Donald Trump called into Hugh Hewitt’s radio show Thursday to chat (in his characteristic style) about how the world was arrayed against him and how he nonetheless managed to triumph.

‘The files were declassified’ is a political argument, not a legal one

But it is useful to consider the context in which that comment came. Hewitt had asked whether Trump expected to be indicted immediately after he cleared the runway for Trump to wave away questions about the material the FBI seized in their search of his Mar-a-Lago facility last month.

A former aide, Kash Patel, has said that Trump declassified that material, Hewitt prompted. Did Trump remember doing so?

He did. What’s more, Trump added: “I have the absolute right to declassify, absolute. A president has that absolute right, and a lot of people aren’t even challenging that anymore.”

Hewitt then asked about possible indictment.

This claim, too, is familiar to anyone paying attention to Trump. Since the search became public, the presence of material marked as classified has been fodder for political commentary. But in insisting that he declassified it, Trump’s making a political claim, not a legal one. And he’s making a political claim, in part, to stoke precisely the sort of anger that he understands would erupt if he was indicted.

In the search warrant it obtained to retrieve material from Trump, the Justice Department delineated three statutes that it believed had been violated: 18 U.S. Code 793, 1519 and 2071. As has been noted in the past, at no point in any of the three does the word “classified” appear. What is alleged, it seems, is not that Trump had classified material but that he was in possession of material that was property of the government. The Presidential Records Act establishes that the product of Trump’s time as president is generally not his, but the office’s. His decision to bring it with him is, by itself, a potential violation.

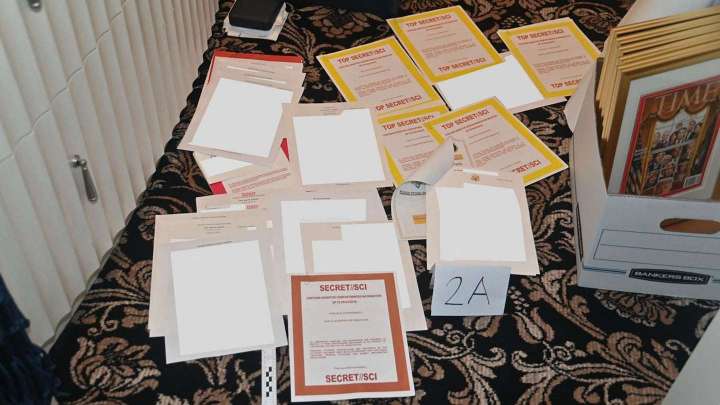

Nonetheless, people are generally more familiar with the prohibitions surrounding classified information than they are documents that are slotted into not-classified-but-not-privately-owned ones. So reports that classified material was seized — and of course, that infamous photo of documents with classification markings splayed across the Mar-a-Lago carpet — spurred a lot of tittering about what Trump had and why.

It’s to combat that theorizing that Trump and his allies have been so fervent about trying to claim that he declassified everything. When news reports emerged this year that documents with classification markings had been turned over by the former president, Patel first made the assertion that all of it had been deemed fit for public consumption (and apparently, private storage). Patel later qualified this, noting that Trump’s blanket order ended up being watered down by opposition from the intelligence community (and though Patel didn’t say this, Trump himself did).

Then the Mar-a-Lago search happened. Trump and his allies insisted that bulk declassification had occurred, though it’s not clear that anyone necessarily knew which things were included in his stash. Did he declassify just those things on his way out the door? Did he declassify nearly everything and take some subset with him? Did he have a standing order that things he grabbed became declassified, as he claimed? (A number of former administration officials expressed no familiarity with such a system.)

There are two interesting qualifiers to this whole line of argument.

The first, as The Washington Post’s Aaron Blake has pointed out, is that Trump’s lawyers have not claimed in legal filings that the material was declassified. This might be attributed to the point that such a claim is largely irrelevant to the legal question, as indicated above. But the lawyers have not been shy about invoking a number of other claims about what Trump did, so the disinclination to elevate this particular claim is noteworthy. After all, there are very different ramifications between Patel making an unsupported claim to Breitbart and an attorney making an unsupported claim in a legal filing.

The other qualifier is perhaps the more important one. This week, a less-redacted version of the affidavit used to obtain the search warrant was revealed, giving us a better sense of what the government was seeking. It adds new context to the weeks before the search — and in particular, a moment in June in which Trump’s team claimed that it had turned over all material with classified markings.

This is important. After learning that the boxes of documents Trump sent back to Washington in January were incomplete, the Justice Department subpoenaed “[a]ny and all documents or writings in the custody or control of Donald J. Trump and/or the Office of Donald J. Trump bearing classification markings.” Not “classified material.” Material “bearing classification markings.” So even if the Secret/SCI document prominently featured in the Mar-a-Lago photo was, in fact, declassified, Trump should not have had it after receiving the subpoena.

After all, in June, Justice Department officials had met with Trump’s team and received a packet of classified material that was still in Trump’s possession. Critically, Trump’s lawyers then asserted that no more “responsive” material was present at Mar-a-Lago — that is, no more material that met the stipulations of the subpoena.

At another point in the affidavit, the government notes that “When producing the documents, neither FPOTUS COUNSEL 1 nor INDIVIDUAL 2″ — Trump attorney Christina Bobb — “asserted that FPOTUS had declassified the documents.” (In a footnote, it adds that classification status is irrelevant to the statutes at issue anyway.)

Again, then, the question of classification status is, for legal purposes, irrelevant. It seems likely that 18 U.S. Code 1519 was cited because it applies to anyone who “makes a false entry in any record, document, or tangible object with the intent to impede, obstruct, or influence [an] investigation” — perhaps covering the scenario illustrated above. By focusing on classification, then, Trump’s trying to win over the public and not the judge.

Why? Because Trump prefers to move every fight to the public square, where his base of support is vocal and intimidating. He understands that he can use his supporters’ anger to influence the decisions being made by elected officials and government actors. Attorney General Merrick Garland is just as aware of the likely response to a Trump indictment as is Trump.

Put simply then: Arguing that he declassified the seized documents isn’t going to bolster his defense if he’s indicted. But arguing that he’s being railroaded because the government refuses to acknowledge that the documents were declassified? That might help keep him from being indicted in the first place.