The Justice Department asked a federal appeals court Friday night to override parts of a judge’s order appointing a special master to review documents seized from former president Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home and club, arguing that some of the terms hamper a critical national security investigation.

Justice Dept. appeals judge’s rulings on classified material in Mar-a-Lago case

The new filing from the Justice Department notes that it disagrees with that decision but for the time being is asking the appeals court to intercede on two parts of Cannon’s ruling — one barring criminal investigators from using the seized material while the special master does his work, and another allowing the special master to review the roughly 100 classified documents seized as well as the nonclassified material.

The government filing asks for a stay of “only the portions of the order causing the most serious and immediate harm to the government and the public,” calling the scope of their request “modest but critically important.”

It’s unclear how long the special master review, or the appeals, might take, but the new filing asks the appeals court to rule on their request for a stay “as soon as practicable.”

Cannon ordered Dearie to complete his review by Nov. 30. She said he should prioritize sorting through the classified documents, though she did not provide a timeline as to when that portion must be completed.

The Justice Department had asked in a previous court filing for the review to be completed by Oct. 17. And Trump’s lawyers had said a special master would need 90 days to complete a review.

Dearie, 78, was nominated to the bench by President Ronald Reagan (R) after serving as a U.S. attorney. Fellow lawyers and colleagues in Brooklyn federal court describe him as an exemplary jurist who is well suited to the job of special master, having previously served on the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which oversees sensitive national security cases.

The appeals court filing also argues that the very premise of Cannon’s order, as it relates to the classified material, makes little sense because classified documents are by definition the property of the government, not a former president or a private club.

Trump “has no claim for the return of those records, which belong to the government and were seized in a court-authorized search. The records are not subject to any possible claim of personal attorney-client privilege,” prosecutors wrote, adding that Trump has cited no legal authority “suggesting that a former President could successfully invoke executive privilege to prevent the Executive Branch from reviewing its own records.”

The Justice Department contends that Cannon’s instruction for intelligence officials to continue their risk assessment of the Mar-a-Lago case, while criminal investigators could not use that same material in their work, is highly impractical because the two tasks are “inextricably intertwined.”

That order “hamstrings that investigation and places the FBI and Department of Justice (DOJ) under a Damoclean threat of contempt should the court later disagree with how investigators disaggregated their previously integrated criminal-investigative and national-security activities,” the filing argues. “It also irreparably harms the government by enjoining critical steps of an ongoing criminal investigation and needlessly compelling disclosure of highly sensitive records, including to” Trump’s lawyers.

Prosecutors have also said the judge’s restriction on further investigation prevents them from determining if any other classified documents remain to be found — a potential ongoing national security risk — and the appeals filing says it also makes it harder for the FBI to determine if anyone accessed the documents they did recover.

“The court’s injunction restricts the FBI … from using the seized records in its criminal-investigative tools to assess which, if any, records were in fact disclosed, to whom, and in what circumstances,” the new filing says.

Similar arguments did not sway Cannon, who repeatedly expressed skepticism about the Justice Department claims, even on the question of whether the roughly 100 documents at the core of the case were classified. In her ruling Thursday, she rejected the argument that her decision will cause serious harm to the national security investigation. Evenhanded application of legal rules “does not demand unquestioning trust in the determinations of the Department of Justice,” the judge wrote.

Cannon, a Trump appointee confirmed by the U.S. Senate just days after Trump lost his bid for reelection, added that she still “firmly” believes that the appointment of a special master, and a temporary injunction against the Justice Department using the documents, is in keeping “with the need to ensure at least the appearance of fairness and integrity under unprecedented circumstances.”

The Justice Department is investigating Trump and his advisers for possible mishandling of classified information, as well as hiding or destroying government records — a saga that began last year when the National Archives and Records Administration became concerned that some items and documents that were presidential records, and therefore government property, were instead in Trump’s possession at his Florida club.

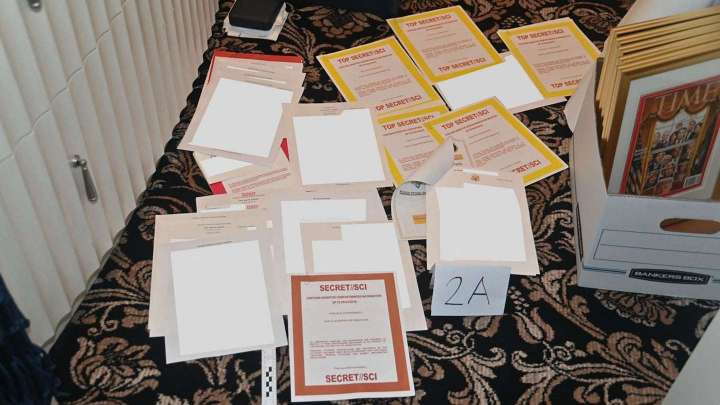

After months of discussions, Trump aides turned over about 15 boxes of material to the archives, and a review of those boxes turned up what officials say were 184 documents with classification markings, including some that were top secret.

After the FBI and Justice Department opened a criminal investigation, a subpoena was sent in May seeking the return of all documents marked classified. In response, a lawyer for Trump turned over 38 additional classified documents, and another Trump aide signed a document claiming they had conducted a diligent search for any remaining sensitive documents, prosecutors said.

“The FBI uncovered evidence that the response to the grand-jury subpoena was incomplete, that classified documents likely remained at Mar-a-Lago, and that efforts had likely been undertaken to obstruct the investigation,” the filing says in describing the decision to get a court order to search Mar-a-Lago.

That search, officials said, turned up roughly 100 more classified documents, including some that were at the highest level of classification.

Two weeks after that search, Trump’s lawyers filed court papers seeking the appointment of a special master to review the seized material and hold aside any documents covered by attorney-client privilege or executive privilege.

Executive privilege is a loosely defined legal concept meant to safeguard the privacy of presidential communications from other branches of government, but in this case Trump’s legal team has suggested the former president can invoke it against the current executive branch.

The government’s appeals argument also tries to demolish the suggestion that Trump may have declassified the material while he was president, noting that his legal team has never claimed he did so at any point in the long months of negotiating the return of the documents, and since the raid has only suggested he might have or could have declassified them.

In buying that reasoning, Judge Cannon “erred in granting extraordinary relief based on unsubstantiated possibilities,” the Justice Department lawyers wrote.