Available on: Xbox Series X and Series S, PC

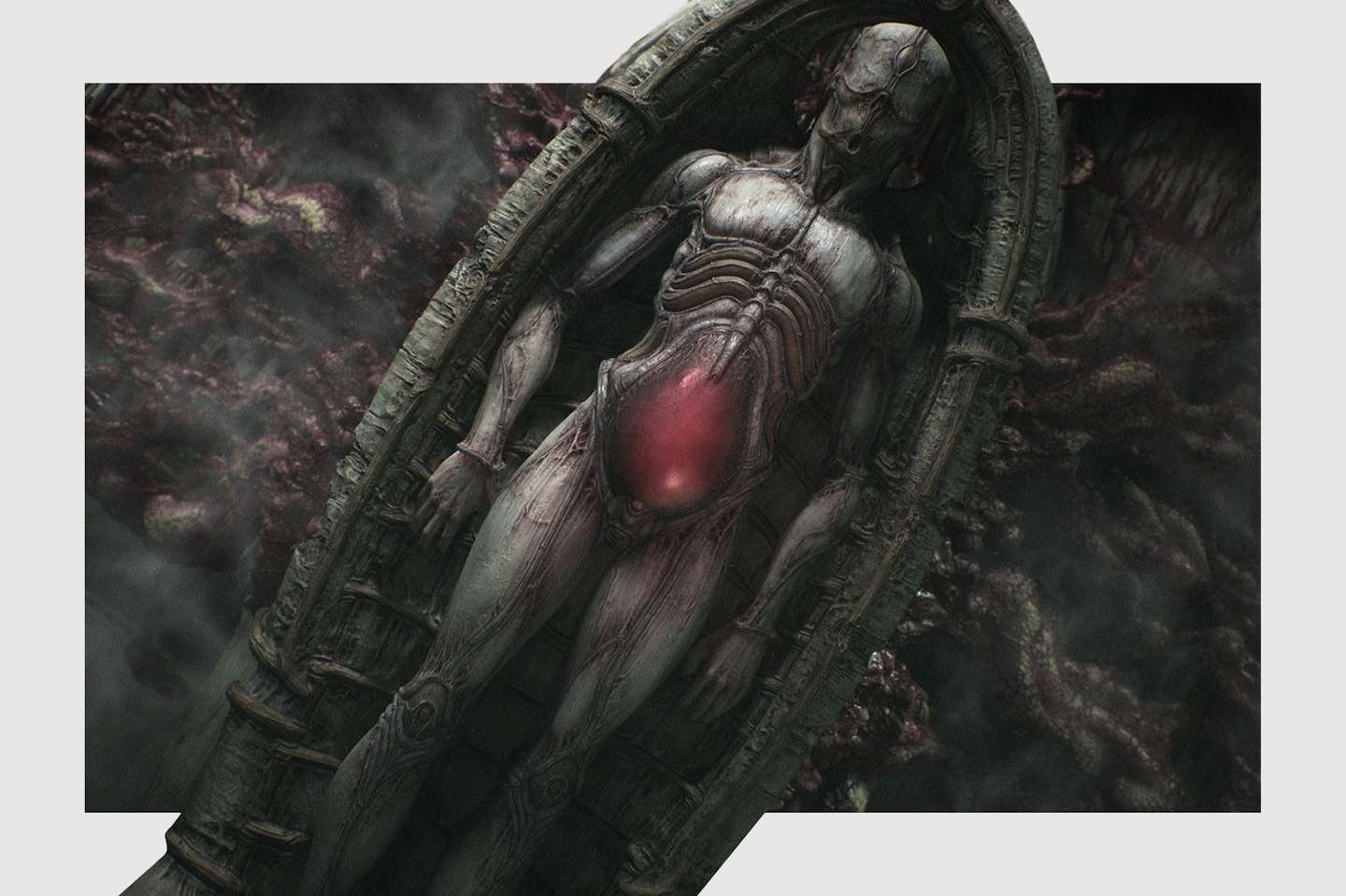

‘Scorn’ is a horror game more faithful to H.R. Giger than ‘Alien’

But Alien was never really about Giger’s work. In fact, the film’s most prominent themes are anything but alien: average laborers made to suffer for the unquenchable greed of megacorporations, fear of the unknown, the moral obligations of science and motherhood (Ripley and the Alien Queen are both, after all, mothers). These mundanely human topics are what made “Alien” such a groundbreaking sci-fi film when it was released in 1979. In a genre that was traditionally viewed from the lofty perspective of a Starfleet officer or a Jedi Knight, Alien was about truckers in space.

“Scorn,” a first-person horror game from Serbian developer Ebb Software and published by Kepler Interactive, is most definitely not about truckers in space. As I explored the nightmarish world of “Scorn,” I felt like I was walking through a gallery of Giger’s paintings with minimal loss in translation. It was a bizarre and sometimes breathtaking title. But some of the clumsy map design, phoned in combat mechanics and an especially intense set piece during the game’s final act made me wish for a more focused, shorter journey — and even a more prominent trigger warning.

