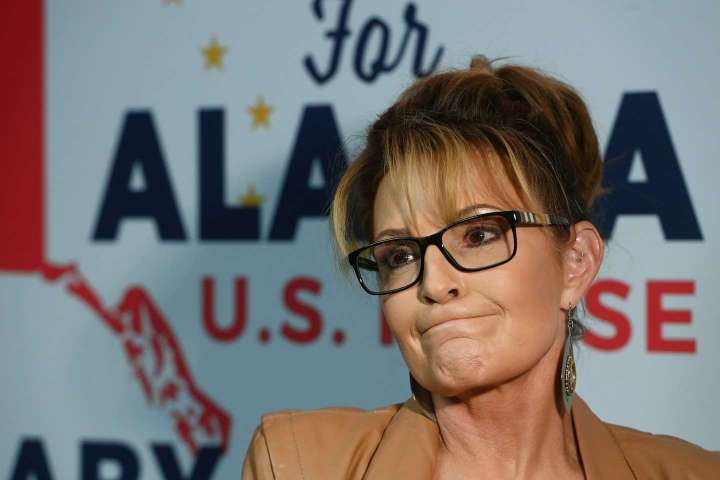

Sarah Palin has made no secret since her loss in the Alaska special congressional election last week that she doesn’t appreciate the state’s new ranked-choice voting system, which she and other prominent conservatives have blamed for her loss.

It’s official: Sarah Palin cost the GOP a House seat

The state Division of Elections has put out new data on how the election went down. And the data suggest that the other Republican in the race, Nick Begich, would have defeated Rep.-elect Mary Peltola (D) if the race had boiled down to the two of them.

Under the state’s system, Begich was eliminated when he finished in third place. That meant his voters who ranked the remaining two candidates below Begich saw their votes distributed to their second choice. Palin won about half of those voters, while Peltola won 28 percent of them (with the rest not ranking either of them). But it wasn’t enough: Peltola led by enough on first-choice votes that she defeated Palin by about three points.

In doing so, a Democrat won a seat that had gone for Donald Trump by 10 points in the 2020 election.

Begich, it appears, would not have suffered the same fate in a scenario in which Palin had been eliminated instead. According to a review by FairVote, 59 percent of Palin’s voters would have gone to Begich, while just 6 percent would’ve gone to Peltola — far less than the 28 percent of Begich-first voters who crossed the aisle.

Given Peltola took about 40 percent of first-choice voters and Begich took about 28 percent, that would mean Begich would have surpassed her with relative ease once the second-choice ballots were counted. He would have won by about five points, compared with Palin’s three-point loss.

There are some caveats, including that some voters might have adjusted their votes if polls suggested Begich, rather than Palin, was the favorite to make the final two. But Begich’s five-point margin — and the fact that he would’ve overtaken Peltola even though he trailed by more than Palin among first-choice voters — is very instructive. We’re also dealing with a situation in which we’re divvying up more Palin voters than would have existed had she finished third. But the fact that so few Palin-first voters ranked Peltola ahead of Begich also suggests that virtually any drop-off by Palin would accrue to Begich’s benefit. He was obviously the more broadly acceptable candidate; it was only a matter of how superior he was to Palin on that front and whether it would have been enough.

And importantly, that five-point margin would have been in line with other recent special elections, in which Republicans have generally underperformed the 2020 election results by a handful of points. But with Palin in the final two, the GOP did worse than in any other recent special election, relative to 2020.

Palin responded to her loss like you might expect: blaming lots of factors besides the candidate who actually lost the head-to-head. She decried ranked-choice voting, which she labeled a “newfangled, cockamamie system.” She even went so far as to urge Begich to drop out of the November general election (which features the same system and same three candidates), reasoning that she finished ahead of him on first-choice votes and that he would just “split” the vote again.

That, of course, isn’t really how ranked-choice voting works. People are welcome to choose whomever they want as their first choice, but they can still have their votes counted if that candidate doesn’t make the final two by ranking others they’d like to see win, in order.

Palin, of course, has never been terribly interested in such pragmatism. She also expressly suggested her supporters shouldn’t bother with ranking Begich and even toyed with the idea of ranking Peltola second on her ballot.

It’s not clear how much that advice actually penetrated. But it’s fair to deduce that, on top of Palin’s well-demonstrated divisiveness, it didn’t help. If you declare Begich wasn’t worthy of being your voters’ second choice, you can’t really complain when Begich voters decide that same thing about you.

The question for Palin’s party now is how it responds to this new data. Despite Palin’s claims that Begich should drop out, he can now credibly claim Palin is the one who truly jeopardizes this seat. “I would’ve won!” is a pretty strong message, and the gap between the two of them in first-choice votes — Palin led by about three points, 31 percent to 28 percent — is small enough that Begich needn’t gain too much to overtake Palin and make the final matchup with Peltola.

Palin, of course, only lost to Peltola by three points, and the general election could be more favorable to the GOP. So anybody with designs on getting her out of the race shouldn’t hold their breath. But it’s pretty obvious that if she sticks it out, she just might risk costing the GOP a seat — again.