On “Scorn’s” Kickstarter page, Ebb described the concept behind the game as “being thrown into the world.” (This is likely a reference to German philosopher Martin Heidegger, who wrote about exactly that; “Scorn’s” original title was “Dasein,” after Heidegger’s existential concept of being.) You play as a hairless humanoid waking up in a grotesque but beautifully realized biomechanical world. Walls that look like taut sinew are girded with beams and rafters reminiscent of bones. Flaps of flaky, skinlike cloth hang in tatters from ceilings. Decrepit, skeletal machines are powered by gunmetal intestinal tracts, and controlled by consoles rippling with industrial blood vessels. The bleak landscapes and towering, imposing buildings are clearly a nod to the Polish artist Zdzislaw Beksiński. Even the dust particles drifting in the smoky, dull light of eye-shaped lamps move in a way that feels unnatural.

Your character enters “Scorn” naked and ignorant, and as the player, you are no better off. The game sports a bare-bones UI that disappears when you’re out of combat, and none of the creatures you encounter nor places you visit have names in-game. There is no dialogue, quest log, inventory or map. There are no obvious objectives to complete or goals to reach. The only thing you can do is move forward — in true existential fashion, because you can. The many puzzles you’ll encounter can only be solved through trial and error. This minimalist approach is how “Scorn” delivers on its concept of “being thrown into the world.”

Without notes or quest givers, I had to experiment my way through the game. As someone who sucks at puzzles, “Scorn” was my Dark Souls. The puzzles in “Scorn” are hard and many of them had me cursing at my monitor, wishing for walk-throughs that didn’t exist yet. However, when I did eventually figure out the really tough puzzles, I got a cool sense of satisfaction. The solutions feel earned; they require you to be very observant and tinker with everything. Be prepared to travel back and forth a lot between areas, because sometimes a switch you pull will activate something somewhere else.

Unfortunately, navigating “Scorn” was also a real hassle. Eschewing a minimap is a perfectly respectable design decision, but it doesn’t work when everything looks the same. For all of “Scorn’s” exquisite detail, there are several areas that look way too similar, which made it very easy to get lost as I was backtracking to solve puzzles. There’s one specific hub in the game’s third act that requires you to extend a passageway to four different tunnels. You have to travel through all four multiple times, and with no visual cues to tell them apart, I spend half my time in that section wandering aimlessly.

“Scorn’s” combat is designed to be a struggle. You are a desperate survivor, not a soldier. The nameless machine-flesh weapons that the player character grafts onto their body resemble a pneumatic hammer, a shotgun, an even bigger shotgun and a grenade launcher. These weapons aren’t very effective, reloading is slow and ammunition is scarce, leading to some unwieldy but tense fights. If you die, you’ll be punished by “Scorn’s” unforgiving checkpoint system and forced to retread a significant amount of gameplay, unable to skip any of the game’s lengthy puzzle animations. Once, the game crashed on me during a cutscene, costing me nearly an hour of progress. (Kepler told reviewers that a day one patch will address these bugs.)

I understand what Ebb was going for and I appreciate feeling like the player character is entirely out of their element. For most of the game, it’s even enjoyable. But it all culminated in an underwhelming boss fight that boiled down to me circle strafing around the big bad guy for five minutes until an opening appeared for me to get a single shot in. I had to repeat this six times. It was the sort of monotonous, artificial difficulty that took the game from being scary to feeling like a chore.

“Scorn’s” gameplay trailers have properly portrayed it as a gory affair. Expect to see lots of guts being splattered and blood being spilled as your player character guns hostile abominations and sacrifices innocent beings to unlock new areas. Toward the end of the game, there are also lots of risque statues and landmarks clearly influenced by Giger’s more erotic work. The game’s description on Steam and the Microsoft Store make note of all this.

But there is one gruesome cutscene I can’t describe fully in print. All I can say is that it involves extreme torture, mutilation and what I would argue is a form of sexual assault. The scene is unskippable and happens entirely in first person. I emailed Kepler about this and was sent a content warning screen that will be added to “Scorn” before release, containing the usual disclaimers about epileptic seizures, violence, gore and “sensitive and adult themes.” Maybe I’m overanalyzing how brutal this scene could be for some people, but I don’t think this general warning is enough of a heads up for what I played. Prospective players, be warned.

I finished “Scorn” wishing that there were things it did better, but also hoping that more games could learn from its finer points (unskippable torture scene aside). The combat is mediocre and arguably unnecessary, committing the cardinal “intentionally clunky shooter” sin of forcing a boring busywork boss fight on the player. The world was intriguingly creepy, but also uniform to the point of confusion. Still, I also wish there were more small titles like “Scorn” that play out like one giant level with a clear, cohesive theme. In an age when games are trying to squeeze every possible achievement hunting minute out of us, I loved that “Scorn” had zero collectibles to track down. It kept me immersed in the game’s atmosphere instead of worrying about a trophy I might’ve missed.

“Scorn” is an art house experience. I’m sure that other reviewers will plumb “Scorn” for its hidden high-minded commentary on the human condition, but for me, the appeal of the game is how it made me feel rather than think. I felt a constant, humming anxiety for simply existing in its macabre world. I was never particularly scared of anything I encountered; like the playable creature, I just wanted out.